Final Report of National Ice Taskforce 2015

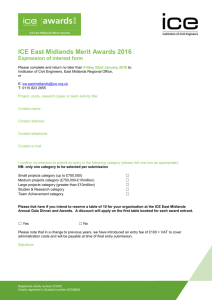

advertisement