Summary of KwaNgcolosi Workshops

advertisement

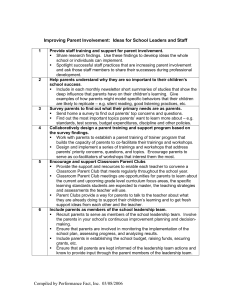

Community Selection After consultation with community leaders in the Inanda Valley of 1000 Hills (Mgeni catchment) by Umphilo waManzi’s community worker, Ma Dudu Khumalo, it was agreed that the three planned Water Research Commission (WRC) community workshops would take place in Wushwini, and include community groups from the nearby, smaller, Gudlintaba and Mahlabathini communities. These areas are all within close proximity of the Inanda Dam, in KwaZulu-Natal. Workshop 1 To get a sense of weather patterns in the area, as well as community recall of these patterns, and to enhance community understanding of how weather and the water cycle work, a timeline of ‘big weather events’ was mapped, with participants providing accompanying explanations of the impacts of each of the events. Although a 30 year history was recorded, community memory extended at least 50 years, with a weather event that occurred in 1959 being cited. Among the localized weather phenomena reported, were that apart from a drought that lasted from 1980 to 1982 (more than one rainy season), the area had rivers that flowed through it through summer and winter until 1990. The building of Inanda Dam took place from 1983 to 1987. Subsequent to 1990 the rivers have dried up, except for a few days in summer following heavy rains. Since 2000 it has been too hot and dry to grow mielies which previously were grown in the area. There has also been an increase in lightning instances where people have been killed. The community records of the changing weather patterns reflect very closely the scientific data on the area that the scientists working on this project have. Umphilo provided explanations around climate change and the water cycle, and handouts for the participants assisted the linking of the weather events and changing patterns of rainfall with climate change as it is being experienced in the valley. These concepts were unfamiliar to most of the workshop participants, although there were a few participants who had good general knowledge of both climate change and the water cycle. The activities conducted at the first workshop gave a detailed profile of the communities of this area, including their assets and vulnerabilities. An information gathering activity to map the resources of the area, including water sources and infrastructure, was conducted, and provided Umphilo with valuable insight into the facilities available to the residents of the areas. However, while it seemed comprehensive at the time, it was later apparent that there were some significant omissions, for example, community vegetable gardens and water tanks. This was interesting in light of the emphasis on water supply and access. Once the physical infrastructure had been recorded, the workshop participants gave indications of difficulties they, as community, faced, giving consideration to levels and sources of income, family structure, un/employment, illness, access to and availability of water, difficulties sustaining successful vegetable gardens, amongst others. This information was recorded in a graph, where participants rated their perceived level of vulnerability. To establish a further breakdown of sources of income, individual participants indicated by means of a pie graph the distribution of their income sources. These revealed that participants from all communities had low levels of both formal and informal/home-based employment (around 20 percent from each); 44 percent of income was from pensions; and an additional 15 percent from other social grants. Of the three areas, the majority of residents in Mahlabathini and Gudlintaba receive municipal water, with Mahlabathini also receiving grey water for garden use. Very few residents in Wushwini receive municipal water in their homes, the greatest portion of water being unpurified water supplied to standpipes from Inanda dam. Those that do receive municipal water experience disruptions to the supply of up to six months at a time. To gain further information on the community water situation, a visit from representatives from the water division at eThekwini municipality was arranged for the second workshop. Workshop 2 The timing of this workshop coincided with a funeral in the area, and the attendance was less than originally anticipated. The core focus of this workshop was the address by the municipality, which was well received and valued by community participants. It provided a forum for raising concerns about aspects of water provision and quality, and the maintenance of the supply. There was extensive discussion, and workshop participants found the opportunity to meet with municipal representatives empowering. Climate change was revisited in this workshop, and as there was little overlap between participants at the first and second workshops, much of the information shared at the first workshop was reiterated for the benefit of the newcomers. Workshop 3 The third workshop was scheduled to take place at a weekly meeting of community leaders, in order to gauge the potential or desire for developing a community action plan. It began with a focus on climate predictions indicated on detailed area maps, compiled by the consulting scientists. This was received with interest, and was the catalyst for discussion around the implications for these communities who are at the lower end of the catchment area, and stand to be impacted by water and land use higher up in the catchment area. Of particular interest to the workshop participants (mainly members of a gardening group) was a dvd on examples of community adaptations to climate change, which Umphilo screened. The emphasis was on ensuring food security, which was clearly something that the gardeners identified with. Rainwater harvesting and trench gardening were amongst the adaptations featured. An additional perspective was given on adaptation methods undertaken in Bulawayo in Zimbabwe to ensure food security, by Umphilo facilitator, Mister Danford Chibvongodze, who spoke on his personal experiences. General observations and learning This series of workshops confirmed that there is little knowledge around the concept of climate change in this area, although there is a keenness among residents for general as well as locally specific information on what climate change will mean for these communities. It is important to note that while workshop participants were unable to discuss their weather phenomena in climate change terms, they were acutely aware of weather changes that have occurred over the last thirty years, and were concerned at the impact this has had on their livelihoods. Although Umphilo was not aware of community based adaptation strategies in operation to minimize their risk, this could be attributed to insufficient time spent in the area. It is possible, also, that while there did not appear to be a community-based adaptation initiative, there may have been individual level adaptation that Umphilo was not aware of. By the end of the third workshop participants recognized the potential for initiating adaptive behaviours, and expressed a desire for exploring what sort of strategies would be appropriate in their (localized) situation. The makeup of the groups varied considerably over the course of the three workshops, with very few participants attending all three. This proved to be a shortcoming as, although the opportunity to provide information and raise awareness around climate change and water supply existed at each workshop, it was not possible to facilitate a linear progression from one workshop to the next. This may, hypothetically, have taken the route of information gathering on local conditions/information provision on climate change at the first workshop; identifying potential for adaptation strategies at the second workshop, and formalizing an action plan to mobilize these adaptations in the third workshop. The opportunity to enhance the impact of the workshops (as intervention) would be increased if workshops were conducted with an existing, cohesive group that has a sense of common purpose. Conclusion Impacts of climate change are evident in the Valley of 1000 Hills, and its residents are aware of experiencing these first hand. They were appreciative of accessing a framework of reference that facilitated their articulation of their experience of climate change, through the information sessions provided in the workshops. The congruence between the scientific reports/predictions and community accounts of the impacts of climate change in this area affirms the role of science in accurately identifying general risks for an area, although the applicability of scientific modeling to areas below a certain minimum size would need to be ascertained. This would seem to require further investigation. A community-based adaptation to these climate change impacts will require collective commitment to a plan of action. This was not accomplished in the course of Umphilo’s three workshops, due to a high changeability in workshop participants.