Neonatal Resuscitation in the Gray Zone of Viability

advertisement

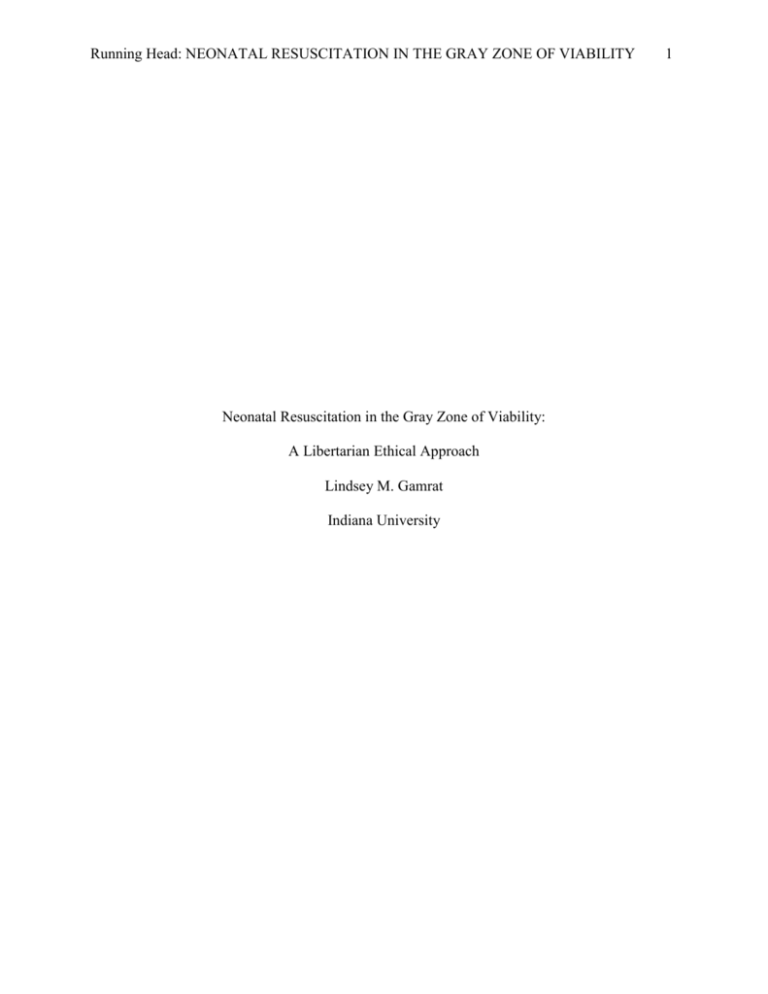

Running Head: NEONATAL RESUSCITATION IN THE GRAY ZONE OF VIABILITY Neonatal Resuscitation in the Gray Zone of Viability: A Libertarian Ethical Approach Lindsey M. Gamrat Indiana University 1 NEONATAL RESUSCITATION IN THE GRAY ZONE OF VIABILITY 2 Advances in science and medicine have the potential to bring great progress to society but not without raising new ethical questions along the way. Progress in the technology of neonatal resuscitation and intensive care has been no exception. Over the past several decades, saving infants of lower and lower gestational ages has been made possible as the medically accepted limit of viability has been pushed back (Bhatia, 2006; Donohue, Boss, Shepard, Graham, & Allen, 2009; Doroshow et al., 2000; Kuschel & Kent, 2011; Krug, 2006; Seaton, King, Manktelow, Draper, & Field, 2013; Singh et al., 2007; Stephens, Tucker & Vohr, 2010; Sudia-Robinson, 2011). Technology can only go so far, and this has created a “gray zone” when defining a truly viable infant. When an infant is born into this category, decisions must be made about the best course of action. There is no sharp limit that can distinguish a late term miscarriage from a viable preterm infant (Zayek et al., 2011). A libertarian ethical approach to this issue would need to consider the extent of the personal rights of those involved in making these decisions: the physician, the parents, and the infant. By applying the concepts of selfliberty and noninterference of rights, an ethical solution can be proposed to resolve the issue of whether or not an infant at the edge of viability should be resuscitated or allowed to die and who gets to make this decision. Viability can be defined in basic terms as “the ability to work, function, or develop adequately” (Zayek et al., 2011, p. 130). Current medical professionals expand on this definition to explain that the limit of viability is the fetal age associated with a 50% chance of long-term survival outside of the womb (Zayek et al., 2011). The boundaries of this limit are not clear, and a “gray zone” exists within which a drastic differing of opinions and projected prognoses occurs. This gray zone of viability is generally described between 23 and 24 weeks gestation or 400-500 NEONATAL RESUSCITATION IN THE GRAY ZONE OF VIABILITY 3 grams birth weight (Bhatia, 2006; Kuschel & Kent, 2011; Ramsay & Santella, 2011; Seaton et al., 2013; Sexson, Cruze, Escobedo, & Brann, 2011; Singh et al., 2007; Stephens et al., 2010; Sudia-Robinson, 2011; Zayek et al., 2011). Resuscitation of an infant born at the edge of viability can be a massive moral dilemma for the parties involved. There is no governmental mandate that states an infant must be resuscitated in all situations (Sexson et al., 2011). Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP) guidelines state that it is acceptable to withhold resuscitation in some cases on the grounds of futility (Sexson et al., 2011). This statement is vague in practice as futility cannot be certain in many cases. The absence of true guidelines means that it is up to those involved in each specific situation to determine whether resuscitation will take place. Unfortunately this decision is usually made in a time of crisis where little thought has been placed on the issue up to the point of extremely preterm labor. The main parties involved in the situation usually include the physician, the parents of the infant, and the infant itself. All three represent different viewpoints and are governed by their own rights and moral frameworks. The principle of beneficence in medical practice implies that a physician should act out of the best interest of his or her patient (Doroshow et al., 2000). Beneficence is typically the driving force behind resuscitation due to the fact that best interest and remaining alive are often thought of as interchangeable. A physician may also fear that if they do not resuscitate but the infant does not die, he or she has potentially been exposed to a prolonged period of hypoxia (Krug, 2006). This idea of nonmaleficence or “to do no harm” combined with beneficence compels most physicians to believe that it is their job to resuscitate an infant born in the gray zone of viability (Doroshow et al., 2000; Krug, 2006; Sudia-Robinson, 2011). However, this sense of duty felt by physicians does not always consider the rights of the parents and of the infant. In fact, Singh et NEONATAL RESUSCITATION IN THE GRAY ZONE OF VIABILITY 4 al. (2007) found that only one third of neonatologists stated that the parents’ wishes would influence their choice whether or not to resuscitate. This discrepancy has led to various lawsuits such as Miller v. HCA where a hospital policy to resuscitate was initiated despite the parents’ clear wishes against resuscitation and refusal to sign a resuscitation consent form. The Miller’s baby girl was resuscitated and lived, but with profound physical and mental handicaps (Hurst, 2005; Krug, 2006). Libertarians would disagree with government involvement in this issue claiming that government mandates infringe upon the rights of the parents to choose what is best for their child. Physicians may argue that parents are not able to determine what is best for the infant as their judgment is likely clouded by anger, guilt, grief and other negative emotions (Catlin, 2005; Doroshow et al., 2000). Most physicians claim to base the decision to resuscitate and estimation of prognosis on the appearance of the infant at birth despite these methods proving to be largely unreliable (Bhatia, 2006; Kuschel & Kent, 2011; Singh et al., 2007). Bhatia (2006) states that the evaluation of the infant in the delivery room is “speculation at best” (p.525). In reality, the right of the parents to make an informed decision could be protected if physicians would provide prenatal education on the limits of viability, prognoses of extremely premature infants, and treatment options in these situations. There is no mention of including viability education to parents in prenatal education guidelines (Catlin, 2005; MacDonald, 2002; Sudia-Robinson, 2011). If parents were educated on this matter, they could begin to think about what their decision would be if faced with the situation of an infant born between 23-24 weeks. Ideally, they could make decisions in advance and some ethicists have suggested forming some sort of advance directive for neonates (Doroshow et al., 2000; Kuschel & Kent, 2011; Sudia-Robinson, 2011). The libertarian perspective would encourage viability education for parents so that they NEONATAL RESUSCITATION IN THE GRAY ZONE OF VIABILITY 5 are better equipped to use their right to make decisions for their own child. The physician’s role is to educate parents and perhaps guide them in making choices for the infant based on clinical expertise and experience. In the end though, it is not the right of the physician to make decisions for someone else’s family. Parents can be assumed to have the best interest of their child in mind, and in the absence of the baby’s ability to make decisions, parents are the natural surrogates (Doroshow et al., 2000; Singh et al., 2007). Parents have a right to be adequately informed to give or refuse consent to treatment when the outcome is questionable. This is again where prenatal education comes in to play. Unfortunately, the only mention of preterm birth that many parents receive is through media. This can cause parents to have a skewed perception of reality because the only stories that make it in to the news are the stories of “little miracles” and survival against all odds (Catlin, 2005; Kuschel & Kent, 2011). Parents need to know the actual statistics of survival and survival without impairment when considering options for their child. Catlin (2005) discusses the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology’s view that “presents women’s autonomy as the overriding principle of decision making” (p. 172). Catlin further describes other feminist ethical views on neonatal resuscitation, and libertarians would likely agree with these interpretations. Catlin quotes a conclusion drawn after a review of ethical principles stating that “despite beneficence owed to the fetus, the principle of maternal autonomy must be upheld and that a woman’s wishes about fetal or newborn treatment must be respected” (p. 172). Parents have many factors to consider when deciding on treatment for their newborn such as the financial burden of neonatal intensive care, the possibility of lifetime care, as well as the stress and emotional cost to their family. It is not the place of the physician, hospital policy, or government mandates to make such important decisions for the family of these extremely premature infants. NEONATAL RESUSCITATION IN THE GRAY ZONE OF VIABILITY 6 When considering the issue of whether or not to resuscitate an infant born at the edge of viability, the libertarian ethicist would not forget to consider the rights of the infant as well. The Born Alive Infants Protection Act of 2002 states that any infant born breathing, with a beating heart, pulsation of the umbilical cord or movement of voluntary muscles is a person entitled to protection of the law (Hurst, 2005). This act does not cover infants who are born not breathing or without a beating heart though, and the NRP guidelines have not been altered as a result of this act. Instead, it is suggested that the infants who are not resuscitated be treated with comfort care measures (Hurst, 2005). Infants who receive treatment in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) are often subjected to pain and suffering (Doroshow et al., 2000; Krug, 2006; Singh et al., 2007). Oftentimes, resuscitation and intensive care of an infant of questionable viability is not saving the infant’s life but instead prolonging death and extending periods of suffering (Bhatia, 2006; Donohue et al., 2009; Sudia-Robinson, 2011). A busy NICU does not seem the ideal place to die. When choosing comfort care over resuscitation, an infant is allowed to die warm and comfortable in his or her mother’s arms. Just because the choice has been made not to resuscitate does not mean that there is not any care provided for the infant. “Care” is not discontinued, only technical interventions and advanced life support. The dying infant should still be treated with compassion, dignity, and have their needs met (MacDonald, 2002; Sexson et al., 2011). Quality of life is another issue that needs to be addressed when assessing whether or not to resuscitate an infant (Bhatia, 2006; Doroshow et al., 2000; Kuschel & Kent, 2011; Stephens et al., 2010). The majority of infants who are born between 23 and 24 weeks and survive are faced with severe disabilities and diseases including chronic lung disease, central nervous system damage, retinopathy/blindness, and other special health care needs (Stephens et al., 2010). Many of these children will require a lifetime of care, and it is the family who must NEONATAL RESUSCITATION IN THE GRAY ZONE OF VIABILITY 7 deal with paying for and/or performing this care. In many cases the child will need a surrogate for their entire life, so parents as natural surrogates should not be denied decision making privileges in the beginning of life. Libertarians would recognize the right of an infant to receive comfort care and be free from pain and suffering, but ultimately the rights of the parents would prevail as the main authority in decision making. By considering the extent of rights allotted to all of the parties involved, a libertarian solution can be proposed to resolve the issue of determining resuscitation measures of an infant born on the border of viability. This solution to the problem would vary by case; as each case would present with different individuals of varying circumstances being treated by different physicians. That being said, it is not the place of the government to impose paternalistic laws and guidelines to make these decisions and take away the right of the parents to choose what is best for their child and for their family. While some may argue that is not moral to choose anything but whatever means necessary to give an infant a chance at life, it is not the place of the government to impose moral legislation. Infants have the right to be free from undue suffering and to have someone who loves them and cares about their family as a unit make the best decision for them. Donohue et al (2009) suggests a “gold standard” for decision making in these cases that is “a collaborative one that balances physician, parent, and fetal/infant concerns” (p.906). The physician’s role is to inform the parents of facts that may influence their decision including survivability statistics, possibility of co-morbidities, and personal experiences relating to outcomes in the specific area of practice. Ideally, this information will be presented to parents prenatally so that they may begin to think about the issue and their beliefs before a time of crisis. The parents should discuss their thoughts with the physician so that everyone is clear in advance on the course of action. Of course the circumstance will be assessed at the time of birth as well. NEONATAL RESUSCITATION IN THE GRAY ZONE OF VIABILITY 8 Both the parents and physician should remember the rights of the infant as a person to be free from unwarranted pain and suffering and to be treated with dignity and compassion regardless of the chosen course of action. When the parents are educated and have had time to consider their feelings towards resuscitation in advance, they will be prepared to give or refuse informed consent. It is the right of the parents to choose what is best for their infant and for their family, and healthcare staff as well as the law need to dutifully respect that right. NEONATAL RESUSCITATION IN THE GRAY ZONE OF VIABILITY 9 References Bhatia, J. (2006). Palliative care in the fetus and newborn. Journal Of Perinatology, 26S24-6. Catlin, A. (2005). Thinking outside the box: prenatal care and the call for a prenatal advance directive. Journal Of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing, 19(2), 169-176. Donohue, P., Boss, R., Shepard, J., Graham, E., & Allen, M. (2009). Intervention at the border of viability: perspective over a decade. Archives Of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163(10), 902-906. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.161 Doroshow, R., Hodgman, J., Pomerance, J., Ross, J., Michel, V., Luckett, P., & Shaw, A. (2000). Treatment decisions for newborns at the threshold of viability: an ethical dilemma. Journal Of Perinatology, 20(6), 379-383. Hurst, I. (2005). The legal landscape at the threshold of viability for extremely premature infants: a nursing perspective, part I. Journal Of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing, 19(2), 155-168. Kuschel, C., & Kent, A. (2011). Improved neonatal survival and outcomes at borderline viability brings increasing ethical dilemmas. Journal Of Paediatrics & Child Health, 47(9), 585589. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02157.x Krug, E. (2006). Law and ethics at the border of viability. Journal Of Perinatology, 26(6), 321324. MacDonald, H. (2002). Perinatal care at the threshold of viability. Pediatrics, 110(5), 10241027. Ramsay, S., & Santella, R. (2011). The Definition of Life: A Survey of Obstetricians and Neonatologists in New York City Hospitals Regarding Extremely Premature Births. Maternal & Child Health Journal, 15(4), 446-452. doi:10.1007/s10995-010-0613-8 NEONATAL RESUSCITATION IN THE GRAY ZONE OF VIABILITY 10 Seaton, S., King, S., Manktelow, B., Draper, E., & Field, D. (2013). Babies born at the threshold of viability: changes in survival and workload over 20 years. Archives Of Disease In Childhood -- Fetal & Neonatal Edition,98(1), F15-20. doi:10.1136/fetalneonatal-2011301572 Sexson, W., Cruze, D., Escobedo, M., & Brann, A. (2011). Report of an international conference on the medical and ethical management of the neonate at the edge of viability: a review of approaches from five countries. HEC Forum, 23(1), 31-42. doi:10.1007/s10730-0119149-6 Singh, J., Fanaroff, J., Andrews, B., Caldarelli, L., Lagatta, J., Plesha-Troyke, S., & ... Meadow, W. (2007). Resuscitation in the "gray zone" of viability: determining physician preferences and predicting infant outcomes.Pediatrics, 120(3), 519-526. Stephens, B., Tucker, R., & Vohr, B. (2010). Special health care needs of infants born at the limits of viability.Pediatrics, 125(6), 1152-1158. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-1922 Sudia-Robinson, T. (2011). Neonatal Ethical Issues: Viability, Advance Directives, Family Centered Care. MCN: The American Journal Of Maternal Child Nursing, 36(3), 180-187. doi:10.1097/NMC.0b013e3182102162 Zayek, M., Trimm, R., Hamm, C., Peevy, K., Benjamin, J., & Eyal, F. (2011). The Limit of Viability: A Single Regional Unit's Experience. Archives Of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 165(2), 126-133. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.285