TESTING-GRADING - Tennessee State University

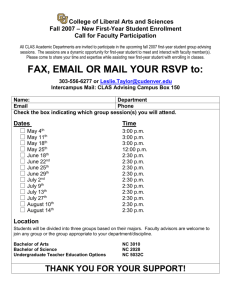

advertisement