Scholarly definitions thus link the linguistic act of translation with

advertisement

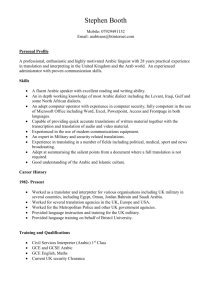

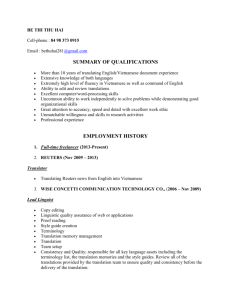

Matthew Mermel LING 487 Industry Research Report 1 Building an Arabic Transcreation Practice Introduction Globalization, the integration of international socioeconomic communities fueled by rapid advances in information and transportation technology, exists as an indisputable fact of life in the Internet era. Yet, despite the spread of English as the international business world’s lingua franca, the translation industry continues to grow and expand with profit projections regularly surpassing more than $20 billion each year (Sprung 2000). Accordingly, multinational firms from Apple to Nike and everywhere in between increasingly invest millions of dollars in translation and location services, defined as the adaptation of products, services, and messages from one culture to the sociolinguistic standards of another. The language service industry, the sector which facilitates international and multilingual business communications, proves indispensible to the process of translation and localization; duties performed by language service industry include translation, interpretation, language technology development, and linguistic consulting (ECLI). Of the industry’s array of manifestations, transcreation, the “adaptation of a message from one language to another, while maintaining its intent, style, tone and context,” (Morrison 2013) displays the greatest future growth potential and, moreover, aligns most closely with my own professional and academic skills and interests. As such, the following industry research report introduces and analyzes the practice of transcreation, performs a case study of Craft Worldwide, explores possibilities for developing an Arabic language transcreation practice, and delineates how I plan to launch my career in the field. Matthew Mermel LING 487 Industry Research Report 2 Transcreation Accurate, effective translation goes far beyond simply substituting the words of one language with their equivalent terms in another. Rather, it requires the adaptation and transmission of the original message’s intent, context, style, and tone and to the target language as well. Bell supports this assertion, describing translation as “the expression in another language...of what has been expressed in [the] source language, preserving semantic and stylistic equivalencies,” (1991:5). Scholarly definitions thus link the linguistic act of translation with awareness and understanding of the target language’s culture, its communicative norms, and expectations—all of which fall precisely within the domain of sociolinguists. Industry professional Matt Moore essentially states as much, writing that a linguistic “approach to translation focuses primarily on the issues of meaning and equivalence (same meaning conveyed by a different expression)...[that] tries to discover ‘what’ the language actually means,” (Moore 2009) rather than merely what is said. All the while, “it is necessary to be clear about the cultural differences between the foreign language and the native language and how the target-language culture is reflected in its language” (Geng 2013:977). In essence, then, “Translation is not a matter of words only: it is a matter of making intelligible a whole culture ,” the agentive act of “[trans]creating a text for the target audience,” (Balemans 2010). Robert Sprung (2000), “founder and manager of the translation and transcreation unit within CRAFT Worldwide [this Indurstry Research Report’s company of inquiry] ” (LinkadsfedIn) regards translation as the cross-cultural transmission and adaption of messages from one sociolinguistic standard to another. According to Bassnet Matthew Mermel LING 487 Industry Research Report 3 (1998: 79-81) task of the translator, therefore, “is not to ignore cultural differences [or] to pretend that there is such a thing as universal truth and value free [of] cultural exchange, but rather to be aware of those differences,”—a matter I am keenly aware of and familiar with. My Interest in the Field: Why Transcreation As a sociolinguist, I am broadly interested in the professional applications of sociolinguistic analysis and using my linguistic training to overcome challenges of intercultural communication. Gumperz (1982), and Scollon (1996) establish the critical nature contextual knowledge to sound cross-cultural communications; from applied experience working abroad in the Kingdom of Jordan, during which time I bidirectionally translated official project documents for government institutions Arabic-English, I understand how crucial sociolinguistic knowledge of and experience in the target culture proves to effective and accurate translation (Homeidi 2004). Accordingly, I hope to combine my formal linguistics training and Arabic language skills in a productive capacity for international language service provider firms operating in Arabic speaking countries. Transcreation, which requires one with “ an excellent knowledge of both the source language, the target language [and] a thorough knowledge of [the target language’s]cultural backgrounds,” (Balemans) provides the ideal career path in which to apply my personal, professional, and academic interests. Craft Worldwide, Industry Leader Seeking to apply sound linguistic principles to “leverage brands and products Matthew Mermel LING 487 Industry Research Report 4 worldwide,” (Sprung 2000:ix) while solving the types of linguistic problems frequently encountered in the international business world, language and linguistic analysis forms the very core of Craft Worldwide’s key competencies. As a pioneer in the field of transcreation, “seamless [socioculturally relevant] adaptation is at the heart of Craft Worldwide’s value proposition,” (craft-translation). To that end, Craft employs keen-minded, analytical interculturalists with a “love of language and drive to solve linguistic problems...to transmit [a] brand’s message, intact, from one market or cultural group to another,” (craft-translation). Working with Fortune 500 clients as diverse as Coca-Cola, General Mills, and Xbox, Craft conceives of its employees as agentive ‘craftsmen’, who, equipped with their array of foreign language skills, linguistics training, and functional-area (i.e., industry) expertise and experience meld and mold language in a variety of different manners and methods as per client requests and target culture needs and expectations. Craft’s referring strategy on its website thus positions language as a powerful, malleable tool used to communicate messages across cultures and different languages. Accordingly, the company both considers and employs language in ways that intercultural scholars such as Gumperz and Scollon, with their emphasis on cultural and contextual knowledge, would endorse: Craft, in short, seeks skilled and motivated employees with the repertoire of foreign language, linguistic, and analytical skills to overcome the inherent challenges of cross-cultural communications and marketing. Matthew Mermel LING 487 Industry Research Report 5 My Fit at Craft Greg Niedt, former employee in Craft Worldwide’s Translation and Transcreation department, current translation project manager at Shuttershock, and MLC alum (Class of 2011) provided my initial introduction to the company by way of an informational interview. Regarding the relevant skills and experience that transcreation firms seek in job applicants, Greg stated that companies most value those candidates possessing previous translation and transcreation experience and a demonstrated academic and professional passion for language. Given my hands-on Arabic-English translation and transcreation experience as a project manager in the Kingdom of Jordan, I fit the bill in both respects: During the summer of 2012, I translated a Ministry of Planning and International Planning internship project manual Arabic-English and a demography survey proposal English-Arabic for the Ministry of Social Development; subsequently, as the principal project consultant for a start-up hearing aids manufacturer, I authored and secured a $50,000 CAD grant from the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives; created a Site Master File in English as per ISO-9000 standards for and approved by the Jordanian Food and Drug Administration to gain GMP and ML (Manufacturing and Marketing) licenses; and completed the start-up registration process with the Jordanian Customs Department to being operations as an official medical device vendor in the country. These past experiences, as well as my current job transliterating and translating Arabic books, journals, and DVDs as Georgetown University’s Arabic Metadata Specialist constitute the exact type of “unique trial-byfire background they'll [translation firms] want to see.” Matthew Mermel LING 487 Industry Research Report 6 Greg further made the crucial distinction between the roles of translator and project manager at transcreation firms. Companies expect translators to translate into their native language (i.e., a native Arabic speaker bilingual in English translates from English into Arabic, while a native English speaker bilingual in Arabic translates from English into Arabic), possess relevant certificates and education in their given translation language(s), and meet industry standards for quality control words translated per minute. Project managers, on the other hand, largely “traffic documents, deal with clients, and proof-reading/spot-checking across many languages.” As a native English speaker proficient in Arabic with graduate-level linguistics training and experience transcreating official project documents Arabic to English, I thus appear best suited for a project management position with a transcreation and translation firm. Following my informational interview with Greg, I contacted Robert Sprung, founding manager of Craft Worldwide’s Transcreation unit, to inquire about an informational interview. While we have yet to speak by phone, Robert indicated over email that he is interested in building an Arabic practice at Craft, a proposal towards which my report now turns. Proposal for an Arabic Practice As established, effective and accurate translation from one sociolinguistic standard to another requires individuals intimately familiar with the target culture, its language, and expectations for socially acceptable behavior. Given my academic and professional background with the language, I constitute the ideal project manager for an Arabic transcreation unit. I understand the sociocultural nuance, Matthew Mermel LING 487 Industry Research Report 7 depth, and expectations of Arab communities; possess the Arabic language skills, linguistics training, and applied transcreation experience coveted by translation and localization firms; and, moreover, have experience performing a variety of duties in a managerial capacity. As the Arabic project manager, then, I will be responsible for networking, liaising, and negotiating with client corporations whose advertisements we will transcreate for the Arabic marketplace; trafficking documents; proofreading translated texts; and managing workflow. In order to best preserve clients’ “signature style in the foreign-language copy” (Sprung 2000:13), I further propose hiring two native Arabic-speaking translators on a freelance basis, adding more as our unit expands. In addition to myself, the initial Arabic will include: one literary translator who excels with technical materials and “is used to delivering high volumes on tight deadlines,” (Sprung 19); and one technical translator, “who can recreate the [source] voice in a foreign language,” (Sprung 19). Expected to possess sound research and analytical skills, these translators should demonstrate “strong fluency in English, with a keen ear for idiom,” and, “a professional, fluid style in the target language, with a penchant for brevity,” (Sprung 20). Working from English into their native language, they must possess certificates from accredited institutions verifying their skills as English-Arabic translators, a solid record of past translation experience and success, and demonstrate familiarity with computerized translation tools such as Trados and MemoQ. Ideally, they will also have past experience working on international marketing campaigns. 8 Matthew Mermel LING 487 Industry Research Report Arabic Practice Transcreation Workflow As the Arabic project manager, I will network, negotiate, and secure contracts with client corporations whose marketing campaigns and communications our team will transcreate for the emerging Arabic language marketplace; transfer and track documents, proofread translated texts, and manage workflow as per a documented quality control procedures, a model of which appears below (adapted from Sprung 22-23): Text/Ad Campaign Received Presented to Client Tracked by Management Software Edited and Proofread Translated by Native Speaker EnglishArabic Focus Group Review by All Team Members Regular review sessions of current projects will prove particularly crucial to the Matthew Mermel LING 487 Industry Research Report 9 Arabic unit’s success: during these meetings, I will lead the translation team in a principled evaluation premised in linguistic analysis to determine how to best adapt and transmit message tone, intent, context, and affect from English to Arabic. Going Forward Going forward, I will continue to engage the industry by monitoring social media and professional blogs, reading about the trade in non-scholarly and academic sources, and researching companies like Craft and Hogarth, another renowned transcreation firm. Networking has and will continue to prove most effective as I seek a career in the field. Via Shelley Morrison, whose transcreation workshop I attended at the SIETAR conference in November 2013 and reconnected with at the 2014 International Management Conference, I connected with Meritxell Guitart, president of Hogarth Americas, and interviewed in-person for a summer internship position with their transcreation team in New York City. Additionally, I interviewed by phone with both Craft Worldwide and RR Donnelly Global Language Services for a similar positions on their translation and transcreation teams. As of this writing, I am awaiting final word from all three corporations regarding my summer employment and will update this report accordingly upon notification of their final decisions on my candidacy. Matthew Mermel LING 487 Industry Research Report 10 REFERENCES Balemans, Percy. (7/14/2010). Transcreation: Translating and Recreating. Translating is an Art. Retrieved 3/6/14 from http://pbtranslations.wordpress.com/2010/07/14/transcreationtranslating-and-recreating/. Bassnett, S. (1998). Translation Across Culture, in Language at Work. British Studies in Applied Linguistics 13, 72-85. Bell, Roger T. (1991). Translation and Translating: Theory and Practice. New York: Longman Inc. Translation. CRAFT Worldwide. Retrieved 3/6/14. http://www.craftww.com/translation/ Homeidi, M. A. (2004). Arabic Translation Across Cultures. Babel 50(1), 13-27. Geng, Xiao (2013). Techniques of the Translation of Culture. Theory and Practice in Language Studies 3(6), 977-981. Gumperz, John J. (1982). Interethnic Communication. Discourse Strategies, 172-186. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Language Industry Web Platform. European Commission. Retrieved 3/6/14, from http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/translation/programmes/languageindustry/platf orm/index_en.htm Moore, Matt. (11/19/2009). The Linguistic Approach to Translation. One Hour Translation Blog. Retrieved 3/6/14 from http://blog.onehourtranslation.com/linguistic-service/the-linguisticapproach-to-translation/ Matthew Mermel LING 487 Industry Research Report 11 Scollon, Ron (1996). Discourse Identity, Social Identity, and Confusion in Intercultural Communication. Intercultural Communication Studies 6(1), 1-16. Sprung, Robert and Simone Jaroniec (2000). Translating into Success. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company Sprung, Robert (2014). Robert Sprung. LinkedIn. Retrieved 3/6/14 from http://www.linkedin.com/profile/view?id=48467655&authType=NAME_SE ARCH&authToken=XdIT&locale=en_US&srchid=2796647731394166555604 &srchindex=1&srchtotal=13&trk=vsrp_people_res_name&trkInfo=VSRPsear chId%3A2796647731394166555604,VSRPtargetId%3A48467655,VSR