LEONARD Emily Ruth and HILLMAN Glenys Anne

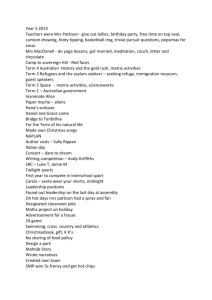

advertisement