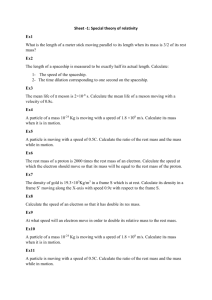

Madsen_Thesis_Draft_Final

advertisement