Intermediate-term results of recurrent cystoceles repaired with non

advertisement

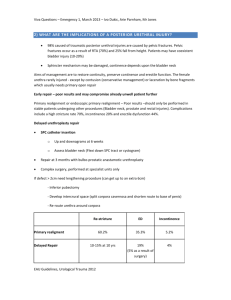

Intermediate-term results of recurrent cystoceles repaired with non-frozen cadaveric fascia By Elise S. Perer, MD and Gary E. Leach, MD Issues in Incontinence – Spring/Summer 2007 Pelvic prolapsed is a common condition affecting adult women of all ages, with an estimated 11% of all women undergoing surgical intervention by age 80 for this condition. 1 Anterior wall defects, or cystoceles, are very common in women and result from a weakness in the anterior vaginal wall support, a continuous connective tissue support from each pelvic sidewall laterally and from the anterior pubic symphysis to the sacrum posteriorly. There are two main defects responsible for cystoceles: central and lateral. Central defects are caused by a weakness in the perivesical or pubocervical fascia in the midline. Lateral defects stem from a detachment of the vesicopelvic fascia from the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis. The weakened vesicopelvic fascia allows the bladder and urethra to slide down as a unit. The etiology of cystoceles is multifactorial and includes genetic factors that determine tissue strength, parity, hormonal status, age, and previous pelvic surgery. Many cystoceles are asymptomatic; however, they can become symptomatic if the bladder descends to the level of or outside the introitus. Patients may present with a vaginal bulge or pressure while standing that may resolve when they are supine. Many women with symptomatic cystoceles also have concomitant lower urinary tract symptoms including stress incontinence, urgency with or without urge incontinence, and a sensation of incomplete bladder emptying; they may even need to manually reduce the prolapse in order to void to completion. Despite the large number of women affected by pelvic prolapse, the most appropriate technique for repair is still controversial. A myriad of surgical procedures has been developed to repair the various components of pelvic prolapse. The procedure most commonly used in the past for cystocele repair is anterior colporrhaphy, which involves plication of the pubocervical fascia in the midline, therefore reducing the cystocele. This approach corrects only the central defect and uses the patient’s inherently weak tissue. Recurrence rates with this approach have been reported as high as 50%. Correction of the cystocele defect with graft material allows for simultaneous correction of both the central and lateral cystocele defects without vaginal narrowing, and it obviates the need to use the patient’s weak native tissues. Many graft materials are currently being used to repair cystocele defects, and there are no good data to support the use of one material over others. In this article we review our results for cystocele repair with non-frozen cadaveric fascia lata in 38 patients with recurrent symptomatic cystoceles after previous failed anterior colporrhaphy with or without prior hysterectomy. Pre-op evaluation Office evaluation of patients with pelvic prolapse begins with taking a complete medical history including emphasis on urinary, bowel, and sexual function. With regard to urinary function, it is important to note any symptoms of urinary obstruction from the prolapse: frequency, urgency with or without urge incontinence, weak stream, hesitancy, recurrent urinary tract infections, sensation of incomplete bladder emptying, or the need to manually reduce the bladder in order to void to completion. It is also important to note if the patient has a history of stress incontinence and, if so, the severity of the incontinence. A complete surgical history is needed with special focus on whether a hysterectomy has been performed. If the patient still has a uterus and has a history of uterine bleeding, an abnormal Pap smear, or other uterine disease, a gynecology consultation should be obtained. The patient’s reproductive and hormonal status should be noted. It is also important to ask the patient if she is sexually active and if her sexual function is normal. Bowel function should also be assessed. Validated questionnaires focusing on quality of life can also be utilized to quantitate symptoms. A detailed physical exam is necessary. The exam should first focus on a patient’s functional and cognitive status. The neurologic exam is an essential part of the evaluation and should focus on perineal and lower extremity sensation as well as lower extremity motor function. Abdominal examination should also be performed. The vaginal vault should be examined systematically. The first focus of the exam is the external genitalia and vaginal wall, which are evaluated for abnormalities especially in the thickness and integrity of the vaginal wall. Each component of the vaginal vault should be evaluated for prolapse. Evaluation begins with examination of the anterior vaginal wall. Urethral hypermobility should be assessed. The urethra should be palpated to evaluate for tenderness or masses that may signify a urethral diverticulum. The degree of cystocele should be noted. The posterior vaginal wall should be examined for weakness. In addition, a rectal exam should be performed to help evaluate the degree of rectocele, perineal body, anal sphincter and levator tone. If the patient has a uterus, it is important to evaluate for uterine descensus by examining her while she is standing. If she has had a hysterectomy, the vaginal vault must be evaluated to assess for apical prolapse and/or enterocele. A dynamic standing MRI can also be useful to assess the degree of prolapse of all vaginal compartments (see figure 1). 2 Evaluation continues with urinalysis and a post-void residual measurement. A voiding diary and pad test can also be used to help determine fluid intake and degree of incontinence. When lower urinary tract symptoms or an abnormal urinalysis occur, cystoscopy is performed to evaluate the bladder and rule out any other causes for irritative voiding symptoms such as a bladder tumor or a stone. The urethra should also be evaluated endoscopically, and it can be further examined by palpating it over the cystoscope to rule out masses or tenderness. A renal ultrasound is generally obtained to evaluate the upper tracts for hydronephrosis due to urethral kinking in patients with significant pelvic prolapse. We strongly recommend pre-operative urodynamic evaluation before surgical repair of pelvic prolapse. Urodynamics can help to determine bladder capacity and contractility and to evaluate for bladder dysfunction. Urodynamics can also help in evaluating both stress and urge incontinence. We perform urodynamics using a 7-French dual-lumen urethral catheter as well as a rectal catheter. Bladder filling is done at 30 cc per minute. Stress incontinence is assessed both with and without manual reduction of the prolapse to reveal occult stress incontinence (figure 2). We manually reduce the prolapse, but this can also be accomplished with a vaginal pack or pessary. Prior to surgery, all patients undergo intermittent catheterization teaching in the unlikely event of temporary urinary retention. Surgical technique After receiving intravenous antibiotics, the patient is placed in the dorsal lithotomy position with all pressure points well padded. Vaginal exposure is obtained using a ring retractor with hooks, and the bladder is placed to drainage with a urethral catheter. A midline incision is made in the vaginal wall from the mid-urethra to the vaginal cuff or cervix. When there has been a prior anterior repair, the incision is made over the previous scar on the anterior vaginal wall. Emphasis is placed on maintaining dissection on the white shiny layer located on the inside of the vaginal wall. The bladder is sharply dissected off the vaginal wall. The dissection of the bladder continues laterally until the levator complex is exposed cephalad to the vaginal wall (figure 3). We routinely place transobturator midurethral slings in all patients undergoing prolapse repair. After the bladder is fully dissected off the vaginal wall, we continue dissection at the level of the mid-urethra laterally towards the obturator membrane in preparation for transobturator sling placement. Five polydioxanone sutures are then placed into the levator complex around the cystocele defect; two sutures are placed on each side of the cystocele defect; and one suture is placed in either the cervix or the vaginal cuff (figure 4). Once the sutures are placed, a transobturator mid-urethral polypropylene sling is installed. A 6-by-8 cm piece of non-frozen cadaveric fascia lata is configured to close the cystocele defect, and the pre-placed polydioxane sutures are passed through the graft material. Indigo carmine is given and cystoscopy is performed to rule out a bladder, ureteral, or urethral injury. The transobturator sling is positioned at the mid-urethra with appropriate tension (figure 5). The redundant vaginal wall is trimmed and the incision is closed. A urethral catheter and vaginal pack are placed. Both the vaginal pack and urethral catheter are removed in the morning of the first postoperative day. Most patients are discharged home later that day on oral antibiotics after a voiding trial. When there is significant uterine descensus, a vaginal hysterectomy is performed prior to the cystocele repair. During the hysterectomy, the ureterosacral ligaments are identified and tagged. Once the uterus has been removed, polypropylene sutures are placed through the ureterosacral ligaments in a high intraperitoneal location anteriolateral to the rectum. The sutures are used for a concomitant vaginal vault suspension. When there is pre-operative apical prolapse after previous hysterectomy in conjunction with the cystocele, polypropylene sutures can be placed through the ureterosacral ligaments bilaterally to be subsequently used for the vaginal vault suspension. Results A total of 38 patients with a mean age of 66 (range 31-86) years had a cystocele repair after a previous failed anterior repair done between 1998 and 2005 for Baden-Walker grade 2-4 (bladder descends to the mid-vagina or lower) recurrent cystoceles. Twentyfour patients (63%) underwent cystocele repair alone, while 14 patients (37%) had a cystocele repair plus additional prolapse surgery (vaginal hysterectomy with vault suspension, enterocele repair, and/or rectocele repair). Of the 38 patients, 76% (29/38) had had a hysterectomy prior to or concomitant with the anterior repair. The mean followup was 14 months (range 2-74); all patients were evaluated every 6 months with both physical examination as well as validated patient satisfaction questionnaires. The symptomatic cystocele recurrence rate (greater than or equal to grade 2 cystocele) was 3% (1/38). An additional 4 patients (11%) developed vault prolapse between 4 and 13 months. Of the 38 patients, 32 (84%) are greater than 50% satisfied with the surgery and 33 (87%) state that they would undergo the cystocele repair with cadaveric fascia lata again. Complications were minimal. Conclusion Despite improvements in technique and an improved understanding of pelvic anatomy, the reported success rate for anterior colporrhaphy is as low as 37%.3 Because of this, pelvic surgeons have utilized surrogate tissue to reinforce their repairs and to prevent recurrences. The use of graft material closes the hernia defect through which the bladder descends into the vagina. There is a paucity of long-term studies examining the efficacy of prolapse repair and, thus, of graft materials for cystocele repair. Our technique, as described above, uses solvent-dehydrated, nonfrozen cadaveric fascia lata to repair both central and lateral defects through a vaginal approach with minimal vaginal narrowing. We have been using cadaveric fascia lata since 1998 to repair cystocele defects and have previously reported a 7% cystocele recurrence after repair with a maximum followup of 5 years. 4 Repair with non-frozen cadaveric fascia lata is a durable procedure; it produces excellent results for repair of recurrent cystocele after previous failed anterior colporrhaphy, with high patient satisfaction and low morbidity. In a study similar to ours, Gandhi et al prospectively compared anterior colporrhaphy with and without a solventdehydrated cadaveric fascia lata patch. 5 It revealed a cystocele recurrence rate of 21% in those with the cadaveric fascia lata patch compared to 29% in those without the fascial patch, with a median followup of 13 months. Groutz et al reported on 21 patients who underwent cystocele repair with solvent-dehydrated nonfrozen cadaveric fascia lata: there were no recurrent cystoceles at a followup of 12 to 30 months. 6 Pelvic prolapse is a significant problem for many women and will continue to increase as our population ages. The evaluation of pelvic prolapse includes a detailed history of the patient’s voiding symptoms as well as a detailed physical exam and urodynamics tests. MRI can also be used to help evaluate the degree of prolapse present. Operative repair should focus on repairing all defects with one procedure. Non-frozen cadaveric fascia lata allows for correction of central, lateral, and cystocele defects without significant vaginal narrowing; long-term results are excellent. References 1. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-6. 2. Mourtzinos A, Maher M, Yu H, Raz S. Vaginal prolapse/ incontinence. Part II: Enterocele, uterine vault prolapse and posterior vaginal wall defects. AUA Update Series Volume 25. 2006: 274 3. Maher C, Baessler K. Surgical management of anterior vaginal wall prolapse: an evidencebased literature review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:195-201. Epub 2005 May 25. 4. Frederick RW, Leach GE. Cadaveric prolapse repair with sling: intermediate outcomes with 6 months to 5 years of followup. J Urol. 2005;173:1229-33. 5. Gandhi S, Goldberg RP, Kwon C, Koduri S, Beaumont JL, Abramov Y, et al. A prospective randomized trial using solvent dehydrated fascia lata for the prevention of recurrent anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1649-54. 6. Groutz A, Chaikin DC, Theusen E, Blaivas JG. Use of cadaveric solvent-dehydrated fascia lata for cystocele repair—preliminary results. Urology. 2001;58:179-83.