Antibiotic Awareness Week - Fact Sheet

advertisement

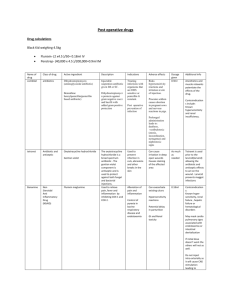

Action 3: Document indication and review date Documenting the indication for therapy is an important Key points than necessary increases the risk of selection of antibiotic resistant organisms. Document the indication, intended duration and review date for therapy to ensure timely review aspect of prescribing any medicine. It enhances the and optimisation of antibiotic use communication between team members and ensures a shared understanding of the patient’s clinical condition Continuing courses of antibiotics for longer Utilise the expertise of pharmacists where and rationale for therapy. possible to ensure optimal treatment regimen Despite the importance of documenting indication as and duration part of safe antibiotic prescribing, results from the 2013 National Antimicrobial Prescribing Survey (NAPS) i show that out of 12,800 individual prescriptions reviewed, 30% did not have the indication for therapy documented Engage senior clinicians to lead and support a prescribing culture that includes documentation of indication, intended duration and review date in the hospital medical record. Documenting indication for therapy can aid in optimising the dosing regimen of antibiotic therapy.1, 2 Pharmacists can play an important role in optimising dosing for the clinical condition by checking dosing regimen against guidelines such as Therapeutic Guidelines: Antibiotic3 to ensure the prescribed dose is appropriate to the patient’s individual characteristics (e.g. renal function, weight) and clinical condition. Ensuring the correct duration of antibiotic therapy is important to help minimise the risk of antibiotic resistance. Courses of antibiotics are often continued for longer than necessary. This may occur because prescriptions are not time limited. Contrary to popular belief, selection of antibiotic resistant organisms increases with longer courses of antibiotics,4,5 as does the risk of other unwanted effects including increased length of hospital stay. For antibiotic prescribing, studies have shown that documenting indication and review date of therapy on hospital medication charts decreases unnecessary antibiotic use and reduces the incidence of Clostridium difficile (C.difficile).6 Documenting the indication, intended duration and review date at the commencement of therapy can also help ensure timely review of the patient’s progress, response to therapy and the decision to de-escalateii or change therapy, cease or switch from intravenous to oral therapy. Fact Sheet Action 4: Review and reassess antibiotics at 48 hours provides further information regarding the importance of regularly reviewing antibiotic therapy. i Further information about the NAPS including results of the 2013 survey is available at www.naps.vicniss.org.au ii De-escalation – refers to converting to targeted therapy once the pathogen and its susceptibilities are known Useful resources Refer to Therapeutic Guidelines: Antibiotic,3 for guidance on the duration of prophylactic, empirical and targeted antibiotic therapy. The Antimicrobial Stewardship (AMS) Clinical Care Standard. The Antimicrobial Stewardship (AMS) Clinical Care Standard aims to ensure that a patient with a bacterial infection receives optimal treatment with antibiotics. It provides advice to clinicians, consumers and health services on key components of care related to antibiotic therapy. The AMS Clinical Care Standard is due for publication late 2014. For more information, visit www.safetyandquality.gov.au/ccs References and further reading 1. Duguid M, Cruickshank M (editors). Antimicrobial Stewardship in Australian Hospitals. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2011. 2. Dellit T, Owens R, McGowan J, Gerding D, Weinstein R, Burke J, Huskins W, Paterson D, Fishman N, Carpenter C, Brennan P, Billeter M, Hooten T. Infectious Diseases Society of America (ISDA) and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2007;44(2):159-177. 3. Antibiotic Expert Group. Therapeutic Guidelines: Antibiotic. Version 14. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd; 2010. Note: The next edition of Therapeutic Guidelines: Antibiotic (version 15) will be published in November 2014. 4. Richard P, Delangle M, Merrien D, Renaud A, Minozzi C, Richet H. Fluoroquinolone use and fluoroquinolone resistance: is there an association? Clinical Infectious Diseases 1994:19(1):54-59. 5. Guillemot D, Carbon C, Balkau B, Geslin P, Lecoeur H, Vauzelle-Dervroedan F, Bouvenot G, Eschwege E. Low dosage and long duration of beta-lactam: risk factors for carriage of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Journal of the American Medical Association 1998:279(5);365-370. 6. Botros S, Nathwani D. 2012. How to decrease the risk of Clostridium difficile in a ward environment and help prevent the emergence of any new cases – a Ninewells success story. Poster presented at the International Society for Quality in Health care 29th International Conference, Geneva 21-24 October 2012. Date of publication: 24 October 2014 This document is intended for use by health professionals. It has been created from information contained in Antimicrobial Stewardship in Australian Hospitals 2011 and reviewed by clinical experts. Reasonable care has been taken to ensure this information is accurate at the date of creation. This fact sheet is intended to be used in its original version and can be downloaded from the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care web page www.safetyandquality.gov.au “No action today, no cure tomorrow” is adopted from the WHO World Health Day 2011. 2