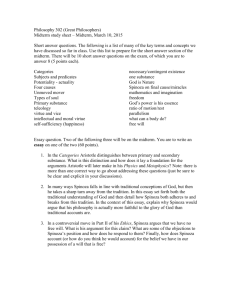

SPINOZA AND DESCARTES - MIND, BODIES, AND ACTION

advertisement

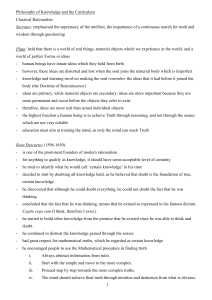

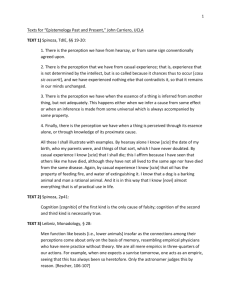

SPINOZA AND DESCARTES - MIND, BODIES, AND ACTION For Spinoza mind and body are the same substance. Thus, mind and body are ontologically the same thing, the same reality or substance. The mind is inseparable from the body, and vice versa. He says, " the mind is united to the body because the body is the object of the mind" (Ethics 2, prop 21). But this does not mean that one determines the other or causes effects in the other, because in reality the mind and body are the same. They are different attributes of one fundamental reality. They are not causally related but intrinsically related, so we cannot say that one determines the other. Spinoza says that "the body cannot determine the mind to think, nor the mind the body to remain in motion or at rest" (Ethics 3, 2). This is because each acts simultaneously with the other, so it is illogical to say one determines the other. This unity of mind and body as one substance is in contrast to Descartes' belief that mind and body are separate substances. For Descartes the mind and the body are independent realities, each able to exist without the other. He proudly proves this beginning in the second meditation when he concludes that doubt is possible as to the true existence of the body but there can be no doubt as to the existence of the thinking mind since this is what is either believing or doubting. The mind cannot doubt the existence of thinking, since even the doubt itself would require thinking to exist! But since the body can be doubted, and it is possible for thinking to go on without knowledge of the body, then one can conclude an independent existence for mind. Thus, a duality of mind and body. He also tries to prove such independent substances in the sixth meditation, where he states, "there is a great difference between mind and body", because the body is divisible while the mind is not. I can, in my mind, divide extended things into parts, but "when I consider the mind, that is, myself insofar as I am only a thing that thinks, I cannot distinguish any parts in me; rather I take myself to be one distinct thing" (Meditation 6, 86). Spinoza does make a distinction, though, between thought and extension as two different attributes of the one ontological substance. Each thing is both thought and extension. The thought is what is known through ideas and the extension is what exists and is sensed physically. Thought is a mental property and extension is a physical property. While Descartes viewed thought as the property of mind and extension the property of bodies, Spinoza altered this view by asserting that a mind/body reality could be distinguished into separate attributes of thought and extension. Yet, this altering of Descartes' metaphysics may actually be a subtle trick of language, since instead of separating mind from bodies Spinoza separates thought from extension -- but what is the real difference? What really is the difference between dividing reality into two different substances or dividing substance into two different attributes? Either way there seems to be a fundamental division. Would not the problematic relationship between thought and extension be equal to that of mind and bodies? The difference between the two philosophical views may be that Spinoza views thought and extension as inseparable two sides of the same coin. For Spinoza mind and body, thought and extension, are parallel realities, not having independent existences or independent causal series; while with Descartes' division there are two distinct existences with two distinct causal series. Spinoza believed the mind and body are different conceptually but not ontologically. They are two different ways of description, just as we could describe music psychologically (or aesthetically) and physically (or in terms of physics). Thus, reality can be described in terms of causally ordered physical bodies or as logically ordered sequences of ideas. Yet, there cannot be two different causal sequences, one of the mind and one of the body, but the same sequence conceptually viewed in different ways. The mind and body, for Spinoza, act simultaneously, or as mirror images of each other, so we cannot even say that one determines the other. Thought is the consciousness of extension and extension is the manifestation of thought, and neither has any freedom from the other. But then, does the mind act according to mechanical determinism, as Descartes would view bodies? Or do bodies act as imaginably as the mind? If these are inseparable and simultaneous acts, then wouldn't my body change according to my immediate belief or imagination? Or opposite, wouldn't my mind be always stuck in the habits of my body with no means of escape? In Spinoza there seems to be a resulting causal determinacy in life with no real freedom of the mind or will to alter the monistic- materialistic chain of events. The Cartesian split at least allows for a freedom between mind and body, and vice versa, because there is some independence between the two. But since Descartes divided the mind from the body, or thinking from the physical world, he had to find some means for the mind to understand and act upon the body, that is, an immaterial substance relating to a material substance. He had to find a way for thought to adequately know the world of which it is separate. Since Spinoza avoids the epistemological problems of Cartesianism, as well as those of Locke's empiricism, he does not have to posit a bridge between ideas and the physical world and, thankfully, he does not have to use God as the bridge builder, as Descartes cheaply did, although Descartes later used the pineal gland to explain the link between mind and body, though this still does not explain how the immaterial can functionally relate with the material. Descartes needed some assurance that a `clear and distinct' mental idea or image is actually true in correspondence to the external reality; but Spinoza solved this problem by abandoning the Cartesian dualism of thought and extension. Descartes, by the way, declared as a Rationalist that the criteria for truth be found in the clarity and distinctness of the ideas themselves, and the fact that he also demanded some empirical verification seems a bit inconsistent. Error of true correspondence between our ideas or images and what is real in the physical world is due to hasty judgments of the will in attributing truth to our ideas of things, that is, not adequately verifying the validity of our thoughts through reason and empirical investigation. But back to Spinoza, he avoids the epistemological problem of correspondence between our ideas and the things of this world, because the ideas and the things themselves (called `ideatum') are not separate entities but the same thing (thoughtobject) viewed in different ways. Every body has a corresponding idea, which could be said to its soul, and every idea has a corresponding body-extension (ideatum) of which it is an idea. When I have an idea of something in the world, or of my own body, this idea is not something just in my mind but is in the thing itself, and the idea `I have' is not representative but is identical to the idea of the ideatum. In other words, the idea in my mind of the thing can only be the exact idea of that thing. In another sense, I am sharing in my mind the idea in the mind of that thing, though admittedly this may be a less than perfect way of saying it. There are not two ideas of something but the same idea in the eternal mode of the intellect. One really understands the reality of extended bodies through rational thought, which seems to correlate with Descartes. Spinoza, in the beginning of the third book of Ethics, denies Descartes assertion that error is caused by a free will making hasty judgments upon ideas, that is, not demanding clearness and distinctness, because error could only be due to the confused, unclear ideas themselves. We don't have a bunch of ideas that we somehow choose from as to what is clear and distinct, but instead we are constituted of ideas and if these are inadequate, that is, unclear and indistinct, then we have inadequate knowledge. The ideas themselves are already affirmations or denials, so that there is no need to posit some free will which affirms or denies. Thus for Spinoza, the inadequate ideas are cause to error, not the choosing or assertion. Since there is no freedom to affirm or deny ideas, it appears that Spinoza's view is mentally deterministic. Does this then negate any possibility for improving oneself or choosing to be more ethical? Spinoza develops his own subtle way around this problem by supposing that inadequate ideas will necessarily lead to confused action which will in turn force ideas to clear up and come closer to the truth. Inadequate ideas or confused ideas lead to inadequate, unethical action. The healthy, active mind becomes conscious of true ideas, and this is how he defines freedom of the mind. In contrast, the unfree mind is that which is passively not fully awake, so has unclear and indistinct ideas. One who thus is free and awake to reality has adequate ideas and perfected behavior. We are more free when we have more certain and adequate ideas, and this freedom is our self-determination. We are not free when affirming that 2+2=5; we are merely confused. So Descartes' contention that free will is defined by one's ability to make good or bad judgments is a false way of viewing freedom, according to Spinoza. Real freedom of the mind/body, for Spinoza, is a self-determination made from adequate ideas, since we cannot really fulfill any goal successfully in the world when holding inadequate ideas, and because this self-determination is dependent upon true ideas harmonious action will prevail, since one will then be truly and consciously united with the reality of nature. In this way, Spinoza is not fully a determinist, because he recognizes the possibility of freedom and self-determination, a freedom to clear up and `geometricanize' the mind, using deductive reasoning to arrive at adequate knowledge, which is the true corresponding thought concerning extension, so that one can live harmoniously in the world via a true knowing of it. The dualism of Descartes makes for a prejudice of the mind to treat the body and physical nature as inferior or as a soul-less, feeling-less, mechanical substance to be manipulated for mind's purposes. Personally, I don't think that manipulation of the physical has to entail a negative connotation or that all manipulation is necessarily unethical. The gymnast manipulates the body in ways the mind imagines; the landscaper manipulates nature for a mental, aesthetic purpose. Yet, if we fully believe in a radical distinction between mind and body, we (the mind) are apt to be alienated from the physical nature and treat it with little respect. We might even tend to misunderstand the body because of viewing it as a completely different other. Spinoza not only believed this ontological division of mind from body or nature was incorrect, but he also viewed this separation as unhealthy and unethical. He believed that a knowledge of the unity between mind and nature was essential to an ethical life. This is a view common to many mystical philosophies, such that one is assumed to behave in harmony with the needs of all others of their environment when the mind realizes the interconnective unity between all things and the mind is united with the world. This has a kind of romantic appeal and a kind of common sense, because mind inseparably identified with nature seems bound to behave in harmony with nature. So, Spinoza's ethical imperative is the union between mind and nature. What is not quite clear, though, is how mind, being eternally inseparable with nature, could ever have parted from nature, at least mentally. Spinoza is not prescribing that mind unite with the body or with nature, because it already is united. Instead, he seems to prescribe the realization of this union as a conscious epistemological and ethical move. It is true and good to realize this union.