View an example of a textual analysis with a research

advertisement

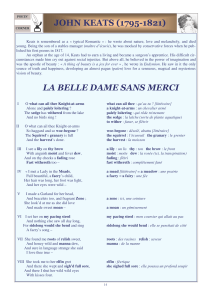

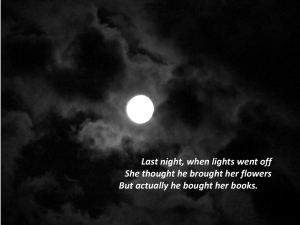

Robertson 1 Kate Robertson Prof. Victoria LeCorre English 2604 14 September 2011 Explication of “La Belle Dame Sans Merci” John Keats’s poem “La Belle Dame Sans Merci” dramatizes the conflict between dreams and reality as experienced by the knight. On a late autumn day, the speaker stumbles upon an ailing knight and asks what is wrong. The knight reveals that he had fallen in love with a beautiful lady, “a faery’s child” (14), who then abandoned him after professing her love and spending one night together. The speaker is recounting his experience with the knight to his audience. Structurally the poem is a ballad written in twelve quatrains. Keats wrote the poem with the intention of it being read as opposed to sung (Cummings). The first three lines of each quatrain are written in iambic tetrameter, while the fourth varies between iambic dimeter and anapestic/iambic dimeter. This is a variation from traditional ballad form, which alternates between iambic tetrameter and iambic trimeter. In some cases, Keats’s meter variations emphasize certain words, while in other cases it leads to awkward syntax. However, the rhyme pattern of abcb remains constant throughout the whole ballad. This creates a sense of unity. The story begins in the first stanza, when the speaker discovers the knight “alone and palely loitering,” (2) and then questions his condition in the second stanza. He describes the night as appearing “haggard and so woe-begone” (6). The imagery provided by describing the autumn also sets a sorrowful tone. Everything is eerily quiet and fading: the “sedge has Robertson 2 wither’d” (3), “no birds sing” (4), and the harvest is “done” (8). The speaker’s inquiries continue into the third stanza when he notices the knight’s pallid face; he is losing his color because of his sickness and despair. Each description of the knight is based in nature: the “lily” (9) on his brow, the “dew” (10) on his forehead, and the “fading rose” (11) on his cheeks describe his pale face and physical sickness. The knight’s personal recount of the lady begins in the fourth stanza. He meets the faery lady in a meadow. He seems instantly captivated by her beauty, stating that “her hair was long, her foot was light / and her eyes were wild” (14-15). The use of the word “wild” may suggest that the faery has a feisty, untamed nature. Throughout stanzas four through six, the knight appears to be dominant, as he states he makes all of the moves: “I made a garland for her head,” (17) and “I set her on my pacing steed” (21). Keats’s use of “steed” is quite peculiar. It could be taken literally, as in a horse that one rides, or it could be interpreted as an innuendo. The reference to the faery lady making “sweet moan” in line 20 could allude to an innuendo as well. In stanza VII, we see a shift in focus from the knight to the faery lady. Instead of the knight describing his own actions, he describes the faery lady’s actions. She provides the knight with “roots of relish sweet, and honey wild, and manna dew” (25-26). Both honey and manna are Biblical allusions, but the most peculiar of these is “manna.” In the book of Exodus, God sent manna to the Israelites as a form of nourishment. Perhaps the faery lady is a form of “nourishment” for the knight. The lady professes her love for the knight: “I love thee true” (28). After this profession, the faery lady brings the knight to her “elfin grot” (29). The knight attempts to tame her “wild wild eyes / with kisses four” (31-32). Again, the use of “wild” denotes a feisty temperament. Up to this point, Keats has built sexual tension between the two Robertson 3 apparent lovers. Therefore, the fact that the knight merely gives the faery lady “kisses four” seems somewhat disappointing; the readers might expect more than kisses at this point. In stanza IX, the faery lady “lulled” (33) the knight into a deep sleep, during which he dreamed “the latest dream I ever dream’d” (35). It is unclear whether this is the final dream he experienced, or if it is the last dream he remembers. The dream continues into stanza X. In it, the knight sees men of power such as knights, warriors, and princes that are as “death-pale” (38) as the knight himself. Alliteration on the consonant “p” in lines 37-38 emphasizes the sickliness they all experience. The men of power are subject to the same sickness and disaster as the knight. Finally, these men tell the knight that he is now a captive of the faery lady. The action returns to the knight in stanza XI when he “saw their starved lips in the gloam” (41) and “awoke” (43) from his nightmare. “Gloam” refers to the literal time of day when this occurs—twilight—but it could also represent the figurative “day” and the fading life of the knight. The knight describes the “starved lips” as “with horrid warning gaped wide” (42). This awkward syntax is a result of the shock the knight feels when he sees the faces of the warriors and princes; he is trying to search for the proper words, and fails to express them smoothly. In the final stanza, we return to the hill where we began. The knight is still alone and the day is still fading. Robertson 4 Works Cited Cummings, Michael J. La Belle Dame Sans Merci: A Study Guide. 2009. http://www.cummingsstudyguides.net/Guides6/Belle.html. 12 September 2011. “Gloam.” Def. 1. The Oxford English Dictionary. 2011. Oxford UP. September 12, 2011. Keats, John. “La Belle Dame Sans Merci.” 100 Best-Loved Poems. Ed. By Philip Smith. New York: Dover Publications. 1995. 47-48. Print. “Lily.” Def. 5Bb. The Oxford English Dictionary. 2011. Oxford UP. Web. September 12, 2011. “Lull.” Def. III, 1a. The Oxford English Dictionary. 2011. Oxford UP. Web. September 12, 2011. “Manna.” Def.1a. The Oxford English Dictionary. 2011. Oxford UP. Web. September 14, 2011. “Rose.” Def. II, 4a. The Oxford English Dictionary. 2011. Oxford UP. Web. September 12, 2011.