File - Nicole Antkiewicz

advertisement

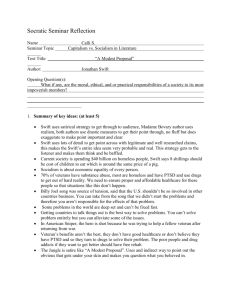

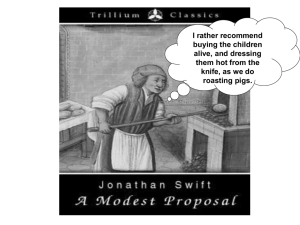

Antkiewicz 1 Nicole Antkiewicz Professor King ENG137H-Section 21 4 October 2013 Babies: A Dime for a Dozen Dictators fear laughter, the proverb says, in some instances even more than firearms. As one of our more popular contemporary comedians, Jon Stewart in The Daily Show illustrates why by parodying conventional news genres and speaking truth to power. Audiences laugh in the hope that Stewart's artfully positioned quips reach their assigned targets, helping to rectify some aspect of alleged social inadequacy. Stewart’s slings and arrows dramatize the role of big money in politics, and take stabs at our apparent wealth and class divide. Pessimistic views fear that the man wields mere slingshots against today’s consumer giants, but it can be argued that satire's weapons—wordplay, irony, caricature—can reap surprisingly strong benefits. While contemporary satire emphasizes social inequality and positions itself against tyranny, past satirists focused more on surprising or shocking their audiences. Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” written during the Irish potato famine of the 1720’s exemplifies this trend. Through emotionally-charged realism and logical economic reasoning, Swift’s persona persuades his audience to take up the eating or selling of the babies of the poor so that the atrocious impact of the famine will be negated. By utilizing his narrative persona’s persuasive power, Swift achieves his goal of mocking those of the upper class for being selfish, while simultaneously attempting to instill a sense of compassion in his fellow countrymen. Swift’s persona chastises the traditional proposals of the wealthy class that have not Antkiewicz 2 worked, and by doing so he primarily establishes himself as one who is trying to implement something with actual plausibility for a positive effect. The audience comes to find that he is like a needle in a haystack, one in a million in the rich class because he actually desires to help the poor out of sheer compassion for his brethren. He targets and attacks the self-interested power, and apathetic nature of the few members of the upper class although he belongs to the EnglishIrish upper-middle class himself. Swift proves that one can reprove and the system one is born into, while still remaining entirely dependent on it. Swift writes out a detailed juxtaposition of what the rich feel is best for the nation, and conversely what Swift feels would be best. The efforts made by the rich (if any were made at all) were largely unsuccessful and because he has “turned [his] thoughts for many years upon this important subject” (para.4) he has garnered the opportunity to “maturely weigh the several schemes of other projectors” (para.4) and find them “grossly mistaken in the computation.” (para,4) Both the speaker and Swift himself feel as though something must be done in the way of social and economic reforms and quickly. That is the central, underlying point of his essay, not to physically eat babies, as he so callously suggests just to get a rouse out of the wealthy. Meanwhile, the speaker offers correct statistical support for his assertions to flesh them out unlike his other rich friends, and gives specific data about the number of children to be sold, their weight and price, and the projected consumption patterns to increase his claim’s persuasive power. Swift calculates numbers as such, “The number of souls in this kingdom being usually reckoned one million and a half, of these I calculate there may be about two hundred thousand couple whose wives are breeders; from which number I subtract thirty thousand couples who are able to maintain their own children” (para. 6). Such economic transactions would better the individual families by providing for them a more established income while alleviating the Antkiewicz 3 effects, Swift seems to suggest. Swift’s persona does this to increase the logical force and statistical correctness of his proposals; Swift does it to critique the economics-above-people philosophy that resulted in the impoverished starving the nation was then facing. The narrative voice’s use of ironic understatement, most evident in his discussion of and repetition of “breed” and “breeders,” dehumanizes the family unit and women themselves. Modeling a calculating rationality that builds Swift’s credibility among some readers, the very same tongue-in-cheek tone encapsulates Swift’s emotional impersonality. Familial and communal ties are destroyed because of the economic downturn of that morbid and brooding time and are further disassembled by the prospect of feasting upon the flesh of the product of a family’s love. Some might argue that reproduction of life through love is the most human aspect of humanity, but this view is compromised by the persona’s readiness to turn the process into an impersonal economic variable by which to calculate supply and demand. By taking such a rhetorical risk with his persona, Swift is underscoring how, even though they have not yet ascertained to do something radical like eat children, the rich are generally unconcerned and heartless in regards to the poor’s economic and social situation. Swift’s authorial persona then retorts negatively in his counterargument, prophesying that family ties will be strengthened, but only in the way of economic, not amorous gain. For example, women will be more careful when pregnant to preserve the possibility of a proper birth and to prevent miscarriages, and men will care more for their wives as if they were merely “mares in foal, their cows in calf, their sows when they are ready to farrow; nor offer to beat or kick them (as is too frequent a practice) for fear of a miscarriage” (para. 26). Just as there is a direct contrast drawn between the speaker’s model and the previous models proposed by the rich, there is a compare and contrast element to the heartbreakingly dramatic imagery brought forth Antkiewicz 4 with the begging women with their children on the dusty streets, in comparison to steaming, roasting baby carcasses being placed on a wooden table in front of an open fire. His overall conclusion is that the implementation of his project will do more to solve Ireland's complex social, political, and economic problems more so than any other measure that has been previously proposed. Swift renders the proposals of the upper classes to be absurd, and he wastes no time in equating his radical proposal to those of theirs. He wants them to see and feel revolted as though they have been suggesting something just as appalling as roasting babies by placing them in the audience’s shoes instead of the proposer’s shoes for once. The rich’s proposals and Swift’s proposal may have not had the same implications, but each has detrimental effects on the mentalities of the lower classes. Throughout the essay, Swift’s narrative persona deftly balances the logical force of statistics against emotional dehumanization. Readers are unsure of whether to trust the writer or not. What finally tilts the balance against the narrator is his complete separation from any of the ramifications of the policies that he proposes. Swift relies on other trusted friends’ advice on the subject matter of Irish famine and the social class divide, and as to what pains should be taken to assuage particular complications—proving that Swift himself is unknowledgeable. He is “assured by” (para. 7) his merchants, and “assured by a very knowing American” (para. 9) of his acquaintance in London. In fact, one could go so far as to say he is almost unqualified to speak on such a matter since he has no children to offer and could not possibly understand the feeling of sacrificing one for the economic and moral “bettering” of society. His wife is also above child-bearing age, so she would not be put into danger. This inadequacy to speak on behalf of the subject fuels his ironic, nonsensical voice, and also adds to his satiric tone. While the credibility of Swift’s speaker is downgraded, Swift’s believability to his audience increases sharply. Antkiewicz 5 The combination of statistical evidence, emotionally infused, yet archaic diction, and the reliance on friends’ advice casts a foolish light on Swift’s persona as a rhetor. The essay’s narrator has an overly factual and desensitizing rhetoric that casts him as a questionable rhetor— at least until his true distance from the situation at hand is revealed. At which point, the majority of the audience finally gets the joke of the essay: he’s got no credibility at all, and neither do those other egocentric wealthy men he so harshly spoke out against! Honestly, satire’s goal—to acquire a target, to speak out against it, and to use wit and humor to ultimately make a change— hasn’t changed all that much through the course of the centuries, as modern satirists still echo the same message by Jon Stewart: “I've always run by the hierarchy of ‘If not funny, interesting.’” Still care for a freshly cooked baby, anyone? Works Cited: 1. Swift, Jonathan. "Jonathan Swift - A Modest Proposal." Jonathan Swift - A Modest Proposal. N.p., n.d. Web. 01 Oct. 2013. Antkiewicz 6 2. Association, American Anthropological. "Jon Stewart Returns to The Daily Show -- Why Satire Matters." The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 05 Sept. 2013. Web. 01 Oct. 2013.