Contrib_Model_2_2015-Girls

advertisement

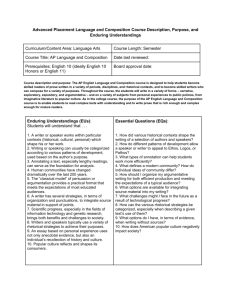

CONVERSATION CONTRIB MODEL 2 1 Name Instructor FYE Orientation 20 January 2015 2,408 words Writing as Personal and Social Act: Finding a Voice of a Generation Anyone familiar with creative writing knows the clichéd injunctions to “write what you know” and “find your voice.” These instructions suggest that the writer’s experience and identity should serve as her spirit guides on the path to success. Writing about the development of the university creative writing program, Mark McGurl argues that these seemingly self-centered koans are better understood as reactions against the institutionalization of creative writing: dictums meant to romanticize and prioritize the self and its unique experience as the fount of creativity. McGurl’s 2009 study of university creative writing programs, The Program Era, enters into an ongoing conversation about the proper motivation for a writer: the self or society, the writer or her audience. McGurl suggests that the writer is part of a larger culture of writing that implicates the MFA student and autodidact alike, as well as their readers, pointing to the more complicated dynamics that motivate and shape acts of writing. Like McGurl, I intervene in this conversation to shed light on romantic myths about the one-way relationship between the writer and her creation. Taking the character Hannah Horvath from the show, Girls, as my object, I will argue that the belief that writing reflects a writer’s individuality keeps us from recognizing how public and private uses for writing always shape what the writer puts on the page. Writers Are Just A Bunch of Narcissists CONVERSATION CONTRIB MODEL 2 2 It sounds like a truism to call today’s youth narcissistic; the “me generation” has been called out for using new media platforms to stroke their egos, crafting ideal selves through Facebook pages, Twitter feeds, and Instagram selfies. While digital media may seem to encourage today’s narcissists, the printed page remains a romanticized space for selfconstruction and self-promotion, and the status of “writer” maintains considerable caché. As early as 1905, Virginia Woolf bemoaned “the invention of the personal essay” for encouraging writing that “is not interesting, cannot be useful, and is a specimen of the amazing and unclothed egoism for which first the art of penmanship and then the invention of essay-writing are responsible” (1; 2-3). Her feeling that the culture encourages writers to subject readers to their purportedly useless prose is echoed in more recent musings by Laura Miller, who reads the motivational event, National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo), as a permission for novice writers “to write a lot of crap” that they “insist…other people read” (3). Cristina Nehring takes a similar stance in her essay about the status of American essays, citing the lack of “courage” among writers to “address large subjects in a large way,” and focusing instead on the “Slowmoving. Soft-hitting. Nostalgic. [and] Self-satisfied”; in other words, on personal matters of little interest to potential readers (2;3). Woolf, Miller, and Nehring paint writers (or at least “bad” writers) as selfish and readers as “selfless” (Miller 3). In the context of Miller’s essay, “the selfless art of reading…[has been] taken over by the narcissistic commerce of writing,” which can wring more money from wannabe writers who flock to how-to books and motivational writing seminars. Members of the narcissism camp critique the self-interest ostensibly motivating writing and the market that encourages such essays and fiction. To this end, Miller points out the “homogenous” tone of today’s essays based on her reading of works anthologized in The Best American Essays CONVERSATION CONTRIB MODEL 2 3 collections. These anthologies produce a “composite portrait of the Preferred American Essayist: Educated at Harvard, he or she has spent significant time at the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference, written proposals for New York Public Library Fellowships…and received medical attention at Sloan Kettering Hospital” (3). Nehring’s essay suggests that there are networks of privilege supporting the image of the writer that emerges from these anthologies, but she does not consider where the target audience of such prose fits in relation to these networks. The stereotypical writers in the Best American Essays anthologies are, ironically, the successful writers that “wannabe” NaNoWriMo participates aspire to become. But what might we glean about the narcissistic tendencies of writers if we looked beyond the myth of the writer motivated only by her own self-regard, shrouded in privilege? Those who focus on the writer’s self-motivation reproduce what James E. Porter describes as “the romantic image of writer as free, uninhibited spirit, as independent, creative genius” (34). Writing is not merely self-expression in this view; writing “what you know,” as per the creative writing mandate, means writing what your discourse community knows, and also recognizing when the texts you read are not quite accessible to you. Writing about the role literature can play in the composition classroom, Mark Richardson remarks on the student’s “reluctan[ce] to step onto hallowed ground” and engage in ongoing debates about the meaning of literary texts. Students see literature as mythic and removed from their social world, much like the romantic image of the genius writer; there remains a “hierarchical relationship between student and text embedded in our cultural assumptions about truth, beauty, and art” (281). Writing, then, is more than self-expression, even if the subject matter is the self; it is an exercise in self-construction based on one’s social position and the kind of audience one hopes to address. The market economy, and not merely the symbolic economy of truth, beauty, and art, CONVERSATION CONTRIB MODEL 2 4 also influences the conditions under which a writer or artist produces her work. Describing the different kinds of television shows aired on network and cable TV, Derek Thompson explains that “The economic structure of cable channels, which receive most of their money from fees rather than ads, greatly relieves them of the burden of maximizing audience–and as a result they produce television that is less formulaic, more attractive to the writing- and-reading-about-TV crowd, but often less watched” (3). This economic logic is part and parcel of the “hierarchy” Richardson describes; both difficult literature and less formulaic, premium TV shows appeal to small, more elite niche audiences who have both the real and symbolic capital necessary to enjoy them. I want now to turn to the character Hannah Horvath from Girls whose education, family background, and race make her the elite, tacit addressee of capital-L “Literature,” even as her beginner’s status makes her an outsider to the writing establishment. Seeing how the show complicates the myth of the “free, uninhibited” writer (Porter 34)—even if Hannah does have certain privileges—sheds light on the institutional and economic factors that situate the writer and motivate the kind of work she produces, whether consciously or not. A Voice of a Generation Girls follows the misadventures of aspiring 24-year-old writer Hannah Horvath who must balance her desire to be an artist with her need to support herself in Brooklyn. The first episode juxtaposes the fantasy of being a writer in New York City with the bleaker reality of struggling to gain a foothold in the industry. The first scene shows Hannah in an upscale restaurant with her parents, greedily inhaling food as she reminds them that she’s a “growing girl.” Though Hannah’s remark infantilizes her, her parents want her to embrace her adult independence, telling Hannah that, after two years of financial help, they will no longer “keep bankrolling [her] CONVERSATION CONTRIB MODEL 2 5 groovy lifestyle.” It is not inconsequential that this “groovy lifestyle” is the foundation for much of Hannah’s writing. She is currently working on a memoir, a collection of essays that is currently incomplete because, as she claims in order to maintain financial support from her parents, she has to “live them first.” Immediately the show establishes the contrast between Hannah’s own romanticized idea of the writer—in particular, the personal essayist—and the economic reality in which she finds herself. In this image, the writer’s life is the foundation for her art, and her art in turn creates her as a particular kind of person. As Hannah explains, she has been “busy trying to become who I am”; she understands this “busy”ness of living as coterminous with the business of writing. But as the show goes on to explore, the notion that a writer can sit back and write about her life as a writer, focusing intently on herself without thought of an audience or public, is a myth even for Hannah, who TV critics repeatedly label a “narcissist” (Kay). The first episode pokes holes in the fantasy of the privileged writer whose craft can support her lifestyle. Later in the episode, the character Shoshanna remarks on a Sex in the City poster, debating which of the characters she’s most like. The main character of Sex in the City, Carrie, was, like Hannah, a personal essayist, but Sex in the City rarely showcased her financial struggles and Carrie was already a professional writer. The first episode ultimately undercuts the myth of the successful writer as at liberty to write only for and about herself. In season two, episode three, Hannah’s first paid writing job—a freelance position for the fictional blog jazzhate—reveals how the writing she produces, despite its focus on herself, is nevertheless influenced by the blog’s audience’s expectations of scintillation and scandal. The blog editor explains to Hannah that they’re looking for writing about events that occur outside the writer’s comfort zone. Hannah asks if “there [is] something you want me to explore CONVERSATION CONTRIB MODEL 2 6 specifically?” “You could do a whole bunch of coke and then just write about it,” the editor responds, which starts Hannah on an anxious rant about how drugs and her delicate constitution don’t mix. Nevertheless, the episode revolves around Hannah taking cocaine for the first time in order to drum up a story worthy of the $200 the blog will pay her. Hannah’s writing, and the personal experience on which it’s based, is ultimately shaped by the demand of her public. The episode traces the feedback loop between Hannah’s personal writing and the public for whom she composes it. More than being influenced by her audience’s expectations, Hannah is motivated by the money she needs to earn from the piece, suggesting the multiple influences that shape her composition. Despite my argument that Girls’s Hannah reveals the more complex motivations of writers, it could be argued that Hannah remains the classic narcissistic writer that Woolf, Nehring, and Miller describe. Even in her work for jazzhate, she writes about herself and her experience, fancying herself the kind of person whose exploits are worthy of publication. But Girls expands its view of writers and their art, moving beyond the writer-essay focus of those in the “narcissist camp.” Girls is more conscious of the audiences that certain genres of writing court and provides snapshots of the ways in which writing and writers circulate. Even Hannah is able to see beyond her ego to recognize that she and her writing are not representative of all writers or readers and may be of interest to (and representative of) only a particular public. As she tells her parents in the pilot episode, in a last ditch effort for their continued financial support, “I think that I may be the voice of my generation. Or at least a voice of a generation” (emphasis mine). In the second episode of the first season, the show comments again on this difference between the fantasy of a homogenous public and the diverse kinds of readers texts may CONVERSATION CONTRIB MODEL 2 7 encounter: the difference between “the” public “a” public. This time, the characters debate whether or not they are “the ladies” being addressed in a popular dating advice book. After discussing certain dating rules described in the book, Hannah asks her friends, “Who are the ladies?” To which Shoshonna replies “Obvi[ously], we’re the ladies,” with Jessa retorting, “I’m not the ladies.” By showing us how the public of a piece of writing responds to work that does not seem addressed to them, Girls helps us understand a weakness in the narcissist camp’s view that acts of writing motivated by self-interest or personal-gratification are necessarily useless to readers. Readers make meaning of texts even if that meaning, as in Richardson’s classroom, may initially be a meaning about their relationship to a text and not the text itself. Girls helps us see the connection between Hannah’s personal writing and the dating advice book the characters discuss; both are informed by particular discourse communities, and not everyone may consider themselves addressed by those texts. Hannah’s prose may not speak to the college writing students who are the subject of Richardson’s article, but even in her selfabsorption, Hannah recognizes this. She is possibly a voice of a generation, a mouthpiece for a particular subset of her peers, but by no means is she wholly representative. This admission and this self-awareness are what writers in the narcissism camp sidestep, remarking on the stereotypical writer anthologized in The Best American Essays collections, but glossing over the kind of public this anthology addresses. While the “big ideas” that used to be in essays are presumably universal, Nehring overlooks the ways in which the seemingly narcissistic “miniature” can be mined for insights about “truth” and the specific writer-public community who consume texts. Though those in the narcissist camp want writers to strive for universal truths that can be of use to readers, they disregard how the notion of “universal” is itself a construct. Detractors of narcissistic writers glorify reading and universal truths at the expense of CONVERSATION CONTRIB MODEL 2 8 recognizing how their own motivations to do so are shaped by the more specific discourse communities to which they and narcissistic writers belong. In many ways, the romantic myth of the individual writer keeps us from seeing the more complicated dynamics shaping a writer’s production. Conclusions Despite the drawbacks of the narcissism camp, their moralizing tone serves to reinvest the act of writing with social value, suggesting that writing has a loftier goal than self-promotion and self-satisfaction. However, even in its tacit suggestion that “good” writing has the philosophical goal of tackling “big ideas” beyond the self, this argument overlooks how “big” and varied an audience and their response to writing can be. Studies that pretend to know what motivates a writer neglect how that writer’s very sense of self is shaped by myths about writing. Girls shows us how finding your voice and writing what you know involves acts of selfconstruction and textual composition that are shaped by larger symbolic and economic networks. CONVERSATION CONTRIB MODEL 2 9 Works Cited Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi. “The Dangers of a Single Story”. TedGlobal. Jul 2009. ted.com. Web. 2 Jan. 2014. Girls. Seasons 1&2. Writ. Lena Dunham. 2012. Kay, Lena. “Why I Don’t Like ‘Girls’.” The Huffington Post. 06 March 2014. Web 19 Jan 2015. McGurl, Mark. The Program Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009. Kindle file. Miller, Laura. “Better Yet: Don’t Write that Novel”. Salon.com. 02 Nov. 2010. Web. 29 Dec. 2014. Nehring, Cristina. “What’s Wrong with the American Essay”. Truthdig.com. 29 Nov. 2007. Web. 29 Web. 2014. Porter, James. “Intertextuality and the Discourse Community”. Rhetoric Review. 5.1 (Autumn 1986): 34-47). jstor.org. Web. 29 Dec. 2014. Richardson, Mark. “Who Killed Annabel Lee: Writing about Literature in the Composition Classroom”. College English. 66.3 (Jan. 2004): 278-93. jstor.org. Web. 27 Feb. 2012. Thompson, Derek. “Why Nobody Writes about Popular TV Shows”. The Atlantic. May 2004. theatlantic.com. Web. 29 Dec. 2014. Woolf, Virginia. “The Decay of Essay-Writing”. [Source under review]