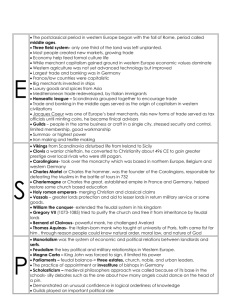

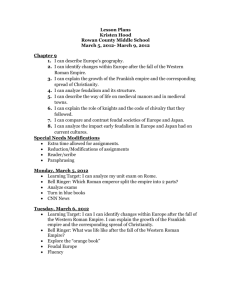

DBQ Packet for Feudalism/Manorialism

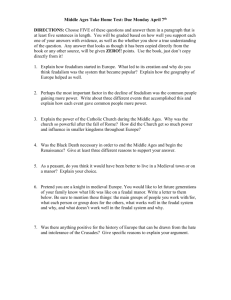

advertisement

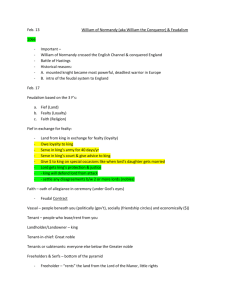

Name __________________________ Document Packet: “Feudalism” Questions: 1. Why is it important to clarify definitions before discussing or debating topics? 2. According to this information, why has it been difficult to agree on a definition of “feudalism?” Document #1 The term feudal has a curious and complicated history. All the Germanic languages had a word for cattle. As cattle were the only moveable goods of any importance among the early Germans, these words soon took the wider meaning of chattels. The Gallo-Roman language of the West Frankish state adopted such a term from the Franks and made it into "fie" or "fief." In the tenth century we find it used for arms, clothing, horses, and food. The man of wealth who kept a warrior in his household supplied him with these things. Hence when he decided to give the warrior land to support him . . . some called this land a fief. . "Fief" became "feudum" in Latin. In the seventeenth century "feodale" and "feudal" appear in France and England respectively as legal terms to refer to anything connected with fiefs and fiefholders-the medieval nobles and their lands. In 'the eighteenth century the meaning of these words was extended to cover the relations between the fief-holder and the non-noble peasants who tilled his fief. This usage appears in full force in 1789 in the famous decree of the National Assembly abolishing the "regime feodale." Today feudalism is used in these two senses and at least one other. Medieval historians in both England and the United States remain faithful to its restricted meaning-a system of fiefs and holders of fiefs . . . But continental historians frequently use it in the broader sense to cover all the political and social institutions of rural society. To them feudal society includes both knights and peasants... Finally, many modern writers have an inclination to use "feudal" to describe anything which seems to them backward. I have read in the Baltimore Sun that the Eastern Shore is feudal. SECONDARY SOURCE: Sidney Painter, Feudalism & Liberty. F. A. Cazel, ed. Baltimore. The John Hopkins Press, 1961, 3-6. Questions: 1. Why did people look to be vassals to lords such as the one mentioned below? 2. How did the lord and his vassal depend on one another? Document #2 To that magnificent lord _____ _____ Since it is known . . . to all how little I have whence to feed and clothe myself, I have therefore petitioned your piety, and your good-will had decreed to me that I should hand myself over or commend myself to your guardianship, which I have thereupon done; that is to say in this way, that you should aid and succor me as well with food as with clothing, according as I shall be able to serve you and deserve it. And so long as I live I ought to provide service and honor to you, suitably to my free condition; and I shall not during the time of my life have the ability to withdraw from your power or guardianship; but must remain during the days of my life under your power or defense. Wherefore it is proper that if either of us shall wish to withdraw himself from these agreements, he shall pay____ shillings to the other party . . . otherwise this agreement shall remain unbroken. SOURCE: Translation and Reprints from the Original Questions: 1. Why does the author describe the time that he is writing about as the “night of the ninth century?” 2. According to his account, why did feudalism, as a political system, prove necessary or useful to European society? Document #3 The night of the ninth century... What is its course? Dimly the records give a glimpse of a people scattered and without guidance. The Barbarians have broken through the ramparts. The Saracen invasions have spread in successive waves over the South. The Hungarians swarm over the Eastern provinces. "These strangers," writes Richer, "gave themselves over to the most cruel outrages; they sacked town and village, and laid waste the fields. They burned down the churches and then departed with a crowd of captives and no one said them nay. The Normans from the north penetrate by way of the rivers to the very center of France, "skimming over the ocean like pirates." Chartres, in the very heart of the realm, was wont to take pride in its name, "the city of stone," ... The Normans appear, and Chartres is sacked. William le Breton boasts the antiquity and wealth of the town of Autun; but the Barbarians have scattered these riches and its site is overgrown with weeds. "The country is laid waste as far as the Lone," says the chronicler of Amboise, so completely that where once were prosperous towns, wild animals now roam And Paris? "What shall I say of her?" writes Adrevald. "That town once resplendent in her wealth and glory, famed for her fertile lands, is now but a heap of ashes."In the course of the ninth and tenth centuries all the towns of France were destroyed. Can one imagine the slaughter and plunder concentrated in such a statement? In the little country villages the houses crumble to dust. Powerless to resist the invaders, many men-at-arms join them. They plunder together, and as there is no longer any supreme authority, private quarrels, of man against man, family against family, of district against district, break out, are multiplied, and never-ending. "And three men cannot meet two without putting them to death." "The statutes of the sacred canons (laws) . . . have become void," writes Carloman in his palace (March 884). Private wars become common. 'In the absence of a central authority," says Hariulf, "the stronger break out into violence." "Men destroy one another like the fishes of the sea"....There is no longer any trade, only unceasing terror. Fearful men put up buildings of wood only. Architecture is no more... The ties which united the inhabitants of the country have been burst asunder; customary and legal usage have broken down. Society has no longer any governance. Secondary Source: Frantz Funck-Brentano, The Middle Ages. Translated by E. O’Neill. London. Reinemann, 1922, 1-3. Document Packet: “Manorialism” Question: What distinctions between Feudalism & Manorialism are noted in this source? Document #1 Historians agree that the decline of the money economy in the late Roman Empire gave rise to manorialism and that the revival of a money economy caused its demise (decline) . . . under the manorial system a landed aristocracy controlled most of the land along with the economic, political, and legal privileges that came with such authority. The mass of the inhabitants of early medieval Europe were un-free peasants, tightly bound to the soil and to their lord's will. Though students of manorialism have long been careful to make a distinction between manorialism and feudalism, the systems are often confused and are lumped together under the term feudalism. Feudalism . . . was the political and military system which came into practice some four centuries after manorialism and which was superimposed(added to/laid over) upon it. All the men involved in feudalism were free and were generally aristocrats bound to each other by highly honorable and mutual obligations. The feudal knight followed the honorable profession of fighting; the peasant followed the unhonorable occupation of working the soil so that his master could eat. SECONDARY SOURCE: Bryce Lyon, The Middle Ages in Recent Historical Thought, 8. Question: What are some of the reasons why the manor was inefficient in medieval times? Document #2 The manor contained some forest, some land used for pasture and haying, and some cultivated land. Part of the cultivated land was reserved for the use of the lord, and the rest of it was divided among the peasants. The cultivated land of the manor was divided into hundreds of small strips, usually an acre or half an acre in size. Each peasant was assigned a number of small strips scattered over the manor. This method of dividing the land gave each peasant a portion both of the good land and the poor, but it cost him much time in going from one bit of land to another. Other farming practices were equally inefficient. The use of fertilizer and crop rotation was not understood. Each season all the cultivated land on the manor was divided into three fields, one being sown to winter crops such as wheat or rye, one to spring crops such as oats or barley, and the third being left idle that year so that it might recover its fertility. The crops yielded little even in good years. Farm animals were small and unproductive because of poor care and poor breeding. Farm implements were few and clumsy.... Medieval peasants lived in villages, which were built near the castle if the manor had One. The small thatch-roofed, one-roomed houses were grouped about an open space (the “green"), or on both sides of a single narrow street. The important buildings were the parish church, a mill, and possibly a blacksmith's shop. The population of a village might be from about one hundred to several hundred persons. SOURCE: Feudal Institutions as Revealed Question: What agricultural improvements made under the Manorial system allowed for the revival of towns & cities in the 12th & 13th centuries? Document #3 How did the three-field system work, as compared with the older . . . two-field rotation? In the eighth, ninth and tenth centuries there were only three plowings for the entire three-year cycle: winter field in October or November; summer field in March or whenever the ground was beginning to warm.; fallow towards the end of June. Thus in this earlier period a manor of 600 acres under the two-field system would plow 600 acres for 300 acres in crops, whereas the same 600 acres under the three-field system would have 400 acres under crops for the same plowing, or an increase of one-third. By the twelfth century at the latest, it had been found profitable both in the two- and three-field systems to plow the fallow twice in order to keep down weeds and to improve fertility. This change increased the advantage of the triennial rotation even further. Peasants handling 600 acres under the two-field plan, and plowing the fallow twice, would plow annually 300 + 600 = 900 acres for 300 in crops. Managing 600 acres on the three-field system, again with double plowing of the fallow, they would plow annually only 200 + 200 + 400 = 800 acres for 400 acres in crops. In terms of 600 acres, the increase of production in adopting the new rotation would still be only one-third. But since the change involved 100 acres less of annual plowing, 75 acres (plowed as 25 + 25 = 50) might be added without additional labor, if such land could be secured by reclamation. The same peasants would thus be cultivating not 600 but 675 acres (450 in crops), and their production advantage over the two-field rotation would be 50%. The spread of the triennial system thus gave a major impulse to clearing land: forests fell; swamps were drained; dikes stole polders (pieces of dry land) from the sea. The new plan of rotation, then, had several advantages. First, as has just been said, it increased the area, which a peasant could cultivate by one-eighth and it pushed up his productivity by one-half. Second, the new plan distributed the labor of plowing, sowing and harvesting more evenly over the year, and thus increased efficiency. Third, it much reduced the chance of famine by diversifying crops and subjecting them to different conditions of germination, growth, and harvest. But fourth, and perhaps most important, the spring planting, which was the essence of the new rotation, stepped up the production of certain crops which had particular significance. * * * One of the significant crops Professor White is referring to in his last sentence is oats for horses. Elsewhere in his book, Medieval Technology and Social Change, White explains why oats and horses were so important. In ancient times, most of the heavy plowing work on farms was done by oxen. Plodding oxen are much slower and less efficient than horses provided that horses can be harnessed to a plow in a way, which allows them to make full use of their pulling power. The ancients failed to develop a proper horse collar. In ancient times, the harder the horse pulled, the more the collar pressed against its upper chest and windpipe, cutting down on its oxygen supply. Put simply; in ancient times plow horses could not pull hard and breathe deeply at the same time. One of the most important inventions of the Middle Ages was a new style horse collar. It fit over the horse’s shoulders. When the animal pulled a heavy plow, the collar did not press against its chest and windpipe. The new horse collar was a big part of the medieval revolution in agriculture. Another medieval innovation was a new type of plow, the cutting edge of which turned the earth more easily and efficiently. All over Europe, when oxen were replaced by horses, when the three-field system replaced the two-field system, and when the improved plow came into general use, agricultural productivity shot up and starvation was greatly reduced. This enabled new towns to spring up and old ones to grow much larger. In these towns, other technological advances occurred which took the Middle Ages far beyond the ancients. Upon the humble but firm foundation of an innovative agriculture, the civilization of the High Middle Ages was built. SECONDARY SOURCE: “The Three-Field System,” an excerpt from Medieval Technology and Social Change by Lynn White, Jr. Illustration #1 Document Packet: “Medieval Feudal Society” (CHOOSE 2 OF THE FOLLOWING TO COMPLETE) Question: 1. How is this author’s portrayal of life in a castle different from some Hollywood productions depicting medieval life? Document #1 On the material side the life of the feudal class was rough and uncomfortable. The castles were cold and drafty. If a castle was of wood, you had no fire, and if a stone castle allowed you to have one, you smothered in the smoke. Until the thirteenth century no one except a few great feudal princes had a castle providing more than two rooms. In the hall the lord . . . received his officials and vassals, held his court, and entertained ordinary guests. There the family and retainers ate on tables that at night served as beds for the servants and guests. The chamber was the private abode of the lord and his family. The lord and lady slept in a great bed, their children had smaller beds, and their personal servants slept on the floor. Distinguished visitors were entertained in the chamber. When the lord of the castle wanted a private talk with a guest, they [both] sat on the bed. The lord and his family could have all the food they could eat, but it was limited in variety. Great platters of game, both birds and beasts, were the chief standby, reinforced with bread and vast quantities of wine. They also had plenty of clothing, but the quality was largely limited by the capacity of the servant girls who made it. In short, in the tenth and eleventh centuries the noble had two resources, land and labor. But the labor was magnificently inefficient and by our standards the land was badly tilled. Not until the revival of trade could the feudal class begin to live in anything approaching luxury. SECONDARY SOURCE: Life in a Medieval Castle. Sidney Painter, Questions: 1. Why would a knight follow the rules of chivalry? 2. What does this account tell us about medieval values in general? Document #2 During the eleventh and twelfth centuries there grew out of the environment and way of life of the feudal class a system of ethical ideas that we call chivalry: virtues appropriate to the knight or chevalier. . . . The German warriors had brought with them into the Roman Empire an admiration for the warrior virtues, courage and prowess in battle. They also valued the sound judgment that the feudal age was to call wisdom and fidelity to one's . . . word, later known as loyalty. Respect for these virtues was not a recent acquisition of the Frankish nobles. Their importance among the Germanic peoples can be clearly seen by a reader of the Norse sagas and Anglo-Saxon literature. But they were peculiarly applicable to feudal society. A man whose chief function was fighting had to be brave and effective in battle. Wisdom was a necessary attribute of the successful captain. The whole structure of the feudal system depended on respect for one's oath of homage and fidelity. These were the basic feudal virtues and formed the core of feudal chivalry. The earliest ethical ideas of the feudal class concerned their chief occupation and were designed to make war more pleasant for its participants. Armor was heavy and extremely hot under the blazing sun. No knight wanted to wear his armor when he was simply riding about, yet no knight was ever entirely safe from sudden attack by an enemy. Hence the idea developed that it was highly improper to attack an unarmed knight. You could ambush your foe, but you did not attack him until he had had time to put on his armor and prepare for battle. Then the chief purpose of feudal warfare was to take prisoners who could be ransomed. In the early days you put your prisoner in chains and dumped him in an unused storage bin under your hall. But this was highly unpleasant for the prisoner and he was likely to be the captor next time. Soon it was the custom to treat a knightly prisoner as an honored guest. The next step was to accept a son or nephew as a hostage while the captive collected his ransom. By the thirteenth century it was usual to release a captured knight on his pledge to return if he could not raise his ransom. The early tournaments were, as has been suggested, merely arranged battles. But the knights who fought in them felt it necessary to rationalize their activity. Hence they soon believed that they fought in tournaments not for amusement or to profit by ransoms but to win glory. As time went on the tournaments were carried over into actual warfare. Perhaps the high point of chivalric behavior was the return of King John of France to prison in England when he found he could not raise his ransom. One more virtue of feudal chivalry requires mention: generosity. In most societies men have admired the giver of lavish gifts, and this was a marked trait among the Germans. But this virtue assumed an unusually important place in the feudal code of chivalry. Although the concepts of feudal chivalry sprang from the feudal environment, they were popularized and made universally known by professional storytellers. The evenings dragged heavily in the gloomy castles, and knights and ladies were avid for entertainment. This was supplied by various types of wanderers. There were the tellers of . . . stories, the dancing bears, and dancing girls. But there were also those, who composed and recited long tales in verse, and minstrels who sang the compositions of others. It was through these stories that the ideas of. chivalry were spread. The livelihood of the singers and composers depended on the generosity of their patrons. Hence in their stories generosity was inclined to become the chief of all knightly virtues. SECONDARY SOURCE: Life in a Medieval Castle. Sidney Painter, Medieval Society, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1951, pp. 32-34. Questions: 1. What were some of the problems that medieval “armies” faced while in battle or attempting to organize for one? 2. Why is the author critical of fighting techniques utilized during the Middle Ages? Document #3 The feudal organization of society made every person of noble blood a fighting man, but it cannot be said that it made him a soldier. If he could sit his charger(horse) steadily and handle lance and sword with skill, the horseman of the twelfth or thirteenth century was regarded as a model of military efficiency. That discipline or tactical skill may be as important to an army as mere courage he had no conception. Assembled with difficulty, insubordinate, unable to maneuver, ready to melt away from its standard the moment that its short period of service was over, a feudal force presented an assemblage of un-soldier-like qualities such as have seldom been known to coexist. Primarily intended to defend its own borders from the Magyar (Hungarian Barbarians), the Northman, or the Saracen, the foes who in the tenth century had been a real danger to Christendom, the institution of feudalism was utterly unadapted to take the offensive. When a number of tenants-in-chief had come together, each blindly jealous of his fellows and recognizing no superior but the king - and often even the king was powerless to control his nobles - it would require a leader of uncommon skill to persuade them to institute that hierarchy(order) of command which must be established in every army that is to be something more than an undisciplined mob. . . . The radical vice of insubordination continued to exist. It was always possible that at some critical moment a battle might be precipitated, a formation broken, a plan upset, by the rashness of some petty baron . . . When the hierarchy of command was based on social status rather than on professional experience, the noble who led the largest contingent or held the highest rank felt himself entitled to assume the direction of the battle. The veteran who brought only a few lances to the array could seldom aspire to influencing the movements of his superiors. When mere courage takes the place of skill and experience, tactics and strategy alike disappear...When the enemy came into sight, nothing could restrain the western knights; the shield was shifted into position, the lance dropped into rest, the spur touched the charger, and line thundered on, regardless of what might be before it..The enemy who possessed even a rudimentary system of tactics could hardly fail to be successful against such armies. The fight of El Mansura (1250 C.E.) may be taken as a fair specimen of the military customs of the thirteenth century. When the French vanguard saw a fair field before them and the lances of the infidel gleaming among the palm groves, they could not restrain their eagerness. With the Count of Artois at their head, they started off in a headlong charge, in spite of St. Louis' (Louis IX) strict prohibition of an engagement. The Mamelukes (a warlike group of people living in Egypt) retreated, allowed their pursuers to entangle themselves in the streets of a town, and then turned fiercely on them from all sides at once. In a short time the whole "battle" of the Count of Artois was dispersed and cut to pieces.A skirmish and a street fight could overthrow the chivalry of the West, even when it went forth in great strength and was inspired by all the enthusiasm of a Crusade. SECONDARY SOURCE: The Knight in Battle. C. W. C. Oman, The Art of War in the Middle