Sample Poetry Research 2013

advertisement

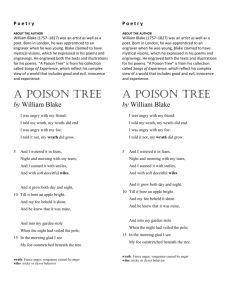

Tang 1 Hailey Tang AP Lit Mr. Sabel 12 November 2013 Anger Towards a Drunk Soldier With the outbreak of the American and French Revolutions, the United States and Europe were both launched into periods housing political dissent. However, this conflict between past conservative ideology and the new, liberal ideas yielded changes in art, marking the start of the Romantic period (Melani). William Blake reveals the cultural and historical influences of this Romantic Era in the metaphorical poem, "A Poison Tree," that conveys the virulent effects of anger through the depiction of a tree's growth. As indicated by the title, the poem focuses on the development of a representative tree, planted as a tool to encompass the negative emotion pent up inside the speaker. In the bulk of the first stanza, the speaker states his emotions in a straightforward manner, assisted by the parallelism of "I was" and "I told." This initiates the speaker's headstrong attitude. Blake's choice of structure supports the repetition of the pronoun, "I," relating to the Romantic trend of more individualistic literature, dealing with more intimate internal experiences, rather than the didactic, moralistic literature of the previous Neoclassical Era (Essick). The "I," however, also provides directness towards the speaker's attitude, emphasizing the speaker's positions towards two polar opposites: friend and foe. With this antithesis, Blake suggests the harmony between friends and the dissonance between enemies, through the actions of the speaker, who "told [his] wrath," and resolved it with his friend, yet, "told it not" to his foe and the wrath remained. The different outcomes indicate communication as the determining factor for success or failure of a relationship, thus, placing heavy weight on the importance of releasing emotion, instead of holding it in. The original title of the poem, "Christian forbearance," further suggests Blake's original Tang 2 proposal that this restraint, encouraged by Christianity, is a factor of the religion which goes against nature (Whitt). After the title change and the first stanza, Blake more subtly suggests that concealing negative emotion, or acts of forbearance, prompts harmful outcomes. To assert the danger of the speaker's withheld wrath, Blake allocates the formatting of the middle stanzas to nourish the growth of the poison tree. Many of the poem's lines begin with "and," creating an anaphora that serves to convey the continuity in the growth of the tree and therefore, speaker's anger. Serving the same function are the times, "Night & morning," and "day and night," all suggesting that as long as the wrath is inside the speaker, it cultivates without pause. This characteristic of wrath and its lasting effects reveals Blake's connection to poison. Like a poison that fiercely spreads once it contacts a victim, the speaker's wrath also spreads in the same manner as that of a toxin. This connection to poison also relates to Blake's opposition to the Industrial Revolution. The poet fled to the countryside because he claimed this machinery violated the humanity and spiritualism of humans (Lopez). Blake crafts the extended metaphor with dual traits: the poison that plagues the speaker, but also the natural growth of the tree. In contrast to the idea of poison, the tree is a less corrupt symbol and primarily develops in the second stanza. While the poison destroys, the tree grows and signifies an entity of nature. The Romantic Era poets commonly wrote about nature and admired the beauty of Earth's dynamic environment (Kirschen). Blake specifically had common pastoral scenes in his poems and often wrote with appreciation towards the environment (Lopez). With the tree, Blake acknowledges the steady, natural, nurturing process of growing a plant, but ironically, the tree is actually the speaker's wrath—not an aspect of Earth's beauty at all. However, the appearance of nature more gently allows the poem to create a deeper, hidden level of the wrath's danger. "Fears" and "tears" support the trees," fears" representing the unease the speaker has and "tears" symbolizing sadness and emotional instability. Both Tang 3 of these aspects indicate the speaker's internal weakness, which the wrath feeds on and grows from. The growth of anger, then, is revealed to be a building effect of destructive emotion. Kept from the foe, the wrath is also implied to be misleading because it is "sunned" with "smiles," but also with "soft deceitful wiles." Therefore, the anger is concealed with the speaker's outward happiness and "smiles," but there is still underlying, quiet deception of the "wiles." This deception provides a darker side to the wrath and a desire to take on a conniving character. Analyst Robert Mikkelsen implied that this reflects Blake's opinion that "incinserity... [spreads] contagion" (Whitt). The wrath, as described with the metaphorical tree develops many layers of negative emotions, hidden by an outward perception of cheer. The speakers wrath, as it broadens into a larger tree, bears an apple in the third stanza, narrowing the anger into a more pointed, but also more exposed form. The alliteration of the "b" sound in the third stanza describes growth of the tree "both" times of day, until it "bore" a "bright" apple, eventually leading up to the point where the speaker's foe "beheld" the apple. These words are then set apart from the rest of those in stanza three, steadily developing the appearance of the apple and changing the state of the apple. As the apple gradually develops, unlike the tree, it is visible and exposed to the open environment. Therefore, the apple is presented as a point of weakness for the speaker and a point of attack for his foe. Literary critics have suggested that this apple is an allusion to the "fruit of deceit" and that the poem could be interpreted as a twisted "counter-myth" to "expose Original Sin as fraud" (Whitt). In the end, Blake proposes that containment of emotions cannot last and an inevitable release will eventually occur. Blake, moving into the poem's ending, depicts the foe's eagerness to take advantage of the speaker. A tone shift appears in the last two lines by the speaker's transition from a cautious to a pleased tone. The enemy "stole" into the speaker's garden, the speaker seems reluctant to Tang 4 acknowledge the possible outcomes. The "night" that "veiled the pole," the pole referring to the trunk of the tree, also creates an ominous setting of darkness, initially suggesting a dreary outcome. When the tone shift occurs, relief accompanies the speaker's new attitude when he sees his "foe outstretched" and dead. This poem is suggested to have correlated with an event in Blake's life, evident by a recorded court trial where Blake was acquitted. Blake supposedly encountered a drunk soldier who intruded into his private garden. After finding this man, invading a sacred place to Blake, the poet drove out the trespasser in rage (Lopez). Therefore, the poem ultimately conveys Blake's own anger towards an infiltrator and the satisfaction of expelling the drunkard from the property. Tang 5 Works Cited Blake, William. "A Poison Tree." Poetry Foundation. Harriet Monroe Poetry Institute. N.d. Web. 30 Oct. 2013. Essick, Robert N. "Blake, William." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 2010: 1-17. Biography Reference Center. Ebsco Host. Web. 5 Nov. 2013. Kirschen, Robert M. "British Romanticism." University of Nevada, Las Vegas. University of Nevada. N.d. Web. 5 Nov. 2013. López Gil, David. "'A Poison Tree,' Social and religious hypocrisy as an unstoppable plague." University of Valencia. David López Gil. 2008. Web. 10 Nov. 2013. Melani, Lilia. "Romanticism." Academic Brooklyn. Brooklyn College. 12 Feb. 2009. Web. 5 Nov. 2013. "The Romantic Poets." Poet Seers. Sri Chinmoy Centre. N.d. Web. 5 Nov. 2013. Whitt, L. "A Poison Tree." University of Georgia. Franklin College of Arts and Sciences. N.d. Web. 10 Nov. 2013.