Barth_Fall2014 - MINDS@UW Home

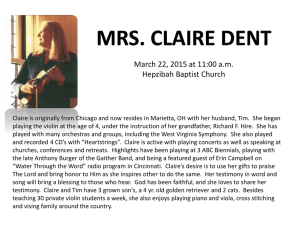

advertisement