The Third Man Phenomenon

advertisement

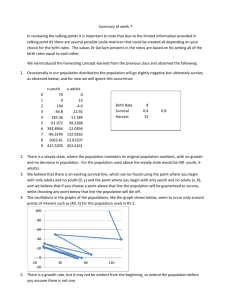

Sandra Lockwood Simon Fraser University GLS Symposium, June 2012 Third Man Phenomenon “Third Man” is the phenomenon of a “sensed presence” that appears to people who have reached the absolute limits of human endurance. It has been around since the advent of human consciousness, although the term “Third Man” is relatively recent and comes from poet T. S. Eliot, who in his 1922 poem The Waste Land wrote: Who is the third man who walks always beside you? When I count, there are only you and I together But when I look ahead up the white road There is always another one walking beside you.i Eliot is referencing the mystical experience of Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton and his two expedition teammates who each felt accompanied on their harrowing trek across the glacial “white road” of South Georgia Island. Eliot was struck by the idea, that “a party of explorers at the extremity of their strength, had the constant delusion that there was one more member than could actually be counted.”ii Shackleton’s story is one of the great epics of human survival and the best-known example of Third Man phenomena. However, his experience is not unique. Mountaineers, astronauts, athletes, sailors, and 9/11 “Twin Tower” survivors have recorded similar encounters with a life saving presence. This presence is often described as that of a guardian angel, a helper ghost, a shadow being, a heavenly guide, and a divine companion. However, you describe it, it boils down to a survival mechanism, whereby a human being in duress, in an extreme or unusual–and usually hostile–environment, is able with the help and guidance of a perceived external entity to extricate themselves from a dangerous situation, thereby saving their own life. The idea of a divine helper or angel is the backbone of many compelling survival legends. There are numerous biblical examples and historical legends–such as the battlefield “Angel of Mons” of the Great War–that can be interpreted as Third Man phenomena. As a Third Man experience is not readily explainable and cannot be qualified through any empirical study it has often been relegated to myth, dismissed as science fiction, or as a hallucinatory experience resulting from physical trauma. Because adjectives like “divine” and “heavenly” are so often attached to describe this phenomenon, it has often fallen into the category of a quasi-religious experience, and perhaps as such, it has been cast outside serious investigation. I note that Third Man experiences happen to mentally healthy individuals. The presence is not a psychotic episode. University of British Columbia psychologist Peter Suedfeld has given a lot of thought to this phenomenon. He posits that “it may be an adaptive response to an abnormal situation,” and, that he “finds no factual basis for categorizing it as a psychiatric symptom, aside from its superficial similarity to some psychiatric hallucinations.” Moreover, he adds, “it is frequently associated with successful coping.”iii Nor does Third Man have anything to do with what Psychologist J. Allan Cheyne calls the “Ominous Numinous,” the nightmarish, predatorial presence sensed by sufferers of sleep paralysis.iv A Third Man experience is not a dream, nor is it frightening. People who experience it are awake, and immeasurably calmed by its positivity in the bleakest of circumstances. What is a Third Man actually like? Sometimes it has a voice, sometimes none at all. Usually gender can be ascertained, but not always. Sometimes Third Man appears as a historical figure or a lost loved one. Most often it is grey and faceless, and manifests as no more than a feeling–an overwhelming feeling of another human presence. Moreover, Third Man is surprisingly rational and practical. The advice it intuits is invariably along the lines of “get up, eat this, stay awake, keep moving, and breathe.” An avalanche victim 2 in the Canadian Rockies described his Third Man as gently telling him to “follow the blood dripping from the tip of his nose as if it were an arrow pointing the way,” which it did, to his rescue.v Philosopher William James was one of the first to try and articulate where a Third Man comes from. In his 1958 work, The Varieties of Religious Experience, he wrote: It is as if there were in the human consciousness, a sense of reality, a feeling of objective presence, a perception of what we may call the “something there,” more deep and more general than any of the more special and particular senses.vi There is still so much we don’t know about how our minds work. Writer and medical doctor Vincent Lam writes, “ Our experiences as people may occur literally just beneath the surface of our skin, but a simple knowledge of anatomy is not sufficient to explain the everyday phenomena of consciousness or thought.”vii Human consciousness is still a frontier open to exploration. Perhaps our modern idea of consciousness traces back to René Descartes and his immortal cogito ergo sum, “I think, therefore I am.” We tend to position the mechanics of thought and consciousness in our heads, our brains. That our consciousness could live, so to speak, in other parts of our body, through our body, or even outside of our body is a foreign idea. Third Man appears to be an outward manifestation, but recent investigations suggest it to be an internal mechanism, a creation of the brain, a kind of bio-chemical switch that kicks in when the physical body is under extreme pressure. As such, Third Man may be a projection from an individual’s own mind, perhaps even the vestige of some limbic evolutionary feature for ensuring survival of the body itself. Indeed, severe physical deprivations, especially lack of oxygen and water, coupled with the effects of prolonged exposure to severe cold are almost prerequisites for triggering a Third Man experience. Isolation, and acute physical injury are other factors. It is no wonder that so many Third Man experiences occur among polar explorers and mountaineers. It is as if a switch goes off in the brain that generates an out-of-body guide to get the injured climber down from the mountain. 3 Third Man experiences typically occur in three situations: during a “Spirit Quest,” during an adventure in an extreme environment, and as a result of an accident. Spirit quests are rite-of-passage type journeys performed in some tribal cultures, such as the “walkabouts” of the Australian aborigines. They invariably involve physical isolation, deprivation and endurance. Young men embark on these quests seeking communication with a supernatural entity, a totemic spirit or an ancestor. The goal is essentially a Third Man experience. If it doesn’t happen, the quest had failed. In the second situation, the adventure, people voluntarily choose to explore remote, hostile environments. They do so for many reasons, such as scientific discovery, economic rewards, or personal motivations. In the third situation, the accident, people are thrown into a traumatic environment due to catastrophe such as a plane crash or ship wreck. I am interested in Third Man experiences as a result of adventure; I now present three examples of this intriguing phenomenon. I start with the afore-mentioned Sir Ernest Shackleton. He was an Anglo-Irish explorer, who in 1914 led the Imperial Trans Antarctic Expedition: its objective to cross the Antarctic continent from one end to the other, a feat that had not yet been done. Just before he and his 28-man crew reached the Antarctic coast their ship became trapped in an ice floe. They drifted, frozen fast in the floe for 10 months. The grinding pressure of the pack ice eventually crushed and sank their wooden boat, leaving them with what they could salvage from the wreck on the bare ice. For the next 7 months they lived out in the open, hop scotching between slabs of ice as the floe was continually opening and closing beneath them. They eventually landed on Elephant Island. However, it was uninhabited; there was no chance of rescue, as no one knew they were there. Shackleton knew they would not survive another winter. So he took a few men in a small dingy rescued for the shipwreck and made a run for South Georgia Island where he knew there was a whaling station. The Southern Ocean is notorious as the most dangerous water on earth. Miraculously, they crossed 800 miles of it in hurricane conditions in an open boat, to arrive at South Georgia, but on the side opposite to the location of the whaling station. They then trekked overland–an unimaginable awful journey–across crevasse-strewn 4 glaciers and mountainous terrain. They staggered into the whaling station barely recognizable as men. Against the greatest odds, they survived, and their survival ensured the rescue of the remaining men stranded on Elephant Island. Shackleton, in his account of the ordeal, revealed that a mysterious companion had given him strength. He wrote “During that long and racking march of 36 hours over the unnamed mountains and glaciers of South Georgia, it seemed to me often that we were four not three.”viii So uncomfortable was he of this admission, he scratched it from his first draft. However, upon learning that both his teammates, independent of and unknown to his own experience, had also felt the presence of another man, he added it back in. Shackleton did not know how to interpret his experience. Antarctica is an alien place. He recognized the visual tricks of the landscape. He recounted the experience of an unusual iceberg that appeared to all his crew as “an Antediluvian monster, an icy Cerberus” that appeared to weep from its eyes as its head lolled up and down in the icy swells.ix He wrote: This may seem fanciful to the reader, but the impression was real to us at the time. People living under civilized conditions, surrounded by Nature’s varied forms of life and by all the familiar work of their own hands, may scarcely realize how quickly the mind, influenced by the eyes, responds to the unusual and weaves about it curious imaginings…. We had lived long amid the ice, and we halfunconsciously strove to see resemblances to human faces and living forms in the fantastic contours and massively uncouth shapes of berg and floe.x Shackleton was a rational man: his Third Man experience defied comprehension and his reluctance to discuss it never left him. He told the London Daily Telegraph, “There are some things which never can be spoken of. Almost to hint about them comes perilously close to sacrilege.”xi Shackleton shared this reluctance with aviation pioneer Charles Lindberg who kept silent about his own Third Man experience for over 30 years. Lindberg was the American aviator who, in 1927, piloted his monoplane, the Spirit of St. Louis, from New York to 5 Paris. It was the first non-stop transatlantic solo flight. It was a bitterly cold, grueling 33hour feat of endurance. After a lightening storm upset his compass bearings, Lindberg had to navigate by stars. He then flew through heavy banks of fog, so disorientating that he could not tell sea from sky. He sometimes found he was flying so close to the water that icy spray from the ocean splashed his cockpit windows. The unremitting drone of the engine and wind enveloped him, further dulling his senses. About 22 hours into the flight, fighting exhaustion, and freezing stiff from being trapped in his seat, he had the overwhelming sensation that he was not alone. He recounts in his memoir: When I’m staring at the instruments during an unearthly age of time, both conscious and asleep, the fuselage behind me becomes filled with ghostly presences–vaguely outlined forms, transparent, moving, riding weightless with me in the plane. These phantoms speak with human voices… they are friendly, vapor-like shapes… I feel no surprise at their coming… without turning my head I see them as clearly as though in my normal field of vision.”xii They stayed with him until the coast of Ireland came into view, and he was able to orient himself and fly safely on to Paris. Although Lindberg published an account of his voyage upon returning to the States, like Shackleton, he wrestled with his Third Man experience, not divulging it until 1953 in an interview published in the Saturday Evening Post: I’ve never believed in apparitions, but how can I explain the forms I carried with me through so many hours of this day? Transparent forms, in human outline– voices that spoke with authority and clearness–that told me–that told me–but what did they tell me? I can’t remember a single word they said.xiii The forms kept him awake, preventing him from plunging into the sea. Perhaps Lindberg didn’t remember because what they said because it was unnecessary to his survival. In contrast, climbing legend Reinhold Messner remembers exactly the advice imparted to him as he lay near death just under the summit of Mount Everest. Messner is the prototype for the Twentieth century version of the “extreme athlete,” seeking transcendence through punishing physical challenges. He is a record holder of 6 many mountaineering “firsts,” including being the first to climb Everest solo and without bottled oxygen, and first to climb all the “Eight-Thousanders,” as the 14 highest peaks on Earth–all above 8000 meters–are known. During his 1980 solo climb of Everest, Messner had a particularly vivid Third Man encounter. Unlike many Everest expeditions which resemble military operations with armies of Sherpa helpers, Messner practiced the “Alpine style” of climbing, taking only what he could carry on his back, and eschewing oxygen tanks as he considered their use “unsporting.” This gave him no margin for error, and mistakes are easily made when the brain is starved of oxygen. Messner was sitting practically catatonic in his last bivouac before his summit push. He was severely hypoxic and dehydrated, unable to think straight, unable to light his small cooker to melt snow for fluid or prepare an essential hot meal. At this height, speed is of the essence. Human being can stay a maximum of 48 hours above 8000 meters, in what mountaineers call the “Death Zone” before the body shuts down. Messner recounts: ‘Fai la cucina’ says someone near to me, get on with the cooking. I think again of cooking. Half aloud I talk to myself. The strong feeling I have had for several hours past, of being with an invisible companion has apparently encouraged me to think that someone else is doing the cooking. I ask myself too, how we shall find space to sleep in this tiny tent. I divide the piece of dried meat, which I take out of the rucksack into two equal portions. Only when I turn round do I realize that I am alone.xiv Messner particularly remember the words of his companion because it spoke to him in Italian. His native tongue is South Tyrol German, and for the past three months he had been speaking only English with his American girlfriend. He obeyed the orders of his invisible Italian companion and made himself a meal. A few hours later he was able to summit Everest and begin his descent. This was not his first experience with a Third Man encounter and he knew to take its advice. In Messner’s interpretation, “The body is inventing ways to let the person survive.”xv Already from these three examples, we can deduce some common elements of Third Man encounters. Isolation is apparent; we human beings are social creatures and seek the 7 company of others. We react poorly to long stretches in solitary conditions. Although Shackleton and his teammates were a group of three, they might have well have been on the moon they were so far removed from civilization. Lindberg and Messner were both completely alone, and both aware should they fail, that they were unreachable. John Geiger in his book The Third Man Factor, considers what he calls the “Angel Switch,” a reaction in the brain to literally “turn on another person.” xvi He writes,” [A] benevolent being exists not outside of us but within. It is a real power for survival, a secret and astonishing capacity of mind, part of our social hardware.” xvii The switch turns on and conjures another person thus alleviating the painful isolation. Moreover, this conjured “other” seems to be the rational one, able to make decisions and take action. In Lindberg’s case, he felt his phantoms were navigating the plane. In each of these three examples, the men were cold and exhausted. Shackleton and his men were suffering the effects of prolonged exposure, dehydration, starvation, frostbite and scurvy. Messner was suffering from acute hypoxia. One key factor in Lindberg’s ordeal was the visual monotony of his environment: the grey sky, the grey sea, the banks of fog that obliterated the horizon, coupled with the auditory drone of wind and engine. Lack of stimuli, or the persistent assault of stimuli on the senses, is in itself very isolating. Peter Suedfeld has combed through countless Third Man experiences in his research. He deduces: The reliable antecedent conditions [to a sensed presence] seem to involve variables of monotony, isolation, and ambient cold. Contributing factors include physical debilitation, sleeplessness, exhaustion, and the cognitive/affective variables of fear, perceived danger and uncertainty. xviii Another factor, albeit a nebulous one, is the will to survive. This “will” seems to predicate a receptiveness to heed the otherworldly advice of a Third Man. A fierce determination to triumph in the cruelest elemental circumstances is also crucially important. Shackleton had not just his life on the line but also the lives of his entire crew; he knew he had to succeed. However, Claude Piantadosi, a scientist of the Biology of Human Survival, reserves some skepticism. He notes: 8 Strength of spirit, motivation, and psychological factors are very important for survival but are less decisive under truly catastrophic conditions than our poets and writers would like us to believe. To state it plainly, rarely does one person survive under extreme conditions when another dies simply because the survivor has a greater will to live.xix With due regard to Piantadosi, the poet in me is moved by the magical power of this inexplicable presence that comes to encourage survival. I am certain one day science will reduce Third Man down to its biochemical components, but that hasn’t happened yet. So Third Man still rests in that spooky grey area of things human, we humans don’t yet understand about being human. ii Eliot, T.S., The Wasteland and Other Poems. London: Penguin Classics, Reprint edition, 2003. 77. Print. Eliot , T.S., quoted in John Geiger, The Third Man Factor. New York: Weinstein ii Books, 2009, 42. Print. iii Suedfeld, Peter, and Jane Mocellin. “The ‘Sensed Presence’ in Unusual Environments.” Environment and Behavior 19:33 (1987): 49. Web. iv Cheyne, J. Allan, “Ominous Numinous,” Journal of Conscious Studies, 8, No. 5–7, (2001) 134. Web. v Geiger, John, The Third Man Factor. New York: Weinstein Books, 2009. 8. Print. 9 James, William, The Varieties of Religious Experience. New York: Longman, Green vi and Co., 1916. Web. vii Lam, Vincent. quoted in John Geiger, The Third Man Factor. xiv. viii Shackleton, Ernest, South, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1998. Shackleton, Ernest. “South” Ice: Stories of Survival from Polar Exploration. Willis, ix Clint, Ed., New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1999. 270. Print. x Ibid. 270. xi Daily Telegraph, London 1 Feb. 1922. xii Coffey, Maria, Explorers Of The Infinite. New York: Tarcher, 2008. 185. Print. xiii Lindberg, quoted in John Geiger, Third Man Factor. 87. xiv Messner, Reinhold. The Crystal Horizon. Trans. Jill Neate & Audrey Salkeld. Ramsbury: Crowood Press, 1989. 224. Print. xv Messner, Reinhold, quoted in John Geiger, Third Man Factor. 240. xvi Geiger, John. 237. xvii Ibid. 240. xviii Suedfeld, Peter, and Jane Mocellin. 49. xix Piantadosi, Claude A.. Biology of Human Survival: Life and Death in Extreme Environments. North Carolina: Oxford University Press, 2003. p 4. Web. 10