NCAA Eligibility Center

advertisement

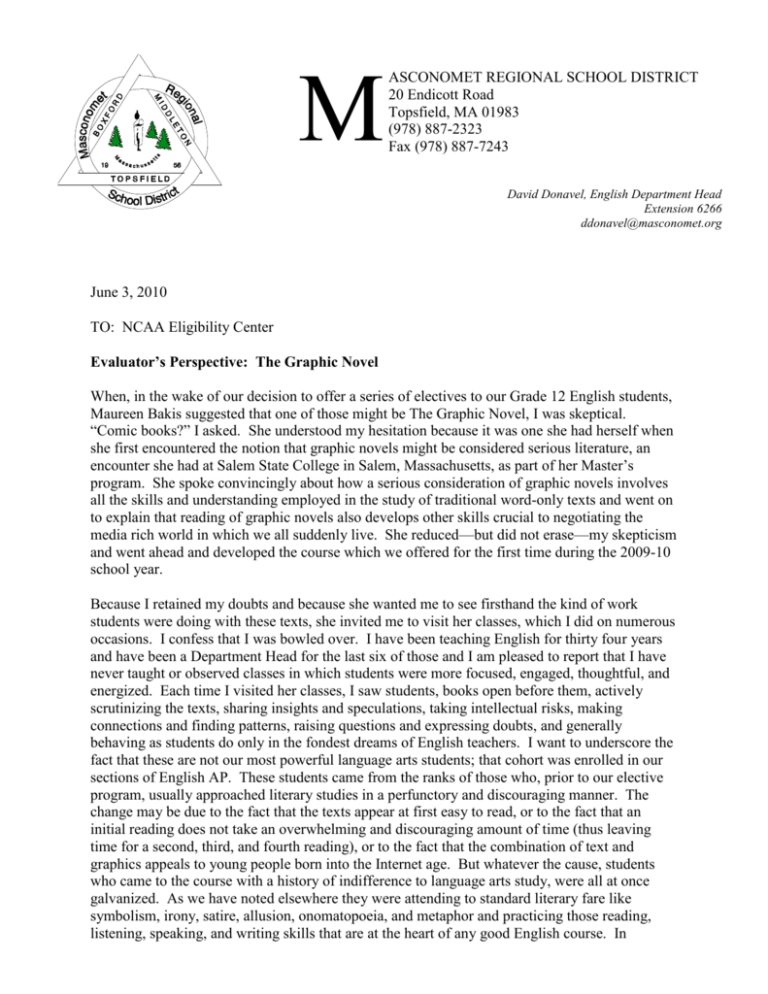

M ASCONOMET REGIONAL SCHOOL DISTRICT 20 Endicott Road Topsfield, MA 01983 (978) 887-2323 Fax (978) 887-7243 David Donavel, English Department Head Extension 6266 ddonavel@masconomet.org June 3, 2010 TO: NCAA Eligibility Center Evaluator’s Perspective: The Graphic Novel When, in the wake of our decision to offer a series of electives to our Grade 12 English students, Maureen Bakis suggested that one of those might be The Graphic Novel, I was skeptical. “Comic books?” I asked. She understood my hesitation because it was one she had herself when she first encountered the notion that graphic novels might be considered serious literature, an encounter she had at Salem State College in Salem, Massachusetts, as part of her Master’s program. She spoke convincingly about how a serious consideration of graphic novels involves all the skills and understanding employed in the study of traditional word-only texts and went on to explain that reading of graphic novels also develops other skills crucial to negotiating the media rich world in which we all suddenly live. She reduced—but did not erase—my skepticism and went ahead and developed the course which we offered for the first time during the 2009-10 school year. Because I retained my doubts and because she wanted me to see firsthand the kind of work students were doing with these texts, she invited me to visit her classes, which I did on numerous occasions. I confess that I was bowled over. I have been teaching English for thirty four years and have been a Department Head for the last six of those and I am pleased to report that I have never taught or observed classes in which students were more focused, engaged, thoughtful, and energized. Each time I visited her classes, I saw students, books open before them, actively scrutinizing the texts, sharing insights and speculations, taking intellectual risks, making connections and finding patterns, raising questions and expressing doubts, and generally behaving as students do only in the fondest dreams of English teachers. I want to underscore the fact that these are not our most powerful language arts students; that cohort was enrolled in our sections of English AP. These students came from the ranks of those who, prior to our elective program, usually approached literary studies in a perfunctory and discouraging manner. The change may be due to the fact that the texts appear at first easy to read, or to the fact that an initial reading does not take an overwhelming and discouraging amount of time (thus leaving time for a second, third, and fourth reading), or to the fact that the combination of text and graphics appeals to young people born into the Internet age. But whatever the cause, students who came to the course with a history of indifference to language arts study, were all at once galvanized. As we have noted elsewhere they were attending to standard literary fare like symbolism, irony, satire, allusion, onomatopoeia, and metaphor and practicing those reading, listening, speaking, and writing skills that are at the heart of any good English course. In addition, they were practicing 21st Century Skills such as “creativity and innovation, critical thinking and problem solving, and communication and collaboration” as well as developing what one might call visual literacy. I must report that my initial skepticism has vanished and that I am well pleased that enrollment in The Graphic Novel has increased by about forty percent for next year. In thinking about the apparent non-traditional nature of this course, I was reminded of some of the courses we offered at Masconomet when I first came to work here. These included the expected such as Composition Workshop and Major British Writers, but we also offered strange items such as Witchcraft and, I believe, Science Fiction. This is not unusual of course. A visit to the course catalog at almost any college—even the staid ivies—reveals the usual mix of traditional and nontraditional titles. It would appear that the central feature of a “real” English course is not so much the texts under study or even the themes around which the courses are centered (Yale University offers “Writing about Food,” “Habits” “Monsters and Monstrosity) but rather the skills that the study encourages. One can practice those skills and acquire the benefits that accrue from language arts study regardless of the content focus of a course and that is why The Graphic Novel at Masconomet is as much a real English course as our English AP or traditional course in American Literature that we require in Grade 11. As we have noted repeatedly, students in The Graphic Novel are not only engaged in practicing standard English language arts skills, they are doing so enthusiastically. It is worth adding that it is no boast to claim that Masconomet is a good school. Our English program is especially strong and year after year students returning from college report that they are better prepared as readers and writers than their peers emerging from other secondary schools, including prep schools. We take our work seriously and would not offer our Grade 12 students anything other than a solid, substantial course in English. Indeed, our decision to offer electives in Grade 12 to replace the “one size fits all” course we ran for decades was driven by our desire to bolster, not weaken, the skills our students take to college. Given what I have observed and all I have heard, there is every reason to think that The Graphic Novel succeeds in this. I urge the NCAA to approve this course. For many of our seniors, The Graphic Novel is perhaps the first time they have been so pleasingly engaged with text, the first time they have discovered that they can read with skill and understanding, speak with clarity and conviction, ask penetrating questions and develop innovative insights. It is for many of them, perhaps, the first time they have discovered the power of their own minds. This is wonderful, gratifying to students and teachers alike and so promising for in this course students are vigorously and rigorously practicing the very skills likely to benefit them as they move on to college. How ironic it would be if this experience, the one that may most handsomely set them up for success in their subsequent education, should be the very one that makes them ineligible for participation in intercollegiate sports. Sincerely, David Donavel