Oral skills lesson plan_Pron_WH question intonation

advertisement

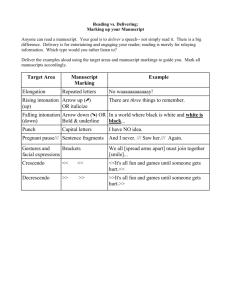

Joel Swenddal Eng 731 Fall ‘10 Dr. Whalley Pronunciation Lesson Plan: Intonation Pattern -- WH question intonation patterns Class Profile This lesson plan is designed for Intermediate students in an Intensive English Program (IEP) at a public university in the United States. The class meets 5 days per week for 3 hours per day. Of the 15 students in this class, all are between the ages of 18 and 24 and are taking the course as preparation for their official entrance into the university. The L1 backgrounds represented in the group are quite varied. The majority of these international students are from Asian countries: the largest group (nine students) are L1 Mandarin speakers from China. Three students come from Japan and one is from Korea. There is one Portuguese speaker from Brazil and one student comes from Spain. In this class, 10 of the 15 students are female. All of the students see a high level of proficiency in communication with oral and written forms of English as being instrumental to their academic goals. Much of their reason for attending this particular IEP is its relationship with the university at which it is located: all of the students have expressed interest in pursuing their undergraduate degrees at this institution once their English skills reach an advanced level. These students arrived with previous EFL instruction. Most started instruction in middle school (from the age of 12 or 13), but a few started later in high school and have only been studying for a few years. As is often the case in EFL instruction, much of their previous teaching has focused on grammar and vocabulary and has provided them with few opportunities to work on oral skills. Before arriving in this program, most had had little practice at the sending and receiving of messages in communicative tasks. As they expect oral communication in English to be necessary for success in their academic careers, they have all shown enthusiasm for lessons and activities that seek to develop their listening and speaking abilities. Linguistic Description: Intonation patterns for WH-questions In the definition used by Celce-Murcia et al. (2010, p. 231) intonation is “the rising or falling of the voice to various pitch levels during the articulation of [an] utterance.” Together with prominence (also called “nuclear stress”) placed on certain words in a linguistic unit, intonation in English is used to signal various pragmatic meanings. For example, intonation and prominence interact to highlight important information, convey affect, and to signal different interpretations of a grammatical structure (Celce-Murcia et. al, 2010). In English, each “intonation unit” also has its own “intonation contour” (pitch arrangement) and depending on contextual and speaker factors, an utterance can be broken into multiple units (or held together as one). According to Celce-Murcia et al. (2010) an intonation unit: 1 1. is set off by pauses before and after; 2. contains one prominent element (marked by longer syllable length and louder volume as well as pitch change); 3. has an intonation contour of its own; 4. usually has a grammatically coherent internal structure (251) Depending on various contextual and speaker factors, an utterance can be broken into multiple units or, as often happens in rapid speech, be united with a single contour. Discourse context is an incredibly important factor in the English intonation system because prominence may shift with new or highlighted information in an utterance (related to the communicative intentions of a speaker) As prominence is distributed in the intonation unit, intonation contour shifts along with it, since it centers on the prominent element (Celce-Murcia et al., 2010, p. 235). Although it is meaning-dependent, intonation in English displays observable patterns that unite certain grammatical structures with common pragmatic meanings. Because intonation guides the interpretation of an utterance (together with other features of the context) and since intonational meanings are far from universal across languages (Levis, 1999), it is important for learners to be able to identify and practice producing the most usual patterns of English. The most common pattern for WH- information questions in English is similar to the unmarked pattern in declarative statements. Using the scale employed by Celce-Murcia et al. (2010), with 1 being lowest and 4 being highest pitch, the “certainty” pattern of these structures can be written as 2-3*-1 (* marks the prominent element in the unit). See Figure 1.1 below. Common WH-pattern: certainty Alternate WH-pattern: uncertainty 3 3 2 Where are you going? 2 Where are you going? 1 1 Figure 1.1 Figure 1.2 Celce-Murcia notes that this falling pattern, used to mark informational questions, is often problematic for learners, who may think that all questions should be marked with rising intonation (the “uncertainty” pattern). Also, the initial WH- word does not typically receive the prominence assignment (usually this word, often corresponding to the most important or new information, is found near the end of the sentence). However, when a hearer has had difficulty making out a part of a speaker’s utterance, a different intonation pattern can often be observed. Using identical wording and syntax, a speaker will often use a 1*- 3 pattern, this time placing prominence (marked by low pitch) on the initial question word. This rising intonation more closely resembles the typical 2-1*-3 “uncertainty” pattern seen in yes/no questions. The pragmatic signal here requests a repetition of the utterance, 2 usually because it wasn’t fully understood. It can also signal surprise or disbelief. See Figure 1.2 above. Finally, an additional signal of surprise or disbelief is seen in the use of an uninverted WHquestion (“He bought WHAT?” instead of “What did he BUY?”). Here, the intonation pattern is the 2-1*-3 pattern, but since the prominent word is no longer at the beginning, it sounds different than the 1*- 3 arrangement. With all of these patterns, it is important to keep the question of prominence assignment in mind. Depending on the informational interest of the speaker, the focus element may shift (Celce-Murcia et al., 2010) Objectives 80% of the Ss, 80% of the time will be able to: 1. distinguish the three WH-question intonation patterns 2. comprehend the pragmatic meanings of the different patterns 3. decide which intonation/structural unit should be used in different discourse contexts 4. accurately and appropriately produce the patterns as they correspond with different communicative intentions 5. correctly interpret and respond to utterances that use these patterns Related material During oral communicative practice activities in earlier lessons with this class, the instructor made careful note of pronunciation difficulties that were impeding clear communication. Along with some difficulties on the segmental level (several Ss needed help with the /r/ - /l/ distinction), the teacher noticed some common problems on the suprasegmental level. Some students appeared to use the same rising intonation for all questions while several others seemed to have a rather flat rendering of the pitch: it didn’t often rise or fall to a level that would send a noticeable pragmatic message. Several of the students appeared to be stressing almost all content words with equal levels of prominence. So, in addition to some early pronunciation lessons dealing with connected speech, reduced forms and segmental phonetic features, the instructor built in several lessons that dealt with word stress, sentence stress, prominence and major intonation patterns. In two previous lessons, the Ss identified and practiced using the two major intonation patterns for declarative statements and yes/no questions, as these provide a noticeable contrast between falling and rising intonation. Almost all of the students were able to successfully produce the patterns for these two purposes during controlled practice, but in the fluency activities, many mistakes cropped up, indicating that, as expected, conscious monitoring of intonation becomes difficult when language learners focus on meaning. This lesson with WH- question patterns is a natural follow-up to the prominence lesson and the yes/no vs. declarative intonation lesson. The pitch change in the intonation group hinges on the prominent element and the patterns used for the WH- questions can be rising or falling, depending on the purpose. This lesson builds on the student’s familiarity with those features and applies them to new pragmatic purposes. 3 Rationale A. Why this feature? While targeting student pronunciation difficulties on the segmental level helps prevent misunderstandings of individual lexical units, it has been observed that, because of awareness of discourse context and negotiation strategies, interlocutors are often able to arrive at correct understandings of messages even when some words are mispronounced (see Celce-Murcia et al (2010, p.221) for an example of this). On the other hand, the organizational features of language on the suprasegmental level -- rhythm, sentence stress, prominence, and intonation -- when used incorrectly can create frustration, significant misunderstandings, and sometimes, especially in the case of incorrect intonation, lead to perceptions of rudeness and confusion about the speaker’s intentions (Celce-Murcia et al, 2010; Gumperz, 1982). Of course, in a heterogeneous English language class, not all learners experience the same difficulty with the same suprasegmental features. Depending on learners’ goals, they may not need to achieve native-like control of all of them. In fact, in the area of intonation, Levis (1999) notes that, even among groups of native speakers, perceptions of intent as expressed through intonation may vary. Nevertheless, it is possible to generalize about certain commonly-occurring patterns in English; these patterns, if not shared by a student’s L1, may not be acquired without a great deal of attention and practice. Celce-Murcia (2010, p. 249) notes, for instance, that many “learners frequently associate questions with rising intonation, and as a result may have difficulty correctly producing and/or interpretting many wh- questions” since in their unmarked form they typically receive a falling intonation. The selection of different wh- intonation patterns for this lesson on suprasegmentals is a response to the different intonation difficulties that students in the class seem to be experiencing. More than half of this group speaks Mandarin Chinese as a native language and contrastive analysis of the differences between English and Chinese intonation reveals dramatically different uses for pitch. Since pitch changes in Chinese distinguish lexical items whose pronunciation is otherwise identical, acquiring the use of intonation that affects interpretation of a whole group of words can pose a significant challenge (Swan, 2001). Swan (2001) notes that lack of skill with the use of these patterns can cause the speech of Chinese speakers to sound “flat, jerky or ‘sing-song’ to English ears” (p.313). The “flatness” of many of these students’ speech was noticeable and distracting and often left the listener wondering if a statement or a question had been intended. Also, many of the content words of the utterance appeared to receive an identical stress, which often made the point of the sentence unclear. The second largest group of learners in this class is Japanese. With these students it seemed that almost all of their questions, both wh- and yes/no questions alike, tended to rise in pitch at the end. With many yes/no questions, this sounded fine, but when wh- questions rise in pitch, it signals uncertainty about the message. In this case, though the teacher usually had little difficulty in guessing the intended meaning, it seemed important to make learners aware of the pragmatic message they were sending with their intonation. Even though the Portugese, Spanish, and Korean students did not appear to be having the same troubles as their classmates, the Spanish student’s pitch changes overall seemed very limited. Swan (2001) confirms that pitch range is typically narrower in Spanish and that emphasis is assigned through extra syllable length rather than extra pitch assignment. 4 B. Why these activities? This seventy minute pronunciation lesson forms one part of a two hour oral skills class which these students take part in two days per week. Activities in three previous oral skills classes have given students practice at identifying and producing correct sentence stress, prominence of individual words related to speaker focus, and the intonation patterns seen in many declarative sentences (rising) and yes/no questions (falling). In general, students are able to identify the most prominent words in an intonation group (identified by length, volume and pitch characteristics). Although many of them still have difficulty using prominence appropriately in their own speech, they are aware of the feature and its use in guiding a listener’s interpretations of what is most important or new in an utterance (Celce-Murcia, 2010). The activities of this lesson require this basic familiarity with these features and will give students additional practice with them alongside their practice with the new pattern. The stages of the lesson follow those recommended by Celce-Murcia et al. (2010, p. 45). After establishing a communicative context (here related to shopping) and reviewing the prominence and yes/no patterns from earlier lessons, the teacher engages students in identifying and analyzing the new wh-question patterns, linking them with their typical meanings and uses in discourse. A listening discrimination stage, in which learners focus only on correctly identifying the different intonation patterns in highly controlled input, is followed by several stages of production in which learners use the feature in exercises that are successively less and less controlled. The most controlled practice gives them an opportunity to accurately produce the features multiple times while the final communicative task has a focus on fluency and requires the learners to use the new features in meaning-focused interactions. This activity framework follows suggestions by Schmidt (1990) involving the need for the initial “noticing” of a feature in order to facilitate acquisition. “Noticing” describes conscious attention to some aspect of the language code. After learners have analyzed the feature and can identify it, information processing theory predicts that learners will pass through a period in which the short term memory demands of trying to accurately produce the new feature will be great. Successful acquisition will at first require a great deal of conscious monitoring of the performance (CelceMurcia et al., 2010). In other words, full, fluent integration of the feature into speech won’t occur until the learners have had many opportunities to practice recognizing and producing the feature accurately. In this lesson, controlled and guided practice activities (here a dialogue repetition task and a guessing game) precede the communicative activity. The communicative task, coming at the end of the lesson, aims to create a situation in which learners can put the new feature to use in purposeful exchanges of information. “Automatized” use of the feature is thought to arise out of this type of fluency and meaning-focused interaction (Celce-Murcia et al., 2010). The fluency task in this lesson (a dialogue-creation exercise) will provide opportunities for real negotiation of meaning and pushed output. Also, since the “automatization” process requires many efforts at production over an extended period of time, it is recommended that teachers review often and create ongoing opportunities to practice previously studied features (Celce-Murcia et al. 2010, p.45) To achieve this, the teacher in this lesson revisits previous lesson topics at several points. 5 The Lesson (70 minutes) A. Materials 1. Dialogue transcripts for each Ss pair -- cut-up (Appendix A) 2. Audio file of dialogue performance 3. Listening Discrimination Worksheet for Wh- questions (Appendix B - Celce-Murcia, p. 261) 4. Audio file to accompany Listening Discrimination exercise 5. Partner A and B slips with dialogue lines -- for Controlled Practice task (Appendix C) 6. Cut-out slips with pictures -- for Guided Practice task (Appendix D) Lesson Stages 1. Introductory context setting and inductive presentation: (20 minutes) T reminds Ss of two kinds of intonation pattern reviewed in the previous lesson. After establishing the context of shopping, he then changes their focus to a different kind of question through the use of the dialogue. Ss assemble the dialogue and then induce rules for Whquestion intonation based on their observation of the different patterns heard in the listening text. T: Good morning everyone! Happy Monday! Do you remember what I said we’re going to talk about today? S: No. I forget. T: Well, what did we work on last Wednesday? Does anyone remember? Ss: Intonation. T: Right. Does anyone remember the 2 patterns that we talked about? Robin? S: We talked about rising and falling. (The Ss moves her hand up and down to go with the words because this was part of the way the class responded to the two different patterns in the lesson). T: Yes. Good. And when do you hear falling intonation? S: In a statement. T: Yes. And how about the rising? S: In a question. T: Actually, that’s not quite right. What KIND of questions did we use it in? S: It was Yes No question. T: That’s right. So can someone give me an example. Tuan? S: (thinks for a moment) Do you like birthday cake? T: Yes. I love birthday cake. And yes, your intonation was rising. That is the pattern we worked on. Good. (on the WB, T writes the sentence “Tuan likes birthday cake.” two times, side by side, numbering them 1 and 2) Transition: Here the T will review the points in the prominence lesson. T: So, OK. Remember that there is more than one way to say this sentence. Different kinds of intonation. Does anyone remember this? S 1: Yes. “Tuan likes BIRTHday cake.” (with falling intonation) T: That’s one way. Good. That’s the most common way. But what if you wanted to focus on 6 Tuan? You mean that Tuan likes it and not someone else. How would you say it, Maria? S2: Um. You say “TUAN likes birthday cake.” T: Good. Everybody repeat the regular way (pointing to the first sentence). Ss: (in chorus) “Tuan likes BIRTHday cake.” T: And then, how do I say this if someone says: “Who likes birthday cake?” Ss: (in chorus) “TUAN likes birthday cake.” T: Yes. Does everybody remember this? (many Ss nod) OK, so quickly turn to the person next to you and say the sentence in three different ways. (Ss do it.) Transition point: At this point the teacher uses a Q/A activity to set the context and draw attention to the pronunciation feature. He goes on to ask them inductive questions to get them to notice the most common WH pattern (certainty). T: OK, then. I want tell you all about something that I did over the weekend. I bought something that I really wanted. But... I don’t want to tell you the whole story at first. First, you should try to guess what I bought. You will need to ask me questions to find out, but there is only one question you CAN’T ask. Does anyone know? Ss: (they’ve done this before) “What did you buy?” T: (laughing) Yes. That is the question. You can’t ask it. You can only ask questions to get clues. Raise you hand when you think you can guess it. S1: Just the yes/no question? T: No. You can ask any kind of questions. Everyone in class gets to ask one question and then you can guess what I bought. So, think of your question. S1: Any question? T: A question about what I bought. Can you give the class an example? S1: Is it big? T: No. It’s not very big. I can hold it in my hands. Ok. Do you see? (Everyone nods.) So now think of a question. (Ss think for a moment.) T: Ok. Let’s start. You go first, Nika. S: Um... Where did you buy it? T: I bought it at a store called Best Buy. (T goes on to collect a number of questions. When WH-questions are asked, he writes them on the WB.) (After everyone has asked a question, the Ss guess that the T has bought a new iPad.) T: Good guess, everybody. Now, look at the sentences on the board. What kind of questions are these? S: Information questions. T: Yes. I’m going to read some. When I read them, think of two things. Which is the main focus word and does the intonation rise or fall? (T reads a sentence several times and Ss listen.) T: So, which was the main focus word? Ss: The last word. T: Right. And did my voice rise or fall at the end (moves his hands with the words) 7 Ss: Fall. T: Yes. So does this question sound like the Y/N questions? Ss: No, it’s falling. T: And where did it fall? Ss: On the focus word. T: That’s right. But, I don’t want you to think that all information questions have falling intonation. It is very common, but not always. Transition Point: Now the teacher will use a dialogue (related to the context) to help students identify the other WH-question intonation patterns (showing surprise and request for repetition). First the Ss put it in order to establish meaning and then they listen to distinguish the intonation. (T takes out some slips of paper.) T: So when I came home after buying my iPad this weekend, I had a conversation with my wife Heather. Ss: Ohhh... Is she angry? T: Well, I’ll let you find out. Here is our conversation. It’s all cut up. You and your partners will work together to put our conversation in order. So let’s make groups of 4. (Walks around and assigns Ss to groups; they move their desks together). (See Appendix A for transcript) T: So, work together and put this conversation in order on your desk. Then, when you finish, take turns reading it to each other. So, Eun Ha, what are you and your partners going to do? S1: We read the conversation and organize. T: Right. Put the parts of the conversation in order. OK, here are the conversations (T hands out the dialogues and Ss go to work. When they finish, they take turns reading them. The T monitors and most of the Ss are using a mix of upward and downward intonation on the questions. They aren’t really focusing on it because the T hasn’t drawn their attention to it yet, but they have arrived at a correct ordering of the conversation and have put the WH question that requests a repetition and the one that shows surprise in the right place). T: OK. Good. So was she happy with me? Ss: No, she was angry. T: Yes, she was. But I guess I deserved it. I should have asked her I think. S: (laughing) Yes, you’re bad. T: I agree. It was a mistake. Alright. So everyone look at the script. How many Wh- questions are there? S: Eight questions. T: Yes. Eight. Now you’re going to listen to our conversation. It’s not our real conversation. We recorded it again later for you to listen to. After she wasn’t angry with me anymore. S: So now she’s happy with you? T: Well, now she likes the iPad, so she’s not angry. When you’re listening, pay attention to the intonation in the questions. (he moves his hand up and down) Decide what the focus word is and does the sound rise or fall on the focus word. On your paper, underline the focus word and then make an up or down arrow for the intonation. Like this. (T marks one of the board sentences: 8 “What were you thinking.”) Any questions? Ss: Ok. No questions. T: I’m going to play it 2 times. Ss: OK. That’s good. (T plays the recording. Some Ss mark all the sentences on the first try, but the T tells them to check their work as he plays it again. By the end, everyone has marked them.) Transition: Consolidating the point/inducting rules T: OK. So do all the wh- questions fall? Ss: No. Some go up. T: Which ones go up? Ss: (Quoting) “What did you say?” “What is it?” T: All together. “What did you say?” “What is it?” Ss: “What did you say?” “What is it?” (drills this a few times until everyone has done it) T: Are there any more like this? Ss: Line 9. “You bought a WHAT?” T: Good. And in those sentences, what was the focus word? The word that was loudest and longest and where the sound started to rise? Ss: On the question word? T: Good listening. It IS on the question word in those sentences. So, look at those sentences, read them and try to figure out the reason. Why does she use different intonation there and why does she focus on a different word? I’ll give you a minute. Tell your partners what you think the reason is. (Ss discuss as they look at the dialogue.) T: OK. Any ideas? Nika? S: Um. I think. She doesn’t hear him, so she ask him again. And surprised about it. I think she says like too much money and she is angry. T: Which one shows her surprise? David? S: Um, I think where she says: “Oh my God. You bought a WHAT?” She’s surprised about this. T: Yes. Does she know what he bought? S: Yeah, she knows. But she can’t believe. T: And what is different in the word order? Eun Ha? S: WHAT? At the end. Not in the beginning. T: Yes. That’s common when people are surprised. So can you think of the pattern for the intonation in WH- questions. Tell you partners what you think. (Ss talk and then T elicits the rules and writes them on the WB: 1) Use falling intonation on the focus word when it is a request for information. 2) Use rising intonation on the focus word when you are showing surprise or you want someone to repeat.) (At this point, the T conducts a quick choral drill with the sentences, pointing at the different whquestions in the dialogue and having the whole class say them together.) 9 2. Listening discrimination practice: (10 minutes) Using a listening discrimination activity from Celce-Murcia (2009, p. 261) (Appendix B). Here, the students listen to identify the intonation of a question and then choose one of two responses. Only one correctly fits the intonational meaning of the question. T: Now that you see these patterns it will be easier to understand the meaning of someone’s intonation. Let’s practice hearing the intonation and then choosing a correct response. On the WB, T writes the following: A: I’m going to California next week. B: Where? A: __ San Francisco __ California T: OK. Person A is talking to Person B. Person A says “I’m going to California next week.” If person B says “Where?” (modeling the falling end pitch), what would be the better answer to the question? Ss: San Francisco. T: And what if B says “Where?” (modeling the rising end pitch). What is the better choice? Ss: The other one. California. T: Why is that the right one? Anyone? S1: He wants him to repeat. But the first one is a normal question. Like where in California. T: Right. He heard it and now he’s asking what part of California. An information question. So, I’ll say “Where” and if my intonation rises, what do you say? Ss: California T: And if it falls…? Ss: San Francisco. (They practice a few times until the T is sure they can hear it.) T: We’re going to listen to some short dialogues. This worksheet is just like that example. If you hear the rising intonation, choose the best answer for that meaning. If it’s falling, choose the best answer for that meaning. OK? Ss: OK. (T hands out the worksheet and then plays the dialogues. After the first listen, the T has the Ss listen again to check their answers.) T: So, it looks like most everybody is hearing the different intonations, so let’s practice saying it now. 3. Controlled practice exercises (production): (5 minutes) Ss interact using two short dialogues related to telling somebody about a big purchase (Appendix C). They decide the intonation that is appropriate for the questions and practice with a partner, but since they can only read their own lines, there is a bit of an information gap. Here the T monitors closely and helps anyone that appears to be having difficulty. 10 T: (handing out the paper slips) If you have an A on your paper, stand up and find a person with a B. Then sit down together. You’re going to practice these dialogues. (Everyone moves around to find a new partner.) T: Everybody look at side 1. Partner A will begin. You are going to read your line, but think about the intonation you will use. You have to listen to what your partner says because that might mean that you need to change intonation. Are there any questions? Tom? Eun Ha? S: I just say the lines? T: Yes, you say the lines, but think about your voice. Focus on your intonation. If you think your partner says it wrong, wait till the end and then tell them. OK? Help your partner if you think they do it wrong. What are you going to do Tom? S: I just say it with the intonation. Rising for repeat or surprise. Falling for normal information. T: OK. Go ahead. (T monitors and the class works on the dialogues for a few minutes. At several points, the teacher helps students who are having difficulty assigning prominence to the focused word.) Example: S: It’s a what? (starting the lowest pitch at the beginning). T: No. Listen. “It’s a WHAT?” S: Oh, yeah. “It’s a WHAT?” 4. Guided practice exercises: (15 minutes) The Ss play a guessing game with pictures (Appendix D). The pictures show a number of different clothing accessories or tools needed for different activities. All are small items with interesting uses and purposes. An alternate version of the activity would be to have the students think of the items themselves. T: So now let’s practice with a guessing game. Remember at the beginning you asked me questions and tried to guess what I bought? Ss: Yes. T: OK. Well now you’re going to do the same thing with your partner. Work with the same person. I’ll give each person three pictures. Don’t show your partner. Your partner needs to guess by asking a lot of questions. But there is one question you can’t ask. Right? Ss: Yes, “what is it?” (several say it rising) T: Wait. Which intonation is right if you don’t know and I haven’t said it? S: Falling intonation. “What is it?” (doing it correctly) T: Perfect. So you can’t ask that question, but, you can ask for clues. Are there any questions about the activity? S: What are the items? T: They’re on these pictures. You get three pictures each. And DO NOT show them to your partner. Here you go. (Hands each Ss three pictures). T: So, remember your intonation. If you don’t understand or you want your partner to repeat what intonation would you use? S: Rising. 11 T: Right. And to make it more polite, what could you add? Ss: (Look confused). T: If you don’t understand what they said, is it very polite to just say “What?” S: Maybe? T: With your friends, yes it’s OK, but with your boss, what could you add... to show why you’re asking? S: I don’t know. T: With my boss, I might say “Sorry, could you repeat that?” or “I’m sorry, what did you say?” (T writes these on the board.) What is my intonation with those? S: Rising. T: Yes. Rising. The rising shows we’re uncertain. OK? Are you ready to try it? Ss: Yes... (The activity begins and the T monitors. Several students don’t know the English names for some of the items, but since they still ask a lot of questions, they still get practice with the target features.) 5. Communicative practice (20 minutes) Here, the Ss make and perform a dialogue with the different intonation patterns of WHquestions and at least 1 yes/no question Transition: T confirms that they have understood the point about politeness and intonation. T: Good work, everyone. I think that everyone is really getting this. Remember, which of these is more polite in asking for repetition. “What?” (rising quickly and sharply) or “Sorry, what did you say?” (using a softer, slower rise)? Ss: The first one. T: Really? Which would you use with your professor? S1: The first one... “What?” Ss: (laughing) T: Well, probably not. It can sound rude if you’re not friends. But with your friends, it’s probably OK. S1: I know teacher... Just joking. T: I know... OK, so now you’re going to make your own dialogue. Just like my dialogue with Heather. (Ss are still in pairs). So, there are some requirements. You need a WH question for information, one for repetition, and one for surprise. And, you need at least one yes or no question. (Numbers these 1- 4 on the WB). S: Who is talking? T: You choose. You decide WHO you are and decide WHERE you are and WHAT you’re talking about. And don’t tell us. When you perform it, we will try to guess the situation. S: Do we need to write it? T: Yes, one person should be the writer. Any questions? Tuan? S: Should I be myself? T: You can be yourself OR you can be another character. Someone else. Any more questions? T: So you have 7 minutes to write the dialogue, then 5 minutes to practice and then we’ll 12 perform them. S: OK. T: Let’s go! (The T circulates during the activity, monitoring the progress. Several groups are having trouble thinking of a context, so the T gives them an idea: One friend telling the others about a big party from the night before. After each group performs, the T asks the audience members to recall a question with the rising intonation and one with the falling intonation. The students also guess what the situation was and who the characters were.) Transition: Wrap up T: Amazing dialogues everyone! Good job! Very creative. Now it’s time for break. We won’t focus on intonation for two weeks, but write these rules down in your notebooks if you didn’t already. Some of you already did. Also write an example for each one. So what’s the homework, Ji-Yeong? S: Just write the rules and examples in your notebook. T: Yes. Draw a line for the intonation, just like on Wednesday. (Models this on a question written on the board.) Any questions? Ss: No! T: OK. Have a nice break and come back in 10 minutes! 6. Feedback and correction a) Description and analysis stage: Monitoring at this stage will focus on whether or not Ss are able to identify the different patterns and notice the prominent lines in the dialogue. During the listening, the T will circulate and watch as the Ss work together to mark the script. He’ll play it three times (it’s not very long) to allow them to check their answers. b) Listening comprehension stage: After playing the mini-dialogues twice, the teacher will do open class feedback (elicit the answers from different Ss) to allow everyone to compare their answers. c) Controlled practice: In this activity, the T circulates and monitors each pair’s performance. He has instructed Ss to correct their partner’s intonation if they think it’s wrong, but he will also listen to the short dialogues and give feedback if he hears a mistake. If several Ss are having trouble, at the end of the activity he will divide the whole class into two and do a choral drill of the dialogue (one side of the class is speaker A and the other is speaker B). d) Guided practice: In the Q/A guessing game activity, the T will monitor closely and collect examples of sentences that show incorrect intonation. At the end, he will write one or two of them on the WB and drill the whole class in different ways to render the same utterance with different intonations. e) Communicative practice: As before, the T circulates and helps Ss both with context planning (some Ss groups may have trouble thinking of a dialogue context) and any intonation problems. 13 7. Contingency plan In the unlikely event that another activity is necessary (this lesson is already jam-packed), the teacher could dictate a short dialogue containing different varieties of questions and statements (since the Ss have had two lessons on intonation at this point). After writing down the lines, the Ss could mark the intonation using lines drawn over the words. Then, they could guess the characters and the situation. A dialogue could look like the following: A: I can’t believe she did that to me. B: What? What did she do? A: Didn’t you hear? B: No. I didn’t hear anything? A: She didn’t tell you? B: No. Nothing. A: S he ended it. After 2 years... I’m can’t believe it. B: Really? That’s terrible. But don’t worry, you’ll feel better soon... REFERENCES Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D., & Goodwin, J. M. (2010). Teaching pronunciation: A course book and reference guide. New York: Cambridge University Press. Gumperz, J. (1982). Discourse strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Levis, J. M. (January 01, 1999). Intonation in Theory and Practice, Revisited. Tesol Quarterly, 33, 1, 37. Schmidt, R. (1990). The Role of Consciousness in Second Language Learning. Applied Linguistics, 11, 129-158. Swan, M., & Smith, B. (2006). Learner English: A teacher's guide to interference and other problems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 14