DOCX file - Department of Communication Studies

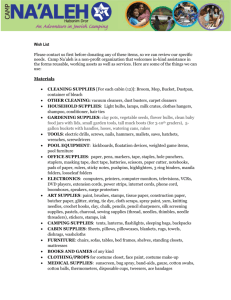

advertisement