A2.1.3.TestGenes - Life Science Academy

advertisement

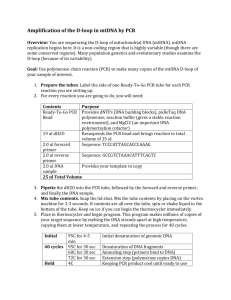

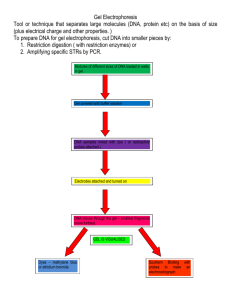

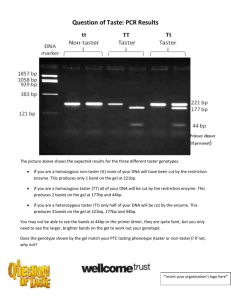

Activity 2.1.3 Test Your Own Genes Introduction Aaron and Gina Smith decide to have genetic testing to determine if they are carriers for cystic fibrosis. They both feel this is information they need to know before they make decisions about having children. Results reveal that neither Gina nor Aaron is a carrier for the disease. Relieved to know they can not pass cystic fibrosis to their child, the couple begins plans for their new family. Multiple tests and interventions are available to test and screen our DNA. In this lab, you will experience one method of looking inside of our cells and decoding the message buried in the sequence of nucleotides. The genotype, what is written in our DNA, predicts phenotype, what we see as a result of that code. This genotype may relate to a simple trait, such as eye color, or presence of dimples, or, unfortunately, may signal the presence of an incurable disease. Amazingly, all humans share 99.9% of their genetic code. It is the remaining 0.01% that actually makes us unique individuals. This small percentage controls aspects of our appearance, our personality, and even our health profile. The parts of the human genome that vary by just a single nucleotide are referred to as single nucleotide polymorphisms (abbreviated SNPs and pronounced “snips”). If these SNPs occur in a non-coding region of the genome, you would not even know they are there; however, SNPs in an important gene can lead to variation in traits or even disease. Remember that a change in DNA can lead to a change in a protein. If the protein plays a role in keeping you healthy, serious consequences may occur. Tests to locate these SNPs can pinpoint disease genes and provide medical options. In the 1930s, scientists first studied a genetic basis to taste. While synthesizing a chemical called phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) in his lab, scientist Arthur Fox accidentally released some into the air. Fox’s colleague in the lab complained that the dust had a very bitter taste. Fox, however, tasted nothing. After further studies, scientists concluded that the inability to taste PTC is actually a recessive trait. Bittertasting compounds are recognized by receptor proteins on the surface of taste cells. The gene for this PTC taste receptor, TAS2R38, was identified in 2003. Sequencing identified three variations in this gene from person to person. These base pair differences, or SNPs, correlate to a person’s ability to taste PTC. In this lab, you will evaluate one of these SNPs, examine your own DNA sequence and determine your own genotype. Then using a strip of PTC paper, you will determine how well this genotype predicts your phenotype – your ability to taste PTC. This type of genome screening allows individuals to pinpoint SNPs and to use this genetic information to prevent and treat disease, as well as design new drugs tailored to your own genetic profile. But more on that later! In this activity, you will have a chance to complete genetic testing on your own DNA. Using the techniques of molecular biology you have learned in the PLTW Biomedical Sciences courses, you will isolate your own DNA, amplify a specific gene using © 2010 Project Lead The Way, Inc. Medical Interventions Activity 2.1.3 Test Your Own Genes – Page 1 PCR, digest this DNA into fragments using restriction enzymes, and finally use gel electrophoresis to visualize your results. Gel results will provide information on your genotype. You will then be able to test your phenotype and see the connection between your genes and their expression. Equipment Computer with Internet access Laboratory journal Thermal cycler Carolina’s Using a Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) to Predict Bitter Tasting Ability Lab Kit (with 0.2ml PCR tubes) o Chelex resin o PTC primer/loading dye mix o PCR beads o DNA marker and HaeIII restriction enzyme o PTC taste and control strips Highlighter Agarose TBE buffer CarolinaBLU™ stain 0.9% saline solution Micropipettors and tips Microcentrifuge 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes Microcentrifuge tube rack 0.2ml PCR tubes Electrophoresis chamber and power supply White light box Paper cup Permanent markers Water bath (99°C) Forceps Ice bucket and ice Vortex (optional) Procedure Part I: Overview of the Lab 1. Carefully read the procedure for the entire activity. 2. In your laboratory journal, write an objective for this experiment. Underneath the objective, list the main laboratory steps that are necessary to achieve your objective. Clearly describe the goal of each step. 3. Draw a flow chart in your laboratory journal or use Inspiration software to track the DNA/gene of interest. Pay attention to the role of SNPs in your analysis. Show how each step of the lab will help you make your final conclusion about your own genotype and phenotype. © 2010 Project Lead The Way, Inc. Medical Interventions Activity 2.1.3 Test Your Own Genes – Page 2 Part II: Isolate Your DNA Before you can amplify the gene responsible for PTC tasting ability, you will need a sample of your own DNA. Carefully extract a sample of your DNA from your cheek cells. Remember – you do not want to contaminate your sample. This will be the starting material for your PCR reaction. 4. With a partner, brainstorm how you can isolate DNA from your own cheek cells. Thinking about where DNA is located in the cell, describe what has to happen for you to isolate cells and release the DNA from these cells. Write down your ideas in your lab notebook and discuss your ideas with the class. 5. Use a permanent marker to label a 1.5ml microcentrifuge tube with your initials. Place this tube aside for the moment. 6. Pour all of the saline solution (0.9% NaCl) into your mouth and vigorously swish the liquid around for thirty seconds. 7. Gently expel the liquid back into the paper cup. 8. Swirl the cup gently to mix the cells and then use a micropipettor to transfer 1000µl of the solution to the labeled microcentrifuge tube. 9. To pellet all of the cells in the liquid, place your tube in a balanced centrifuge and spin at full speed for 90 seconds. 10. Carefully pour off the supernatant, the liquid at the top, into the paper cup. Try to remove most of the supernatant without disturbing the pellet of cells at the bottom of the tube. 11. Set a micropipettor to 30µl. Place a fresh tip on the micropipettor and place the tip into the microcentrifuge tube containing your cells. 12. Gently pipet up and down to resuspend the cells in the liquid. Be careful not to generate bubbles. 13. Withdraw 30µl of the solution and add it to a microcentrifuge tube containing 100µl of Chelex®. Label the cap and the side of the tube and make sure the cap is on snugly. 14. Follow your teacher’s instructions to heat your tube for 10 minutes in a boiling water bath. 15. Use a forceps to carefully remove the tube from the water bath. 16. When cool to the touch, vortex or shake the tube vigorously for five seconds. 17. Centrifuge the tube again at full speed for 90 seconds. 18. Transfer 30µl of the clear supernatant to a clean, labeled 1.5ml tube. Be careful not to transfer any of the cell debris to this tube. 19. Answer conclusion question 1. Part III: Amplify Your DNA by PCR Now that you have a sample of your own DNA, you will use PCR to target and amplify the gene we will be working with in the lab. The gene of interest in the experiment, TAS2R38, is located on chromosome #7. This gene is associated with our ability to © 2010 Project Lead The Way, Inc. Medical Interventions Activity 2.1.3 Test Your Own Genes – Page 3 taste a chemical called PTC. Primers specific to a 220-bp sequence in this gene will be used to make millions of copies for our study. 20. Obtain a PCR tube containing a Ready-to-Go™ PCR bead. Label the tube with your name or initials. Recall from the previous experiment the reagents that are included in this bead. 21. Add 22.5µl of PTC primer/loading dye mix to the tube. Place the tube on ice and allow the bead to dissolve. The primer/loading dye mix will turn purple as the PCR bead dissolves. 22. Use a micropipettor with a fresh tip to transfer 2.5µl of your cheek cell DNA (from Part I) directly into the primer/loading dye mix. 23. Gently tap the tube on the desk or lab bench to assure that all liquids are pooled at the bottom of the tube. 24. Place the PCR tube back on ice until you are ready to load your sample into the thermal cycler. 25. Place your PCR tube, along with other student samples, in a thermal cycler that has been programmed for 40 cycles of the following protocol. The profile may be linked to a 4°C hold program after the cycles are completed. o Denature at 94°C for 30 seconds o Anneal at 64°C for 45 seconds o Extend at 72°C for 45 seconds 26. Copy the PCR protocol down in your laboratory journal. Referring to this specific lab experiment, describe what is happening in the tube at each temperature. 27. After cycling, store the amplified DNA on ice or at -20°C until you are ready to move on to Part IV. Part IV: Digest PCR Products with Restriction Enzyme HaeIII Restriction enzymes, molecular scissors, recognize specific DNA sequences and cut the nucleotide strands. In this part of the experiment, you will use a specific restriction enzyme, HaeIII, to identify SNPs or base pair differences in the amplified segment of the PTC tasting gene. Since DNA codes for the production of proteins, changes in the sequence can lead to differences in the protein – in this case, the receptor that attaches to the chemical and allows us to taste PTC. 28. Observe the DNA sequences of a “nontaster” and a “taster” shown below. NOTE: This is only a region of the 220bp PCR product – a region that contains a SNP. NONTASTER (tt) TASTER (TT) GGCGGGCACT GGCGGCCACT CCGCCCGTGA CCGCCGGTGA 29. Draw the sequences in your laboratory journal. Note any differences using a highlighter. © 2010 Project Lead The Way, Inc. Medical Interventions Activity 2.1.3 Test Your Own Genes – Page 4 30. In your laboratory journal, show how the two sequences of amplified DNA would be affected by digestion with the enzyme HaeIII. This enzyme recognizes the DNA sequence 31. Note that the line above shows exactly where the restriction enzyme makes its cut. Notice that HaeIII cuts DNA evenly down the strand and leaves even edges, referred to as blunt ends. Other enzymes, such as EcoRI, the enzyme you used in your DNA Detectives lab in HBS, cut DNA unevenly, leaving jagged edges called sticky ends. 32. In your laboratory journal, describe how the enzyme would cut in a taster and in a nontaster. How many fragments would be produced in each case? Draw or explain how this product would be verified using gel electrophoresis. 33. Predict what you would see on a gel if you were a heterozygous Tt taster. 34. Discuss your predictions with the class. 35. Label two clean 1.5ml microcentrifuge tubes. One tube should be labeled as “Undigested” and the other labeled as “Digested.” Both should display your name or initials. 36. Transfer 10µl of your PCR product to the “Undigested” tube. Store this sample on ice until you are ready to begin Part V. 37. Transfer the remainder of your PCR product (approximately 15µl) to the “Digested” tube. 38. Pipet 1µl of the enzyme HaeIII directly into the PCR products in the “Digested” tube. Mix by pipetting up and down. NOTE: This is a tiny volume. Make sure you see the drop of restriction enzyme enter the tube. 39. Mix and pool the reagents by pulsing them briefly in a microcentrifuge or by gently tapping the bottom of the tube on the lab bench. 40. Incubate the tube in a 37°C water bath or in the thermal cycler set to 37° for one hour. 41. Remove the sample from the heat source and store it on ice or in the freezer until you are ready to complete Part V. 42. If instructed to do so by your instructor, prepare a 6-well, 30ml, 2% agarose gel. Store the solidified gel at 4°C. You will share a gel with another student. Part V: Analyze PCR Products by Gel Electrophoresis Now that you have digested your sample of DNA with the restriction enzyme, you will use electrophoresis to view your results and predict your genotype. 43. Place the solidified gel in the electrophoresis chamber and add enough 1X TBE buffer to cover the surface of the gel. 44. Carefully remove the comb. Make sure that the wells are submerged. If necessary, add additional TBE buffer. 45. Using a fresh tip for each sample, load the following onto your gel: © 2010 Project Lead The Way, Inc. Medical Interventions Activity 2.1.3 Test Your Own Genes – Page 5 o o o o o Lane 1 – pBR322/BstNI DNA Marker – 20 µl Lane 2 – Student 1 Undigested DNA – 10µl Lane 3 – Student 1 Digested DNA – 15µl Lane 4 – Student 2 Undigested DNA – 10 µl Lane 5 – Student 2 Digested DNA – 15µl 46. Copy your gel loading diagram into your laboratory journal. Make sure you know the location of your own DNA. 47. Run the gel at 130V for 30 minutes or until the dye front has moved almost to the end of the gel. 48. Stain the gels according to your teacher’s instructions. This part may be completed for you. 49. View the gel using a white light box. Part VI: Determine Your PTC Genotype and Phenotype. 50. Observe the bands on your gel or in a photograph of your gel. 51. Locate the lane containing the DNA markers. Working from the well, locate the bands corresponding to each restriction fragment: 1857bp, 1058bp, 929bp, 383bp, and 121bp. The 1058bp and 929bp fragments will be very close together and may appear as a single band. The 121bp may be very faint or not visible. 52. Locate the lane containing the undigested DNA fragment. Using the bands of the DNA marker, confirm that the undigested PCR product corresponds with a size of about 221bp (the size of the fragment you amplified). 53. In your laboratory journal, describe what you would see on the gel if a person was a tt nontaster (homozygous recessive), a TT taster (homozygous dominant), or a Tt taster (heterozygous). Relate what you would expect to see to SNPs and the restriction digest. 54. Now compare your digested DNA to the uncut control and determine your own genotype. 55. Describe your findings in your laboratory journal. Predict whether or not you will be able to taste PTC. 56. Obtain one strip of control taste paper from your teacher. 57. Place the control strip on your tongue for several seconds. Note the taste in your laboratory journal. 58. Remove the control paper and dispose of it in the appropriate waste receptacle. 59. Obtain a PTC taste paper from your teacher and place it in the center of your tongue for several seconds. 60. In your laboratory journal, describe the taste of the PTC paper. Compare the taste to that of the control. Is the taste strongly bitter, weakly bitter, or the same as the control paper? 61. Correlate your PTC genotype with your phenotype. Do they match up? 62. Tally classroom data in a table as shown below: © 2010 Project Lead The Way, Inc. Medical Interventions Activity 2.1.3 Test Your Own Genes – Page 6 Phenotype Genotype Strong Taster Weak taster Nontaster TT (homozygous) Tt (heterozygous) tt (homozygous) 63. Read the Genetic Science Learning Center article PTC: Genes and Bitter Taste at http://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/begin/traits/ptc/. Use this information to help you interpret your results and answer the remaining Conclusion questions. Conclusion 1. In the first part of the DNA isolation, you discarded the supernatant and kept the cells. However, after processing the sample with Chelex®, you kept the supernatant and discarded the pellet. Tracing the path of your DNA, explain the goal of each processing step. 2. Explain how the HaeIII enzyme discriminates between the C-G polymorphism in the TAS2R38 gene. 3. According to the class results, how well does your genotype predict PTC-tasting phenotype? Considering that not everyone who can taste PTC tastes it the same way, what does this tell you about classical dominant/recessive inheritance? 4. Using what you know about genetics, SNPs, and the PTC gene, explain why it is possible for a person to be a “weak taster.” 5. Some studies have shown that PTC “tasters” are less likely to become smokers. Why do you think scientists are seeing this correlation? 6. How can the techniques described in this lab be used to test for human disease genes? Would this type of testing work on every disease with a genetic component? 7. What ethical issues are raised by human DNA typing experiments? © 2010 Project Lead The Way, Inc. Medical Interventions Activity 2.1.3 Test Your Own Genes – Page 7