some sociological concepts and methods for psychiatrists

advertisement

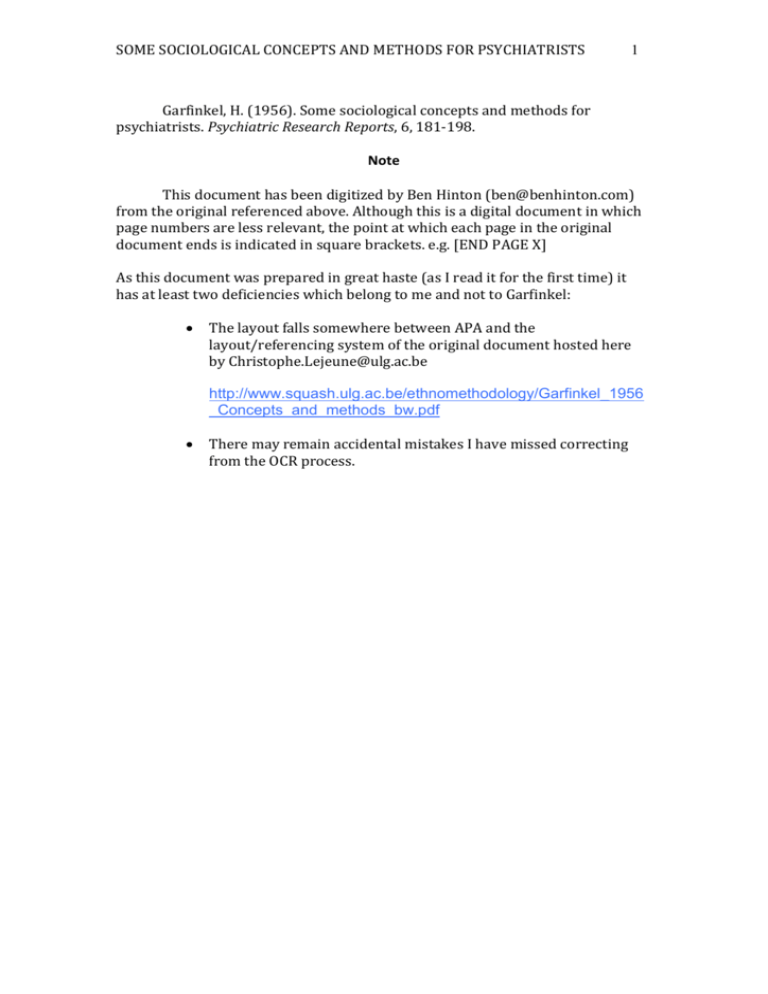

SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 1 Garfinkel, H. (1956). Some sociological concepts and methods for psychiatrists. Psychiatric Research Reports, 6, 181-198. Note This document has been digitized by Ben Hinton (ben@benhinton.com) from the original referenced above. Although this is a digital document in which page numbers are less relevant, the point at which each page in the original document ends is indicated in square brackets. e.g. [END PAGE X] As this document was prepared in great haste (as I read it for the first time) it has at least two deficiencies which belong to me and not to Garfinkel: The layout falls somewhere between APA and the layout/referencing system of the original document hosted here by Christophe.Lejeune@ulg.ac.be http://www.squash.ulg.ac.be/ethnomethodology/Garfinkel_1956 _Concepts_and_methods_bw.pdf There may remain accidental mistakes I have missed correcting from the OCR process. SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 2 Some Sociological Concepts and Methods for Psychiatrists Harold Garfinkel PhD* I. The Subject Matter of Sociology (a) Social Organization Sociologists typically talk about "an organization" as if they meant what the average person does when he refers to General Motors as "an organization," i.e. a concrete, specific structure found in the world along with "chairs" and "tables." But if you interpret the sociologist's favorite term as common sense indicates, you will be misled. Closer inspection reveals that the term "an organization " is an abbreviation of the full term "an organization of social actions." The term "organization" does not itself designate a palpable phenomenon. It refers instead to a related set of ideas that a sociologist invokes to aid him in collecting his thoughts about the ways in which patterns of social actions are related. His statements about social organization describe the territory within which the actions occur; the number of persons who occupy that territory; the characteristics of these persons, like age, sex, biographies, occupation, annual income, and character structure. He tells how these persons are socially related to each other, for he talks of husbands and wives, of bridge partners, of cops and robbers. He describes their activities, and the ways they achieve social access to each other. And like a grand theme either explicitly announced or implicitly assumed, he describes the rules that specify for the actor the use of the area, the numbers of persons who should be in it, the nature of activity, purpose, and feeling allowed, the approved [END PAGE 181] and disapproved means of entrance and exit from affiliative relationships with the persons there. * Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Sociology, University of California at Los Angeles, Calif. SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 3 A number of ideas, then, make up the general concept of "an organization". These are the ideas of territory, of an actor, of numbers, of action, of timing, of rules, of access, and of social relationships. All sociological theories are alike in invoking these ideas. But one particular theory may give them a different specific content, and may combine them differently from another theory. For example, one theory may specify the idea of territory as a geometrical layout, and specifically disregard many other features that a sociologist with different interests would like to stress. The idea of territory may be represented in one theory as real estate; another may cast it as a political jurisdiction. These ideas implicate each other. Thus, a sociologist in deciding what to let them mean in effect decides how he will conceive the patterns of activities to be related. Therefore, because one particular theory may specify these ideas differently from another, theories that differ from one another conceive different meanings of "an organization of activities." Obviously, this means theories that are different, serve different uses. The idea of an organization, therefore, is itself an interpretive technique in sociological inquiry. Consider some examples. Alex Bavelas (1951) of Massachusetts Institute of Technology conceives "an organization of activities" as a communication network. He pays particular attention to the rules that govern who can communicate with whom, and is interested in the speed and efficiency with which groups of five persons who can communicate only over prescribed paths can achieve solutions to tasks that are set for the five persons acting in concert. The persons in the network are narrowly and specifically conceived as task solvers, message writers, and SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 4 message transmitters. More complicated imputations, such as a psychotherapist might use for example, are deliberately disregarded. Because Bavelas describes "communicative paths" mathematically, his "organization" is immensely useful if the investigator is interested in relating certain geometrical properties of interaction to the efficiency with which a set of persons acting in concert can achieve a particular task, or to the distribution among the network's personnel of feelings of group affiliation and rejection. Its particular usefulness comes from the conceptions of paths of communication and positions in these paths which are models of clarity. But while Bavelas' "organization" is useful for some questions, it is not useful for others. For example, if you are interested in why people behave as they do under the pressure of rules, then you may not want to assume that the rules are fixed as Bavelas does. In this case Bavelas' "organization" is of less use than is the so-called "paradigm of social interaction" of Talcott Parsons (1951). Parsons' "organization" places particular stress on the person's perceived situation as a set of mutually anticipated , expected, recollected events. The [END PAGE 182] "rules" that govern their interaction are characterized as particular types of uniformities of these expected and recollected events that the interacting parties treat as maxims of conduct, and that they teach each other, hold each other to respect, and use in controlling each other's actions. In contrast to Bavelas' actor, Parsons' actor can not be conceived except by specifying his situation which includes other people. The two actor and situation, are, so to speak, dialectical counterparts of each other. Thus, what one person expects of another as reward or punishment for his own actions consists, from the point of view of the partner, of the partners' expectations of the actor's SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 5 course of action. A person is a chauffeur thereby, not only on the basis of the service he expects to render the rider, but on the basis of the treatment that he gets in return. Parsons conception of "an organization of activities" is particularly useful for thinking about the phenomena of socialization, deviance, and social control. But Parsons' "organization" in its turn is clumsy if the investigator wishes to study the volume of interaction between large groups of persons located at various distances from each other, like the number of messages that are exchanged between a set of towns and cities. Stuart Dodd (1950) however has developed "organizations" that are specifically designed to handle such phenomena. Dodd's actors contrast with those of both Bavelas and Parsons. For one thing, Dodd's actors are interchangeable with each other. They send messages that are addressed to no person in particular, only to "someone" who is a member of another aggregate. These messages have no meaning; Dodd disregards this feature in his conception of a message. Dodd's actors are engaged in furiously communicating with each other, but the specific content and purposes of the transmission is for his purposes disregarded. We can conclude from these remarks that the sociologist may be useful to the psychiatrist for at least one kind of special competence: the sociologist is a wholesaler in theories of social organization. He has a large number of them on his shelves. Among them the psychiatrist is hound to find many to fit his particular needs. The sociologist's competence with theories of social organization can furnish psychiatrists a second service. The second service comes from the SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 6 sociologist's preference for studying the actions of persons in their organizational settings. Such actions include the troubles that persons are heir to. Sociologists typically look to the features of organized social life, as such, in their attempts to account for who has what kinds of troubles, with what frequencies, with access to what remedies. One might say that the sociologist is interested in the impersonal factors that make for the individual person's troubles. Further, psychiatrists in studying persons in trouble are inclined typically to stress personal biographical factors and the individual's own capacities [END PAGE 183] for managing his own states. The sociologist has available various theories of social organization to tell how biographical factors and the characteristic ways that persons manage their own psychological states are themselves dependent upon the organizational features of the group without respect, necessarily, for the characteristics of the particular individuals involved. This view is frequently a difficult one for psychiatrists to accept. Nevertheless, strange as the view is, students of bureaucratic organization have become startlingly adept at identifying trouble spots in a group when these students know only such things as how access to information, advancement, money, and sponsorship are distributed and controlled in the bureaucracy, or how the succession of leadership is provided for, or the rate of size increase of the group, while knowing very little about the psychiatric biographies of the persons involved nor much about the personalities of the members. (b) Social Reality SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 7 By the study of "social reality," a term sometimes used equivalently with the term "culture," a sociologist means the study of how situations of practical everyday life are socially organized and, as such, are perceived, known, and treated by persons as uniform sequences of actual and potential events which the person assumes that other members of his group know in the same way that he does, and that others, as does he, take for granted. As Alfred Schutz (1955) states it: "(Social reality) ... consists of the objects and occurrences within the socio-cultural world experienced by the common sense thinking of "men living their daily lives among their fellow men, connected with them in manifold relations of interaction. It is the world of cultural objects and social institutions into which we all are born, and within which we have to find our bearings, and with which we have to come to terms." The sociologist is concerned in a variety of ways with making a problem of the feature of persons' "worlds" that they "merely take for granted." A brief comparison of the way sociologists attack this phenomenon with the psychiatrists' interests in the same phenomenon again shows some ways that sociological concepts may be of interest to psychiatrists: a. It is an abiding concern in psychoanalytic investigation to clarify the structure of unconscious activities. The complementary interest on the sociologist's part consists of his equally abiding concern with clarifying the social structuring of highly routinized interpersonal situations. Sociologists refer to this area as the "institutionalized" character of activities and its objects. In pursuing this program, sociologists have developed distinctive terminologies and methods, frequently to the exasperation of others. One such SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 8 distinctive and crucial concept is "common culture." The term figures prominently [END PAGE 184] in sociologists' inquiries and psychiatrists' complaints. There is no easy remedy. The phenomena that the sociologist intends by the term "common culture" is translatable into common sense terms only at the risk of losing the crucial insight that sociologists and their anthropological colleagues have in the last century literally discovered, at considerable cost in effort and reputations. Sociologically speaking, "common culture" refers to socially sanctioned round1 of inference and action that people use in everyday life, and which they assume that other members of the group use in the same way.† Such socially-sanctioned-facts-of-life-that-any-bona-fide-member-ofthe-group-knows depict, among other things: distributions of income, motives of persons, the distributions among persons in the community of honor, competence, responsibility, goodwill, the presence of good and evil purposes behind the apparent workings of things, the actual and potential disorder, misery, poverty, illness, unemployment, trouble in the society as well as the effective remedies, the chances and the reasons that particular persona will be victims, and so on. In order to describe the existence and characteristics of these socially sanctioned grounds of inference and action, sociologists have devised such techniques as questionnaires, polling interviews, content analysis, item sorts, † The phenomenon was pointed to by one of American sociology's heroes, W. I. Thomas, when he stressed the importance for an understanding of a person's behavior of considering that person's "definition of the situation." Thomas laid down the interpretive rule in a famous apothegm, "If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences." SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 9 rules of scale construction, and the like. These devices permit him to survey "common culture" on a mass scale. Such surveys are obtained at the inevitable sacrifice of the exquisite variables that are so apparent in extended conversations with particular persons. But the loss of the minutiae of "common culture" does not sacrifice reality. It is the case instead that a knowledge of fine structure is traded for a knowledge of first order effects that hold over large sectors of the society. Such devices have the further virtue of treating in credible and reproducible fashion such otherwise elusive characteristics of "common culture" as its standardization, the extent of common subscription, its transmissibility, and intra-and inter-personal consistency. Finally, their use has permitted the treatment of these features in a highly rationalized and frequently useable quantitative manner. b. Just as psychiatrists and socioiQ8ists have complementary interests in "unconscious activities," so also do they have complementary interests in "reality oriented" actions. May I refer to them alternately as "rational actions”? Sociologists have described the wide variety of meanings of rational activities found in organizational settings: in studies of industrial, govern- mental, military, business, and educational bureaucracies, of problem solving [END PAGE 185] in groups, of acculturation and cultural marginality, of the situations of upwardly mobile persons, of the criteria of occupational selection and advancement, of the characteristics of Western law, and of various types of leadership. Sometimes these descriptions refer to characteristics of the person's actions; sometimes they refer to organizational features of the group. As examples of the person's activities, sociologists have documented the presence of the extent of the person's concern for the comparability of a present situation SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 10 with those he has known in the past; the economic use of his resources; the degree of error a person will tolerate between an expected outcome and an actual outcome; the extent to which a person engages in conceptualization, analysis, and programming of the conditions for electing alternative courses of action prior to undertaking the action; the nature of a person's concern for the temporal scheduling of a line of action; the fact that a person realizes that he can exercise choice in a situation as well as the situations in which in fact he exercises choice; the empirical adequacy of the means he employs in his pursuit of goals, and many others. The sociologist has described, as well, features of the group as such that correspond to these rational characteristics of the individual person's actions. These have been documented as features of bureaucratic organization: of market control structures; of budgeting and accounting practices; of systems of law; of church organization; of types and uses of authority; of inter- and intraorganizational communications procedures. Not only can sociological inquiries furnish the psychiatrist an elaborated terminology for distinguishing the various phenomena of individual behavior and social structure that the term "rational actions" is used to handle, but sociologists have been concerned to describe the conditions of organized social life under which such phenomena occur. One of these conditions is continually documented in sociological writings: routine as a necessary condition of rational actions. The relationship between routine and rationality is an incongruous one if it is viewed either according to everyday common sense or according to most philosophical teachings. But sociological inquiry accepts almost as a truism that SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 11 the ability of a person to act "rationally,"-i.e. the ability of a person in conducting everyday affairs to calculate, to project alternative plans of action, to select before the actual fall of events the conditions under which he will follow one plan or another, to give priority in a selection of means to their technical efficacy depends upon the fact that the person who is going to "act rationally" or "realistically" must be able literally to take for granted, to take and trust, vast array of features of the social order. In order to treat rationally one-tenth of his situation that, like an iceberg, appears above the water, he must be able to treat the nine-tenths that lies below as an unquestioned, and even more interestingly as an unquestionable, [END PAGE 186] background of matters that are demonstrably relevant to his calculations but which appear without being noticed.‡ The sociologist talks about these trusted, taken for granted, background features of the person's situation, i.e., the routine aspects of the situation that permit "rational actions," as "mores, and "folkways." Psychiatrists commonly consider these habitual, traditionalized, socially sanctioned practices in their diagnoses. Because these sanctioned practices vary a great deal as one goes from one ethnic group, for example, to another, a knowledge of them aids in discriminating "bizarre practices" that are features of psychopathology from those that are normal to the patient’s ingroup ‡ In a famous discussion of the normative background of activities, the French sociologist, Emile Durkheim, made much of the point that the validity and understandability of the stated terms of a contract depended upon its unstated terms that the contracting parties took for granted as binding upon their actions. "The Division of Labor," translated by George Simpson, The Free Press, Glencoe, Illinois, 1947. SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 12 But a further use of these “mores” is suggested here. For sociologists the “mores” depict the ways in which routine is a condition for the appearance of “rational actions,” or in psychiatric jargon, for the operativeness of the "reality principle." The mores may be used to show how the stability of social routines is a condition which enables persons to recognize each other’s actions, beliefs, aspirations, feelings, and the like as reasonable, normal, legitimate, understandable, and realistic. II. The kind of work that sociologists engage in when attacking a problem (a) Interpretive Rules Because sociologists subject to scientific contemplation those matters whose value and relevance we are inclined in everyday affairs to take for granted, sociologists have in their theories, which are interpretive rules for ordering their impressions and observations, devices for appreciating the incongruous character of everyday life. Several devices of interpretation are available to sociologists to aid them to scan a familiar world in upside-downfashion. I want to mention one: the conception of the "homeostatic" characteristics of group interaction. There are many ways of conceiving the logically necessary connections between actual observations. A prominent one for sociologists conceives their related character under the scheme of a "homeostatic system." Such a scheme of interpretation calls to our attention the features of self-regulation, selfmodification, and self-maintenance. The writings of Talcott Parsons (1951) have SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 13 been explicitly concerned with the tasks of conceiving homeostatic relationships realistically with respect to the phenomena of human conduct. [END PAGE 187] Parsons' task in theorizing is this: How to conceive the necessary relationships between the patterns of social interaction while providing first for the perspective of the participant , and, second, while retaining a respect for the phenomena of "social reality." Parsons undertook the problem by investigating the relationships between personality systems and social systems. In a recent essay, "The Superego and the Theory of Social Systems,' Parsons elected the solution of revising the content of the superego to include the internalization of all culture. As a consequence of this decision, a new accent is placed upon the behavioral details that the psychoanalysts have documented as the mechanisms of ego defense. The effect of Parsons' formulation is to treat the mechanisms of defense as an open list of "devices" whereby a sensible shape of the world is continually accomplished by the actor, with the features of the group providing the conditions for, as well as the limitations upon, the ways of handling personal strains, past, present, and prospective. By not assuming the fact of social order, but asking in the first instance how it is constituted and maintained [which Parsons refers to in a concern for the mechanisms of social deviation and social control), Parsons does not start with the defense mechanisms, but instead seeks to discover them. Programmatically, his procedure is to consider a viable group and to ask for the features that contribute to its viability. The scheme provides psychiatrists a way of thinking about the social consequences of the defense mechanisms. SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 14 (b) Conceptual Play In preparing a question for sociological treatment, sociologists make use of several techniques that can properly be referred to as techniques of conceptual play. By conceptual play is meant that the investigator undertakes the solution to a problem by altering imaginatively the features of the problematic situation and then following through the consequences of this alteration without suspending a respect for the basic rules of his discipline. Many techniques of conceptual play arc solutions to the enduring problem of establishing comparability in the data. The sociologist seeks methods for describing human experiences instances of a class of recurrent and typical events. With increasing frequency, this problem is being solved through the use of control groups, comparative statistics, sampling procedures, randomizing techniques, and the like. Immense importance for the credible use of schemes of inference resides in them, for they permit the investigator to state his findings as generalizations which carry along with them rational estimates of their erroneous character that are related to the procedures of the inquiry and thereby to the reproducibility of the claimed findings. Sociologists are indeed increasingly occupied with "counting and measuring." Psychiatrists, [END PAGE 188] generally, find such behavior on the sociologist's part offensive. But unless psychiatrists appreciate the sociologist's concern for counting and measuring in the light of the tasks of comparison that both sociologists and psychiatrists must necessarily and unavoidably address, psychiatrists will make foolish complaints, and, worse, will overlook a most useful resource that their sociological colleagues can furnish. SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 15 But statistical techniques of conceptual play do not differ in principle from one discipline to another. By comparison, there are several techniques to facilitate the task of comparison that are particular to sociology. The mental experiment: Frequently referred to as the "mental experiment" is a device more accurately called the method of "free variation." The method is exemplified in the following excerpt from Karl Mannheim's essay, "The Sociological Problems of Generations (Mannheim, 1952): ''The best way to appreciate which features of social life result from the existence of generations is to make the experiment of imagining what the social life of man would be like if one generation lived on forever and none followed to replace it. In contrast to such a Utopian imaginary society, our own has the following characteristics: a. New participants in the cultural process are emerging. (while) b. Former participants in that process are continually disappearing. c. Members of any one generation can participate only in a temporally limited section of the historical process. d. It is therefore necessary continually to transmit the accumulated cultural heritage. e. The transition from generation to generation is a continuous process. Although it may put me in trouble with my fellow sociologists to say so, the principle of the method can be seen in any of the better varieties of science fiction that elaborate the consequences of an imagined change of some fundamental feature of the social order, while the imaginer retains a respect for sociological fact. The procedure produces an "objectively possible" sociological state of affairs that can be used as a standard for SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 16 comparison with a known state of affairs in order to evoke properties that are otherwise unseen or difficult to grasp. The method becomes of interest to psychiatrists because one need not begin with a vision of a person or a social setting constructed merely out of imagination. Instead, one may begin with a situation that is known in a vastly comprehensive manner and retain the entirety of its actual detail. The trick consists of prefacing the entire description with the theoretical fiat, ."Let it be that..." That is to say, everything is retained as it was known before, let us say the details of a case history, but with the important change of meaning that accompanies the fact that its empirical accuracy is suspended, "officially disregarded." The material is addressed by changing the aspect of "It is so..." to "Let it be that it is so..." [END PAGE 189] When applied to psychiatric work , the method calls to the psychotherapist’s attention those respects in which the patient is explicitly assumed to be comparable to all other patients defined as a class by the things that the particular patient has done and said. The technique has the effect of multiplying the amount of organized behavioral detail that may be used for comparison by substituting for the procedurally sterile concept of the "actual patient" a set of alternative ways of appreciating the typical character of the particular patient 's behavior. The natural metaphor: A useful form of the method of free variation is found in a technique that is known around the Department of Sociology at the University of Chicago where it was developed as the use of "natural metaphors." SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 17 By this is meant that there are formal similarities in the situations of persons located at different places in the social order. These structurally repeated situations, though they may be known to the participants by different names, are organizationally identical. The participant's ways of describing their own situations may be used as the metaphor or model for appreciating the formally identical features in the situations of others. For example, what the showman calls "singing," the Jewish waiter calls "staging," the psychologist calls "directed activity." All three terms refer to the actions that a person engages in who seeks some advantage from another, and who must capture it within the limited opportunities of the immediate interaction by not only accomplishing a task but by communicating to the other person that a task is being accomplished. Irving Goffman of the Laboratory for Socioenvironmental Studies of the National Institute of Mental Health has made most extensive and convincing use of the technique. In one paper (Goffman, 1952) he drew upon the confidence game for the concept, "cooling the mark out." Among professional confidence men provision must be made as part of the play to reconcile the victim (the "mark") to the loss that he has suffered, and to accomplish this in such a way that the victim does not interfere with the continued operations of the game. Giving his paper the subtitle, "Some Aspects of Adaptation to Failure," Goffman writes: "An expectation may finally prove false even though it has been possible to sustain it for a long time and even though the operator acted in good faith. (As a routine feature of the society's operations) a large number of persons may as a normal course be involuntarily deprived of a position or a commitment or an SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 18 involvement and made in return something that is considered a lesser thing to be. Such loss may be taken as a reflection on the loser and is of interest because to the extent that the loss requires the severance of a commitment, severe humiliation is involved . Disappointment of a reasonable expectation as well as the disappointment of a misguided one creates a need for consolation. Cooling the mark out is a theme in a very basic social story." [END PAGE 190] Goffman then describes several situations of social life in which it becomes necessary on important and repeated occasions to console the victim, to "cool the mark out." He asks three questions: How can they be made to accept the great injury and to carry on without interfering with the continued operations of the system? How to deal with those who refuse consolation? And what arrangements are made by operators and victims to avoid entirely the distasteful and upsetting business of consolation? The cogency of Goffman's particular application of this method for sociologists and psychiatrists alike need not be elaborated. Both have routine professional dealings with the risks and consequences of failing and failure. The praxeological rule of the sociological attitude: Goffman is concerned with failing and failure as matters of technical interest. He treats these matters in much the same way as does the confidence man, from whom he borrows the image of failure. In treating failure as a matter of technical interest, Goffman is honoring a rule that is definitive of the sociological attitude. By demonstrating this rule and giving some applications, another technique of conceptual play can be seen. Although the rule is used by sociologists, it is without a name. For convenience, I shall call it the praxeological rule. SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 19 As the program of praxeology was recently described it consists of the search for similarities of successful methods in many different domains of activity. Praxeology seeks to formulate statements of method, and to extend their generality, seeking as wide a domain of applicability as possible. The theory of games and scientific methodology are instances of praxeological disciplines. Insofar as a praxeological rule may be said to constitute a definitive feature of the sociological attitude, the following is being referred to. Accounts by sociologists of the conditions under which a phenomenon occurs may be mapped point for point into the terms of strategies that persons follow whereby, knowingly or not, they achieve the pay-off represented in the value of the variable under study. The praxeological rule states that any and all properties whatsoever of a social system that a sociologist might elect to study and account for are to be treated as technical values which the personnel of the system achieve by their actual modes of play. When it is the determinants of a given rate of output in an industrial plant that is of concern, the applicability of the rule is fairly familiar. Even common sense does not boggle over it. But the same rule holds for the ways persons are distributed by class or income or voting preferences. It holds for the simple or intricate character of the division of labor; for the differential risks by class of various mental illnesses; for the stability of suicide rates; and for the way symptoms cluster into discriminable clinical entities. Several applications of the rule that are particularly relevant to the interests of psychiatrists can be illustratively cited. [END PAGE 191] 1. Merton's (1949) theory of anomie and social structure may be stated "praxeologically" as follows: If you wish to multiply the SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 20 frequency in a society of frustration, psychosocial isolation, delinquency, alienation, compulsive conformity, and dissent then socialize the society's members so that there is uniform respect for ultimately valued goals while you routinely and differentially deprive the members of the legitimate means for achieving them. 2. The relationship that Levy (1952) finds between the disparity in the loci of power and responsibility and the stability of a social system can be stated in the following way: To multiply the instability of a set of activities, deprive persons of the means for controlling the conditions of an outcome while holding them to account as causal agents of the outcome. 3. Myrdal's (1944) formulation of the "cyclical" effect in the maintenance of anti-Negro discrimination would run: To conserve resistance to an attempt to alter a feature of the social order, reinforce the expectancy for any particular person that others respect this feature, and have the person treat the beliefs that he imputes to others as features of the social order so that he will respect the moral character of limited tests of opinion. 4. Lindesmith's (1947) theory of the determinants of drug addicition would be stated as follows: To increase the rate of drug addiction, teach persons receiving the drug which symptoms of distress are due to the withdrawal of the drug. The use of the praxeological rule has the virtue of drawing attention away from the search for impersonal "causal laws" of human action, framed in terms of the determinants of an effect, in favor of stating the operations that an SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 21 investigator conceives the actors to be performing upon a system of relationships to produce the state the sociologist is interested in. III. "Understanding" as a Technique For Studying Human Affairs I want to conclude with some remarks on "understanding" as it is used by sociologists as a method for studying human affairs. As a method for solving problems of sociological inquiry, "understanding" has several distinct meanings (Shutz, 1955). I shall comment only one of these meanings: the documentary method. I cite this method, not because it is the sociologist's to sell to psychiatrists, but because it is a method shared by both and is even inexorably binding upon the investigative efforts of both. Further, it is the method not only of psychiatrists and sociologists, but of the man in everyday life whose experiences are their abiding objects of study. By citing the method, I hope to show that their differences are not as great as the partisans would hope, though this does not mean of course that they can therefore dwell in peace. According to Karl Mannheim (1952) the documentary method involves the [END PAGE 192] search for "... an identical, homologous pattern underlying a vast variety of totally different realizations of meaning." It involves the treatment of a sign's referrent as "the document of ... ," as "pointing to" an underlying pattern. Not only is the underlying pattern derived from its individual documentary evidences, but the individual documentary evidences are in their turn interpreted on the basis of "what we know" about the underlying pattern. This procedure, as Mannheim correctly stressed, is peculiar to the social sciences. One kind of documentary procedure that particularly concerns psychiatrists has been variously referred to as "sympathetic introspection," SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 22 "method of insight," "intuitive feeling," "method of intuition," "interpretive method," "clinical method," "empathic understanding," and so on. Attempts by sociologists to identify something called "interpretive sociology" involve the reference to this procedure as the basis for encountering and warranting its findings. Applications of documentary methods in sociological research are widespread and perhaps ineradicable. Consider the variety of things that sociologists know and describe in a documentary manner§ To begin with, there are the extensive descriptions of cultural orientations, cultural themes, value orientations, value standards, styles of life, life organizations, national character, all of which are realized as to their specific characteristics through a method whereby evidences are used to "document" the "underlying pattern." Just as the documentary method is used when the psychiatrist treats the patient's self-diagnosis as a symptom of his illness rather than as a correct identification of his illness, the sociologist , no less than the psychiatrist, is concerned with the "motivated character" of an actor's accounts of what is the case with him and with others or with features of the society. While sociologists have been reluctant to treat a Weltanschauung, or "the spirit of an epoch," as a legitimate object for inquiry, they have warmed to the descriptions of "group atmosphere," of the state of consensus, of "normal functioning," and "normal operations," and of conditions of group viability and equilibrium. § Much of the following discussion indebted to Mannheim’s (1952) essay, “On the interpretation of Weltanschauung." SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 23 Still another application is found in those accounts which are warranted by the criterion of comprehensive description as contrasted with a description that is adequate to the logical requirements of a specific theoretical representation of the situation under examination. The method is exemplified again when the formal features of a situation are used to epitomize the object under assessment. Just as one may say, "Isn't that just like Harry," one may use some feature of a group to stand for the group itself. [END PAGE 193] It is the documentary method that is used when one finds evidences of the other person's common sense, or evidences of his potentialities, but before everything, the evidences of "what the other person has in mind." The documentary method is a way of realizing the unity of a biography. The work of historicizing past events, either for a particular person or for a collectivity, consists of the application of the documentary method to the task of selecting and ordering past occurences. It is necessary to point out, too, that events in daily life are known through their documentary meanings. Consider a commonplace example. When coming upon a basket of apples, we treat it as a basket of apples, despite the fact that a small fraction of the specifications of "a basket of apples" serve as the test and document of the "basket of apples." By contrast, one would have to consider the distrustful procedure whereby one would make " 𝑛(𝑛−1) 2 comparisons of the apples in the basket" the sense of the "basket of apples." What holds for our treatment of a basket of apples holds more generally. The sociologist sees evidences that persons are forever attesting the normality of the situations in which they participate. Whole orders of actions and personnel SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 24 are treated by the actor under the critically important aspect of "the sameness of the scene," i.e. its comparability to situations known in the past, despite the variability of behavioral appearances and the continual alterations of props and scenery. The product of the actor's use of the documentary method is the constancy of relationships between an actor and his changing scenes of activity. Finally, the method can be cited as a prominent part of the work that persons engage in whereby they maintain themselves and each other as the same persons, i.e. as temporally homogeneous products. The sociologist is found of citing as an important variable of social order the social judgements that the member of a group employ whereby they retain their images of each other as the same and valuable people. According to this conception, the self, as a homogeneous product for other persons, is the outcome of continual and careful management. It is in terms such as these that the sociologist is concerned with conventionality and conformity, with status systems, with the paradoxical relationship between individual choice and the standard products of concerted action. All of these phenomena presuppose a set of actors who are conceived by the sociologist to know the scene around them in a documentary manner, i.e. to know the scenes around them in the ways that they furnish the actor documentary evidence of types of persons, their motives, feelings, relationships, worth, competence, and so on. The use of the documentary method is therefore intimately related to the phenomenon of trust. Through the documentary method, persons are enabled to treat such properties of a scene as invariants despite continual alterations of actual appearances. [END PAGE 194] All scientific disciplines have their great chronic problems to which the methods of the particular discipline represent solutions. A prominent problem in SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 25 sociology and the social sciences generally is that of achieving a unified conception of an object that has as its specific formal property that its present character will have been decided by a future outcome. The documentary method shows its uses not only as a unique instrument of the social sciences, but as the only method so far capable of handling events having this peculiar time structure. The documentary method consists essentially of the retrospectiveprospective reading of a present outcome so as to maintain the identicality of the object through temporal and circumstantial alterations. Such method seems to be an inextricable feature of situations in which the rules that govern communicative exchanges create situations in which actions must be taken despite the fact of incomplete information. Psychiatrists, sociologists, and persons whose psychiatric and sociological judgements are governed by the interests of everyday life are in this respect in identical situations, and have in common a prevailing and identical method for coming to terms with them. It is obvious that they should therefore have much to teach each other. SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 26 References Bavelas, Alex. 1951. Communication patterns in task-oriented groups. The Policy Sciences, edited by Daniel Lerner and Harold D. Lasswell. Stanford University Press, Stanford, Calif. Parsons, Talcott. 1951. The social system. The Free Press, Glencoe. Ill. Dodd, Stuart. The interactance hypothesis, a gravity model fitting physical masses and human groups. Am. Soc. Rev., April, 1950:245-256. Schutz, Alfred . Concept and theory formation in the social sciences. J. of Phil ., April 24, 1955:257-273. Parsons, Talcott. 1953. The superego and the theory of social systems. Working Papers in the Theory of Action. Talcott Parsons, Robert F. Bales, and Edward Shils. The Free Press, Glencoe. Ill. Mannheim, Karl. 1952. The problem of generations. In Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge, translated and edited by Paul Kecskemeti, Oxford University Press, N.Y. Coffman, Irving. On cooling the mark out, some aspects of adaptation to failure. Psychiat., November, 1952:451-463. Hiz, Henry. Kotarbinski's praxeology., Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, December , 1954:238-243. SOME SOCIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS AND METHODS FOR PSYCHIATRISTS 27 Merton, Robert K . 1949. Social structure and anomic, Social Theory and Social Structure. The Free Press, Glencoe, Ill. Levy, Marion J. , JR. 1952. The structure of society, Princeton Univ . Press, Princeton , N.J . Myrdal, Gunnar. 1944. An American dilemma. Harper and Brothers, N.Y. Lindesmith, Alfred, R. 1947. Opiate addition. Principia Press, Bloomington, Ill. Mannheim, Karl. 1952. On the interpretation of Weltanschauung . Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge, translated and edited by Paul Kecskemeti, Oxford University Press, N .Y. [END PAGE 195]