Shockey - UIUC Intellectual Freedom is Not Social Justice – Talk

Shockey - UIUC

Intellectual Freedom is Not Social Justice – Talk Transcript

1

Many of you in the audience are familiar with the controversy surrounding the University of Illinois revoking an offer of tenured professorship in American Indian Studies to Steven Salaita last August. After Salaita's criticism of the state of Israel and the Israel Defense Forces' actions in the Gaza Strip over Twitter, Chancellor Phyllis Wise informed Salaita just weeks before the beginning of his contract that his offer would not be presented to the University of Illinois' Board of Trustees; later evidence indicated that students and major university donors threatened to withhold university support should Salaita's contract be honored. Many academic communities and organizations have spoken out in support of Salaita, decrying the University's actions as a breach of academic freedom as outlined in the American Association of University Professors'

1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure , a document of which the

University of Illinois is a signatory and which is explicitly included in tenured and tenure-track contacts tendered by the University. Though Salaita is a professor and not a librarian, his situations should give librarians as well as library school students and faculties great pause.

Academic freedom bears great resemblance to and shares many principles with American librarianship's core value of intellectual freedom, to such a point that the American Library

Association became the second official signatory on the 1940 Statement and adapted the document for librarianship in 1946. Considering the ALA's many principled defenses of intellectual freedom in official documents and ALA publications, as well as the ALA's commitment to funding organizations dedicated to promoting ALA's conception of intellectual freedom—the Freedom to

Read Foundation, for example—one would expect the ALA and its accredited library school faculties to make a demonstrative statement in defense of Salaita. This is by far not the case.

Shockey - UIUC 2

In December 2014, students of the University of Illinois's Graduate School of Library and

Information Science hosted a panel of speakers to discuss the Salaita controversy as it pertained to the information professions. During the ensuing discussion, GSLIS faculty member Dr. Emily

Knox made the following comment: "Intellectual freedom and social justice are not the same thing." Dr. Knox is correct, and thank you to Dr. Tilley, who unfortunately could not be here today, for documenting the panel for those of us following along on Twitter. This statement is just a surface comment to a larger underlying tension between upholding the rhetoric of neutrality and value-free access on one hand, and the call for libraries and librarians to be active agents working for the good of their communities on the other hand. Or, as Toni Samek put it in 2001: the tensions between Intellectual Freedom and Social Responsibility in American Librarianship. Even the

ALA's own Intellectual Freedom Manual acknowledges the tension between values. In the words of Candace D. Morgan and Judith Krug, writing on behalf of the ALA's Office of Intellectual

Freedom: "Can a library committed to intellectual freedom and to providing materials that represent all points of view also support one point of view?"

The presentation could end right here because the answer is very simple. No. But Krug and

Morgan use that question rhetorically. To understand why my answer is simple, we need to understand what ALA's intellectual freedom represents and does, as well as how it causes librarians to abdicate their social responsibilities, namely to fight for social justice within their local communities. During this talk I will focus on how the ALA's conception of intellectual freedom was formed in historical context, how the concept has gained momentum and core value status through the concept of symbolic capital using the work of Pierre Bourdieu and Emily Knox, and how this symbolic capital functions within ALA Accreditation in order to transmit the ethos of

ALA's intellectual freedom to library school students. I posit that there is a lack of social justice-

Shockey - UIUC 3 focused education and pedagogy in library school curricula, in part due to the political and activist focus of social justice education coming into direct conflict with the agency-removing neutrality rhetoric of ALA's intellectual freedom.

In the Intellectual Freedom Manual , Candace D. Morgan defines intellectual freedom as a concept that "accords to all library users the right to seek and receive information without having the subject of one's interest examined or scrutinized by others." Morgan goes on to link this definition to the First and Fourth Amendments of the US Constitution and Jeffersonian principles of democracy—namely, the fundamental importance of an educated citizenry and an unfettered marketplace of ideas free from government intervention. That sounds great, right?

ALA's intellectual freedom in practice is rarely this simple or noble. In fact, Judith Krug notes that when the ALA was founded, intellectual freedom as we know it did not exist. Intellectual freedom gained traction as a concept in librarianship through a very narrow focus: book censorship. Early librarianship was very critical of unfettered access, preferring instead to dictate the kids of texts collected in order to shepherd patrons towards a particular Enlightenment-focused intelligence and value set. ALA action against book censorship was not even a thought until

1925—but in the following decade, a series of book censorship challenges led to the ALA resolving to make defense against book censorship and intellectual freedom core values of the profession, resulting in intellectual freedom's prominence in two new fundamental documents: the

1939 Library Bill of Rights and Code of Ethics of the American Library Association. As new challenges arise and librarians take a stand to defend intellectual freedom, we learn time and again that developing such a grand principle from a narrow focus causes intellectual freedom in the library context to carry with it the legacy and implications of its historical development. As I mentioned earlier, Toni Samek's 2001 book Intellectual Freedom and Social Responsibility in

Shockey - UIUC 4

American Librarianship, 1967-1974 documented the first major internal challenge by the profession to ALA's intellectual freedom—the formation of the Social Responsibilities Round

Table. In short, despite the existence and prominence of intellectual freedom as an ethos, many librarians were engaging in collection development self-censorship to pre-emptively head off censorship challenges from their local communities, resulting in many publications' removal or wholesale exclusion from public and academic libraries' collection as a result of the Red Scare.

This issue was exacerbated, as Noriko Asato notes in a 2014 article, because the ALA maintained

(and continues to maintain to this day) a selective and extremely agnostic response to attacks on librarians, instead focusing their energy on emblematic patrons and communities affected by book censorship. Librarians were risking quality of life to be ignored by the profession. Come 1960, the broader movement of questioning our basic assumptions about American democracy, et cetera found its way into librarianship, resulting in a faction of librarians who called for the profession as a whole to reexamine our fundamental values and focus on the social responsibilities that the profession has to the community and nation. In the ALA this movement famously came to a head in the Berninghausen debates of 1978. As the Social Responsibilities Round Table was gaining traction and earning formal inclusion, former Intellectual Freedom Round Table director Keith

Berninghausen wrote a missive published in Library Journal attacking SRRT (or, "CERT") for undermining the values of librarianship and weakening the profession. That tension has not gone away, but SRRT still exists and thrives, as many members including myself can attest to. That begs the question – where is social responsibility and social justice in the ALA right now?

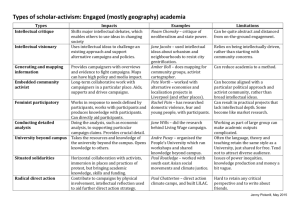

Social justice is a wide-reaching, hard to nail-down concept. For the purposes of this talk,

I will be borrowing a fantastic definition from renowned educators Sonia Nieto and Patty Bode which I found in the introduction to Lua Gregory and Shana Higgins' edited book Information

Shockey - UIUC 5

Literacy and Social Justice . The definition is framed in terms of goals and outcomes but provides a guide to overarching concepts that can guide our day-to-day praxis and work. As social justice educators, we should: "Challenge, confront, and disrupt ‘misconceptions, untruths, and stereotypes that lead to structural inequality and discrimination based on race, social class, gender, and other social and human differences.'" Note the active language—challenging, confronting, disrupting— and the focus on both discrimination and structural inequalities, which reify and reiterate discrimination. The rub between this kind of work and the value of intellectual freedom that our profession holds already; the model of social justice and social responsibility maintains that we must challenge, confront, scrutinize—actions which require professional agency and discrimination to enact; actions that are inimical to how the ALA conceives of intellectual freedom.

Where is that model in the ALA today?

I have already mentioned the Social Responsibilities Round Table—historically, SRRT has housed the progressive-thinking librarians of the ALA and has featured some of the more politically-focused and politically-charged Council resolutions that stir up controversy and ignite heated debate and occasional verbal abuse both within Council meetings and through listservs and publications—one such incident is occurring right now in the SRRT listserv concerning the same events that Dr. Salaita is currently being denied employment for. Later recognized roundtables like the GLBT Roundtable and the Ethnic & Multicultural Information Exchange Roundtable work to give voice to underrepresented groups within librarianship through political action, award sponsorships like the Stonewall, and scholarships. The last group I have included, the Spectrum doctoral cohort, is working specifically on a librarianship-focused social justice open educational resource, the Social Justice Collaboratorium, for librarians and library educators and students of all kinds to submit research, lesson plans, and activities as well as find a network of like-minded

Shockey - UIUC 6 professionals to create a community network for social justice practitioners within librarianship.

But what is notable about social justice in librarianship is what is not included.

The core curriculum of library school. Research from Julie Marie Frye in school librarianship and forthcoming research by Julie and myself about the inclusion of social justice in iSchool curricula demonstrates that it really is not part of core curriculum or teaching praxis and is offered only at a very small number of institutions like Illinois or Pratt as an elective course.

This should not be surprising in an environment where, as I have previously said, this model of education is contrary to a core value that the profession holds. But often we hail librarianship as a progressive profession despite this enormous pitfall and shortcoming. How is that possible? One answer lies in how we develop and transmit values to new professionals.

In his foundational book Outline of a Theory of Practice , Pierre Bourdieu outlines four different types of capital that an individual or an institution holds that translate into social power— economic, cultural, social, and symbolic. The latter has proven useful to understand how those with the former types of power have the authority and ability to define and legitimize values.

Recent scholarship from Emily Knox has employed Bourdieu's symbolic capital to demonstrate the importance of intellectual freedom to librarianship through two means of accruing symbolic capital: codification and institutionalization.

Codification confers symbolic capital to a concept by embedding that concept into the moral and legal codes that underlie an institution. I have already hinted at some of the ways this occurs—as a result of the pushback against book censorship in the 1920s and 1930s, intellectual freedom and anti-censorship was a looming topic in the profession during the development of two documents we now consider foundational to American librarianship—the Library Bill of Rights

Shockey - UIUC 7 and the Code of Ethics . As such, intellectual freedom and anti-censorship were explicitly written into the code.

In the Bill of Rights , "II. Libraries should provide materials and information presenting all points of view on current and historical issues; III. Libraries should challenge censorship in the fulfillment of their responsibility to provide information and enlightenment." In the Code: "II. We uphold the principles of intellectual freedom and resist all efforts to censor library resources."

Other landmark documents then quoted these documents as legitimate authority, including the

1946 Statement mentioned in the introduction, the Freedom to Read statement that informs the

Freedom to Read Foundation, and ACRL's Intellectual Freedom Principles.

Codification works in conjunction with institutionalization to solidify the authority of coded values. Institutionalization is the process of developing institutions whose foundations are coded with and made with the purpose of defending and transmitting values. To this end, the ALA has offices and roundtables that further the interests of intellectual freedom, as listed on the slide: the Intellectual Freedom Committee and Roundtable, the Office of Intellectual Freedom, and the

Committee on Professional Ethics, which reinforces the Code . Over time and with the legitimizing documents and attitudes of anti-censorship and intellectual freedom behind them, these bodies have cultivated significant influence and positioned themselves to keep doing the work with which they were tasked to do, often without questioning the basic assumptions and reasoning for their existence. The ALA itself accrues symbolic capital to justify its continued existence and hegemonic position within American librarianship as the umbrella organization under which all of these activities are undertaken. The ALA reiterates these transmitted values to new professionals through the mechanism of library school, which it controls through the economic and cultural capital of the process of accreditation.

Shockey - UIUC 8

Professional jobs without the requirement of the ALA-accredited master's degree are unicorns. The degree is a document that constitutes a large gatekeeping function to individuals who wish to enter the profession. Though librarians go through it in a myriad of forms, library school is the one experience that most professional librarians have in common prior to their current work situation. The ALA has a vested interest in being sure that librarians are trained with their interests in mind; their capital within American librarianship in all forms is so great that justifying why the ALA should be the accrediting institution for schools of librarianship to accreditation authorities is a no-brainer. Thus, the ALA has codified and institutionalized the accreditation process so as to build foundational values of librarianship into the process of library education; the

Office of and Committee on Accreditation largely control the procedures and outcomes of accreditation using the codified Standards and Process/Policies/Procedures documents.

Here, explicitly mentioned in the Standards document, schools of librarianship are specifically tasked with transmitting the essential character, philosophy, principles, and ethics of the field to students using the tools of the curriculum, student recruitment and retention, and faculty training. Student outcomes are to be derived with these things in mind as goals. Because the Office of Accreditation provides regular reviews of programs and their curricula, over time these curricula have changed to meet the Standards set forth by the office. It's important to note that the essential character, as well as the field's philosophy, principles, and ethics, are the first two tasks that student outcomes are to address. The concept of intellectual freedom enjoys a privileged, exalted place within librarianship's philosophy, principles, and ethics; thus it is often embedded in core curricular requirements for schools of librarianship in order to maintain compliance with the Standards and in order to train librarians that become renowned for their work in the field as exemplars of the field's essential character. This leaves little room for dissenting values like social justice and social

Shockey - UIUC 9 responsibility. It leaves little room for librarians to fight against the agency reduction that comes with the rhetoric of neutrality and equal, unquestioning service. It leaves little room for librarians to realize themselves as whole beings who are capable of participating politically inside and outside the workplace. It leaves little room for libraries to advocate for social responsibility in favor of continuing to give voice to a society that wants to take away basic human rights to those who are othered. It brings us back to the golden question.

"Should the library, as a social institution, serve as an advocate for social justice?" I say, unequivocally yes. I'm not sure that the ALA agrees with me. Instead it instructs us to train graduates in abdicating social responsibility and falling over the ideological sword of intellectual freedom to uphold the hegemonic status quo. That's not what I want my schooling to look like.