Unit 7 Notes – Cell Cycle and Genetics DNA DNA IS THE GENETIC

advertisement

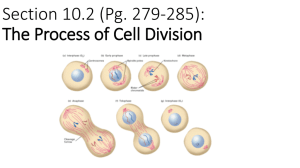

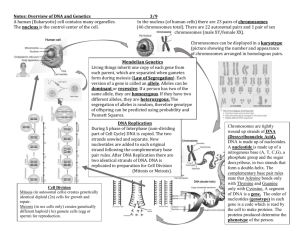

Unit 7 Notes – Cell Cycle and Genetics DNA I. DNA IS THE GENETIC MATERIAL There are several famous experiments that proved that DNA is responsible for inheritance. A. Bacterial Transformation Experiment (Griffith’s Experiment) Griffith used two strains of the Streptococcus pneumoniae bacterium that causes pneumonia in mammals. One strain was diseases-causing (pathogenic) while the other was a non-pathogenic strain. Griffith could change the harmless strain of the bacterium into a disease causing strain just by mixing dead harmful bacteria with live harmless bacteria. Transformation – 1. A change in genotype and phenotype due to the assimilation of external DNA by a cell. Question remains: What is the factor that is responsible for transformation? B. Avery, McCarty and MacLeod’s Experiments: They purified various molecules (proteins, carbohydrates, lipids and nucleic acids) from heatkilled bacteria and tried to use the purified molecules to transfer pathogenic characteristics into non-pathogenic bacteria. They used bioassays to determine the pathogenicity of various molecules. A bioassay is determining the activity of various molecules by testing their effects on living organisms and comparing the activity to various known molecules’ activity. Result: DNA is responsible for inheritance C. Bacteriophage Experiment (Hershey and Chase Experiment) Bacteriophages – viruses that kill bacteria (viruses are mostly composed of DNA or RNA and proteins) In this experiment, T2 phages were used that infect E. coli bacteria Results: Phage proteins remained outside of the bacterial cells while phage DNA entered the cells – radioactive DNA was detected inside of infected bacteria. Conclusion: DNA, not proteins are responsible for inheritance D. Chargaff’s Experiment: He analyzed the base composition of DNA from various organisms. Results: a. DNA composition varies from one species to another – evidence of molecular diversity among species b. In each species, the number of adenine bases approximately equaled the number of thymine bases; the number of cytosine bases equaled the number of guanine bases. (Chargaff’s rule) E. X-ray Crystallography (Franklin): Her X-ray crystallography photograph of DNA leads to the discovery of the structure of DNA. F. Watson and Crick Built the first model of the DNA molecule and described the structure of the molecule. They also predicted the process of DNA replication but did not have experimental evidence to support it. G. Messelson-Stahl Experiment Designed an experiment to determine DNA replication by tracing the origin of the replicated DNA. To tell the difference between the parental (template) DNA and the newly synthesized complementary DNA they developed a tagging system by using two different kinds of nitrogen isotopes. One isotope (14N) is the normal, light nitrogen, while the other (15N) is a heavy isotope. They could use centrifugation to separate heavy, medium weight and light DNA molecules from each other. II. Once they used heavy DNA as templates and allowed light DNA nucleotides to assemble with them, they got medium weight DNA molecules that showed that one half of the newly synthesized DNA was old (heavy) and the other half was new (light). DNA STRUCTURE Review this section from biochemistry or from Module 45 from your book. III. DNA REPLICATION: A. The Basic Ideas on DNA Replication Base-pairing rules apply when the DNA bases pair up The two strands are complementary, so each strand serves as a template for ordering nucleotides into a new complementary strand The process starts with one double helix and ends up with two DNA molecules, both double stranded and identical to the parent DNA Enzymes link the nucleotides together at their sugar-phosphate groups. The replication is semiconservative because every new DNA molecule contains one new strand and one old strand. http://www.sumanasinc.com/webcontent/animations/content/meselson.html B. A Closer Look at DNA Replication DNA replication is extremely accurate and efficient Although we know more about DNA replication in prokaryotes than in eukaryotes, we also know that the two processes are very similar. Six major steps of replication: a. Origins of replication: The site where DNA replication begins. In prokaryotic cells there is only one origin of replication, in eukaryotic cells there are hundreds or thousands to speed up replication. An enzyme (helicase) is used to untwist the DNA molecule. b. Initiation proteins recognize the origins of replication and open up the DNA double helix forming a replication bubble. Than replication proceeds in both directions until the entire DNA molecule is copied. Each opened DNA molecule where the replication takes place forms a replication fork. RNA nucleotides (primer) are used to mark the start of replication on each DNA polynucleotide chain. c. Elongating a new strand: Elongation is catalyzed by enzymes called DNA polymerases. d. Individual nucleotides align with complementary nucleotides along a template strand of DNA. DNA polymerase adds them one by one to the growing end of the new DNA molecule. DNA polymerize identifies the starting point by attaching to the prime of the RNA nucleotides In prokaryotes, there are two different DNA polymerases while in eukaryotes there are at least 11. The added nucleotides are actually nucleoside triphosphates (ATP, GTP, TTP, CTP but with deoxyribose sugar not ribose). When the Pi groups are broken down of the nucleotides, energy is released. This energy release fuels DNA replication. e. Antiparallel elongation: Because the two strands of the DNA molecule are antiparallel, so they are oriented in the opposite direction. The new DNA molecules also have to orient in the same direction. However, DNA polymerase can attach nucleotides only to the 3’ end and grows the chain toward the 5’end of the original chain. The original 3’5’ strand is called the leading strand because the DNA polymerase simply attaches new nucleotides by using the template of the old DNA chain and forms a new polynucleotide chain. To elongate the other new strand in the 5’- 3’ direction, the DNA polymerase works away from the replication fork, backwards. It forms small segments of the new polynucleotide chain that is going to be attached together later. These small segments are called Okazaki fragments. Another enzyme, (DNA ligase), attaches the Okazaki fragments together later. f. Only one primer is required to start the 3’ end but each Okazaki fragment requires a primer on the lagging strand. DNA polymerase I replaces the RNA primers with DNA molecular segments. An enzyme joins the sugar-phosphate backbones of the Okazaki fragments to form a continuous DNA polynucleotide chain. http://www.wiley.com/college/pratt/0471393878/student/animations/dna_replication/index.html -more detailed animation of DNA replication http://highered.mcgraw-hill.com/sites/0072437316/student_view0/chapter14/animations.html -- many things on DNA replication and the experiments http://207.207.4.198/pub/flash/24/menu.swf -- DNA replication, also very good http://www.fed.cuhk.edu.hk/~johnson/teaching/genetics/animations/dna_replication.htm -- basic DNA replication C. Proofreading and Repairing DNA In general there is only 1 error out of 10 billion nucleotides when the DNA molecule is being assembled. But the initial error rate is higher. DNA polymerases proofread the DNA molecule as it is being made and they replace the incorrectly placed nucleotide. Cells also have special repair enzymes to fix incorrectly paired nucleotides later. Most common factors that can result in the damage of DNA are: chemicals from metabolic reactions of the cell or from the environment, radioactive emissions, X-rays, UV light, spontaneous chemical changes of the DNA molecule. IV. Replicating the Ends of DNA Molecules: Because the end of the DNA molecule on the lagging end runs out of 3’ ends, it cannot be copied. As a result, each repeated round of replication produce shorter and shorter DNA molecules. The part of chromosomes that get lost at each DNA replication is called the telomere. Telomeres do not contain genes, they only have multiple repetitions of one short nucleotide segments (TTAGGG in humans). An enzyme called telomerase catalyzes the lengthening of telomeres in eukaryotic germ cells with the help of a short RNA segment. THE CELL CYCLE I. Overview Cells divide to replace old, dead or damaged cells, to grow the organism, the heal wounds, to reproduce the organism and maintain the species. Cells can divide by different methods: o Binary fission – the division type of bacteria and archaea o Mitosis – the type of cell division that produces identical copies of the same type of cell. This division is used in all cases when any somatic cell (body cell) forms. o Meiosis – produces haploid daughter cells that are genetically unique. These cells become the gametes (reproductive cells) of the organism. II. Binary Fission A simple process in which bacteria increase in size, replicate its simple circular DNA, grows some more and splits into two new identical cells. Scientists use fluorescent molecules to view this process under microscope. During harsh environments, bacteria switch to a division that produces endospores – resistant, dormant cell forms. Some of these forms can survive for thousands of years. Some bacteria produce spores normally as part of their life cycle. Others can perform budding, growing a new cell on the tip of the parent cell. III. Eukaryotic Cell Division This is your spring break assignment IV. Cell Cycle Control Different types of cells divide at different schedules. Skin cells divide continuously, liver cells divide only if some other cells died around them, muscle cells don’t divide, they can only repair themselves. Cell cycle control mechanisms determine if the cell will remain in the G1 or G0 phase of the cell cycle or continue to other phases. There are several different control mechanisms. Major cell cycle controls include: o Checkpoints – Protein signaling pathways are used to interact with molecules that are part of the cell cycle. These protein signaling pathways allow the cell cycle to continue only if the molecules that they interact with are complete and healthy. There is a checkpoint in the G1 phase, that check the size of the cell and the condition of the DNA. If this checkpoint is not passed, the cell remains in G0 phase and will not divide. There is another checkpoint in G2 to check if the DNA replicated properly in S phase and if the cell is large enough to divide. There is a last checkpoint during mitosis in metaphase to check if all the chromosomes attached to the spindle fibers. o Cyclin and kinase complexes – The cell cycle is also regulated by proteins called cyclins that increase in concentration at the end of each phase of the cell cycle. Cyclins bind with cyclindependent kinase (Cdks) molecules that are molecules with a constant concentration in the cell. The cyclin-cdk complexes are activated together to help the cell to switch to another phase of the cell cycle. After a new phase begins, the cyclins break down and the cdks become inactive again until the next increase in cyclin concentration. There are different types of cyclins produced in different phases of the cell cycle. These cyclin-cdk complexes trigger various cell signaling pathways. Cell cycle controls respond to various internal and external cues to determine when the cell needs to divide. External cues to regulate the cell cycle include: o Availability of nutrients o Growth factors – paracrine signals that are released by all kinds of cells to stimulate the division of certain area cells o Density-dependent inhibition – cells don’t divide if they touch other cells on all sides. There are surface proteins that bind cells to other cells. When all surface proteins are connected to other cells, the cell division will be inhibited until space opens up around the cell. Cancer cells don’t stop dividing and don’t recognize density-dependent inhibition. As a result, they form tumors. o Anchorage dependence – most animal cells don’t divide if they are not anchored to surface tissues. Cancer cells may not follow anchorage dependence, so they can divide during metastasis. Internal factors include the age of the cell. Normal cells divide only about 20-50 times before they die. Cancer cells can divide indefinitely so they are considered immortal. V. What Happens When the Regulatory Mechanisms Fail? Cancer is uncontrolled cell division of abnormal cells in the body. Cancer cells are different from normal cells because they don’t stop dividing when they fill up the available space or when they are not anchored to surfaces. They are also immortal in the sense that they don’t stop dividing. Cancer is caused by a set of mutations. These mutations make the cell recognizable for the immune system and in most cases cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells destroy cancer cells. But in some cases, the immune system fails to detect these cells. Than after further mutations the following stages of cancer occur: o Stage 1 – benign tumors – increased cell division forms small tumors o Stage 2 – benign tumors – small tumors increase in size and grow blood vessels to get nutrient and oxygen supply o Stage 3 – malignant tumors – tumor cells get into the blood stream and move to other parts of the body (metastasis) o Stage 4 – malignant tumors – secondary tumors grow all over the body. Cancer cells may look different under the microscope from normal cells and various changes occur in them. Genes that cause cancer are called oncogenes – the normal forms of these genes are called proto-oncogenes. These genes are normally responsible for controlling the cell cycle by for example producing cyclin proteins. Other genes called tumor-suppressor genes normally inhibit cell division. These genes stop cell division or stimulate apoptosis if the cell has mutations in their oncogenes. The most frequently altered tumor-suppressor gene is p53, which is mutated in more than half of all tumors in humans. Biointeractive – p53 activity Use your honors biology notes for the description of the cell cycle, mitosis and meiosis. THE SEXUAL LIFE CYCLE I. The Organization of Chromosomes Life Cycle – the sequence of stages an organism passes through from one generation to the next. The DNA of a cell is contained within structures called chromosomes which pass from one generation to the next. Diploid cells – have 2 copies of each type of chromosomes. If an organism has n types of chromosomes, diploid cells always have 2n by number. The two copies of chromosomes that carry the same type of genes but may carry different alleles of them are called homologous chromosomes. Somatic cells (cells that build up the body) are generally diploid in plants and animals. Haploid cells on the other hand have only one copy of each type of chromosome. Haploid cells are egg and sperm cells or gametes. Most animals and plants reproduce sexually by the fusion of two cells, the egg and sperm cells. Most single celled organism however reproduces asexually, with the splitting of one cell. These organisms have other ways to increase genetic variety. For example, bacteria can reach genetic diversity by transformation, conjugation and transduction. To form haploid cells, meiosis is performed. During this process diploid germ cells divide to form haploid gametes. Mitosis is the cell division of somatic cells. Karyotypes (a picture that has the chromosomes arranged in decreasing order by size and the sex chromosomes last) are used to determine gender or various chromosomal disorders. Cells contain two kinds of chromosomes, autosomes and sex chromosomes. Sex chromosomes determine the gender of an organism and secondary sex characteristics. In most organisms, XX stands for females, while XY stands for males. The number of chromosomes is a fixed number in each species but different species have different chromosome numbers. Later on we will use karyotypes and learn how to analyze them. II. Factors That Increase Genetic Variation Mutations -- sudden changes in the genetic makeup of an organism can result in new genetic combination. Random fertilization – during fertilization, any single sperm cell can fertilize any egg. As a result, the variety that is produced by the mating of the same two organisms can be tremendous. Crossing over – the process of the homologous chromosomes forming tetrads, overlapping with each other and exchanging some of their DNA during prophase I of meiosis, can result in a wide variety of genetic combinations. Independent assortment – During metaphase I of meiosis, homologous chromosomes (one from the dad one from the mom) line up in a random arrangement and separate from each other during the formation of gametes. GENETICS MENDEL’S PRINCIPLES I. Overview Gregor Mendel used pea plants to study inheritance. He came up with the basic principles of genetics in the mid-1800s. Pea plants were ideal experimental subjects because o They are inexpensive o Easily grown o Grows rapidly o Produces many seeds in a short time o Clearly observable traits o Easy to artificially fertilize The following key terms are necessary to understand Mendelian genetics: o P generation o F1 generation o o o o o o o o o o F2 generation True breeding Homozygous Hybrid Heterozygous Test cross Monohybrid cross Dihybrid cross Genotype Phenotype II. Mendel’s Principles: A. The Principle of Dominance Mendel said: Phenotypes depend on the particular inheritance of factors (alleles) coding for dominant and recessive traits. Only one copy of a factor (allele) coding for a dominant trait has to be inherited for that trait to be expressed in the phenotype. Today: The factors are alleles of the same gene Correction: Many traits do not follow dominant and recessive inheritance. These are called non-Mendelian traits. B. The Principle of Segregation Mendel said: Each organism has two factors (alleles) for each gene, one from each parent. Factors for the SAME trait are separated from each other during the formation gametes and get rearranged after fertilization. Today: Alleles for the same gene get separated during meiosis (haploid cells form) and get paired up again during fertilization. Correction: None C. The Principle of Independent Assortment Mendel said: Factors for DIFFERENT traits separate from each other during the formation of gametes and get rearranged again during fertilization. Today: Alleles for different traits separate from each other during meiosis and get rearranged again during fertilization. Correction: It is chromosomes not genes that separate, so if two genes are located on the same chromosomes, they do not assort independently, they are said to be linked genes and inherited together. III. Laws of Probability Probability examines how likely it is that an event will occur. Probability ranges from 0 to 1. Multiplication rule – Predicts the probability of independent events. Each individual probability is multiplied to obtain an overall probability. Addition rule – predicts the probability of mutually exclusive events. Mutually exclusive means that if one event occurs, the other event cannot occur simultaneously. So the probability of event A is added to the probability of event B. (If you flip a coin and you get a head, than you have no chance of getting a tail during the same toss.) IV. Monohybrid and Dihybrid Crosses We use Punnett squares to determine the potential outcome of each cross during a genetic problem. On one side of the Punnett square we list the father’s gametes, than on the other side it lists the mother’s gametes. The cells of the square represent the possible outcome of the cross for the next generation. Monohybrid crosses are used to determine the possible outcome of the next generation by following one trait at a time of two heterozygous parents. Dihybrid crosses are used to determine the possible outcome of the next generation by following two traits at a time of two heterozygous parents. See your Spring Break Assignment II for practice problems. VI. Chi-Square in Genetics We can test if a genetic cross follows the predicted type of inheritance and independent assortment by using Chi-square tests. If the observed data differ substantially from what would have been expected from our Punnett square and probability calculations, we can assume that the original prediction of inheritance type and independent assortment are not true. The null hypothesis (H0) in this case should be the predicted type of inheritance or the fact that the observed traits follow independent assortment. We will practice this on a handout and during a lab activity. VII. Non-Mendelian Patterns of Inheritance Genes that don’t follow simple dominant-recessive inheritance are categorized into following non-Mendelian inheritance. Incomplete dominance – In this type of inheritance the dominant allele is not strong enough to overpower the recessive allele. As a result, the heterozygous genotypes will have an intermediate phenotype of the dominant and recessive phenotype. (Like the colors of snapdragons, white and red, becomes pink when heterozygous) Codominance – alleles that are equally dominant combine to form a phenotype. (Like IA and IB combine to form AB blood group.) Polygenic inheritance – some traits are determined by multiple genes and the phenotypes can occur on a range instead of having two distinct types. The range of the phenotypes can be represented with a bell curve. (Ex. Human skin color, height, hair color etc.) The environment may also affect the phenotype – multifactorial characteristics – for example human skin color is affected by the exposure to the sun. The environmental factor can be related to diet, climate, illness and stress. (Other examples: plants grow shorter on higher elevations, humans grow shorter if nutrition is not sufficient, hydrangea plants have different flower colors depending on the pH of the soil – blue in acidic and pink in basic soil) VIII. Inheritance Patterns in Humans There are very few human traits (consistency of earwax, Huntington’s disease, albinism) that follow simple dominant and recessive inheritance. Most traits are more complex and may have multiple inheritance types depending on what level of organization we are examining. Sickle cell anemia: a blood disease that is characterized by crescent shaped red blood cells due to misfolded hemoglobin molecules. These red blood cells get stuck in small capillaries and cause pain and decreased blood supply. Sickle cell anemia is caused by a recessive gene (point mutation). Heterozygous form causes sickle cell trait, a milder form of the disorder. Review the evolutionary significance of sickle cell anemia. CHROMOSOMAL INHERITANCE I. The Chromosomal Theory of Inheritance Sutton proposed that the pairing and separating of chromosomes during meiosis and fertilization is the basis of Mendelian inheritance because the units of inheritance are chromosomes not genes – this is the chromosomal theory of inheritance Morgan did experiments with fruit flies to come up with greater detail on the chromosomal theory and experimentally prove Sutton’s findings. Morgan first used wild type fruit flies that had most of the commonly used fruit fly characteristics. He concluded the following: o Some traits are inherited differently in males and females due to their location on sex chromosomes – sex linked traits o Linked genes are inherited together and do not follow the principle of independent assortment II. Sex-linked Genes All chromosomes in organisms are similar in both genders except the sex chromosomes. The chromosomes that are not different in males and females are called autosomes. The main role of sex chromosomes is to determine gender specific characteristics. In most organisms, including fruit flies and humans, XY determines males, XX determines females. The Y chromosome does not carry the same genes as the X chromosome. The Y mostly has genes that determine maleness, but the X chromosome has some important genes that are not related to gender. These include genes for color vision (if recessive, colorblindness occurs) and for normal blood clotting (if recessive, hemophilia occurs). Genes that are located on the sex chromosomes are called sex-linked genes. These genes are either located on the X chromosome or on the Y. These two chromosomes do not carry the same genes. Although females have two X chromosomes, in functioning cells one of the X chromosomes is inactivated. The inactive X chromosome forms into an object called a Barr body. Most genes in the inactive Barr body are not expressed, so females don’t have excess numbers of proteins of the genes that are on the X chromosomes. The Barr body formation is random, so every cell randomly has one or the other X inactivated. You need to be able to solve genetic problems with X-linked, Y-linked inheritance and apply these on pedigrees. III. Gene Location Determines Linkage When genes are linked, the only way to get new combinations of them is by crossing over. Otherwise the genes that are located on the same chromosome are inherited together. As a result, during dihybrid crosses, most of the offspring will follow the parental phenotypes but crossing over will result in new combinations of phenotypes that are different from the parents. These new combinations of phenotypes are called recombinants. The closer two genes are to each other on a chromosome, the less frequently they recombine. The frequency of recombination between two genes can be used to map up chromosomes and compare the location of different genes to each other on the chromosome. These maps of genes on chromosomes are called linkage maps. To calculate the recombination frequency and the map units between two linked genes we use: See given handout on how to calculate recombination frequencies and form linkage maps. MUTATIONS I. Types of Mutations Mutations are sudden, heritable changes in the genetic makeup of an organism. These mutations can occur in the somatic cells or in the gametes. The somatic mutations are only passed on to the cells that form from the mutated somatic cell by mitosis. Mutations of the gametes are passed on to the next generation of organisms. These mutations can be gene mutations if they only affect one single gene, or chromosomal mutations if they affect entire chromosomes or sets of chromosomes. II. Gene Mutations Point mutations – occur if only one single nucleotide is substituted in the gene from one type of base to another (Ex. An A changes to a G) Deletions – The loss of one or more nucleotides in a DNA sequence Insertions – The addition of one or more extra nucleotides in a DNA sequence Insertion or deletion of nucleotides can result in frameshift mutation if the number of nucleotides being deleted or inserted is not multiples of three. Frameshift mutation has serious consequences, because the gene will determine an entirely different sequence of amino acids or determines a stop signal that will stop the translation process before a complete protein can form. According to the results (outcome) of point mutations, we can have one of the following: o Silent mutation – the mutation does not result in a change of the amino acid sequence, so the mutation does not show up at all o Missense mutation – the mutation causes one amino acid to be mistaken and can result in a misformed protein o Nonsense mutation – results in an early stop codon that stops the formation of the polypeptide chain without completing it. III. Chromosomal Mutations: A sudden change in the number or structure of the chromosomes results in chromosomal mutations. These changes generally result in major changes in the genetic makeup of the organism. Serious birth defects or other major issues can result. The changes can occur in the structure of the chromosomes: o Inversion – part of the chromosome breaks off and reattaches in the opposite direction o Translocation – part of the chromosome breaks off exchanges DNA with a nonhomologous chromosome o Deletion – part of the chromosome breaks off and gets lost o Duplication – part of the chromosome gets repeated. Changes can also occur in the number of chromosomes: o Aneuploidy – chromosomes don’t separate properly from each other during mitosis or meiosis (nondisjunction) so incorrect numbers of chromosomes result. The numbers of chromosomes in these cases are off by 1 or 2. o Polyploidy – entire sets of chromosomes are doubled or tripled due to nuclei not separating after the DNA already replicated. This case results in triploid, tetraploid etc. cells. Plants may have this condition but it is basically none existent in animals. Examples of aneuploidy include: o Down syndrome – trisomy # 21 o Klinefelter syndrome – XXY sex chromosome (male gender) o Turner syndrome – XO IV. Causes of Mutations: DNA polymerase errors can cause mutations if these errors are not fixed during proofreading Mutagens – environmental factors can also cause mutations by permanently changing the DNA structure. Ionizing agents such as X-rays, gamma rays can cause mutations by creating free radicals that will still electrons from other molecules in DNA. UV radiation can form Thyminethymine dimers within the same polynucleotide chain. Various mutagenic chemicals can add or break segments of molecules off of DNA (like nitrogen mustard) V. Karyotypes Pictures that represent the chromosomes arranged in order by decreasing size and the sex chromosomes separated at the end. Karyotypes can be used to determine the gender of a fetus, to determine chromosomal mutations during pregnancy by taking amniotic fluid from the mother and look for fetal cells in it. Karyotypes are effectively constructed when cells are in prophase of metaphase of mitosis. You must be able to analyze karyotypes of normal persons and karyotypes with various chromosomal disorders.