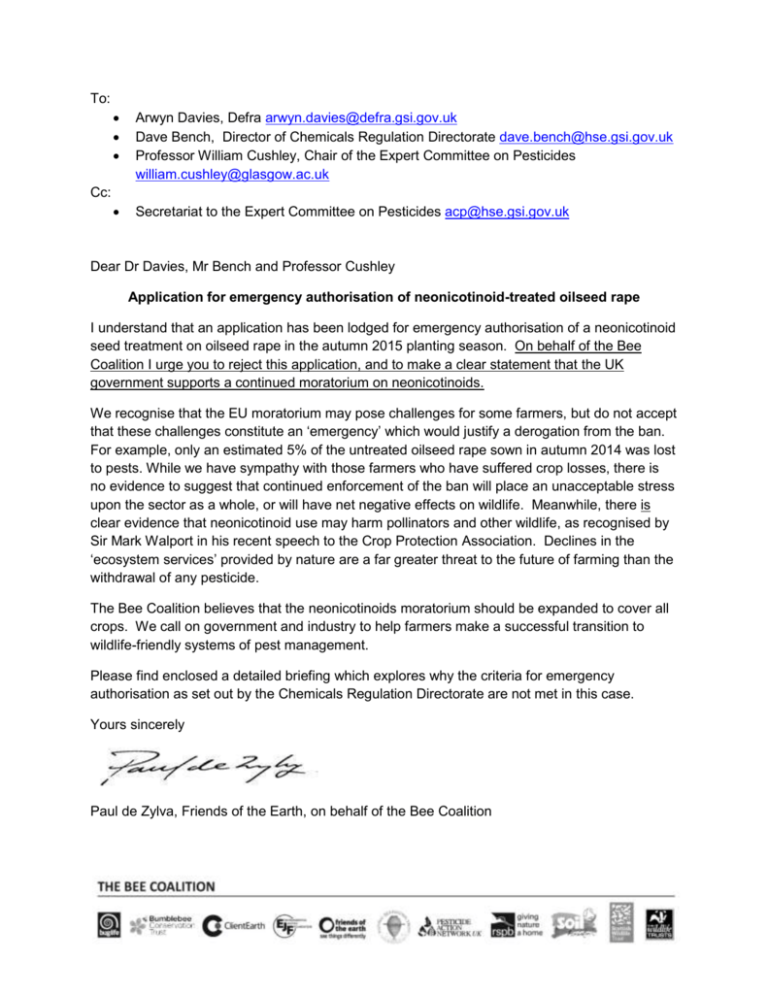

To read the Bee Coalition`s letter to in response to the NFU

advertisement

To: Arwyn Davies, Defra arwyn.davies@defra.gsi.gov.uk Dave Bench, Director of Chemicals Regulation Directorate dave.bench@hse.gsi.gov.uk Professor William Cushley, Chair of the Expert Committee on Pesticides william.cushley@glasgow.ac.uk Secretariat to the Expert Committee on Pesticides acp@hse.gsi.gov.uk Cc: Dear Dr Davies, Mr Bench and Professor Cushley Application for emergency authorisation of neonicotinoid-treated oilseed rape I understand that an application has been lodged for emergency authorisation of a neonicotinoid seed treatment on oilseed rape in the autumn 2015 planting season. On behalf of the Bee Coalition I urge you to reject this application, and to make a clear statement that the UK government supports a continued moratorium on neonicotinoids. We recognise that the EU moratorium may pose challenges for some farmers, but do not accept that these challenges constitute an ‘emergency’ which would justify a derogation from the ban. For example, only an estimated 5% of the untreated oilseed rape sown in autumn 2014 was lost to pests. While we have sympathy with those farmers who have suffered crop losses, there is no evidence to suggest that continued enforcement of the ban will place an unacceptable stress upon the sector as a whole, or will have net negative effects on wildlife. Meanwhile, there is clear evidence that neonicotinoid use may harm pollinators and other wildlife, as recognised by Sir Mark Walport in his recent speech to the Crop Protection Association. Declines in the ‘ecosystem services’ provided by nature are a far greater threat to the future of farming than the withdrawal of any pesticide. The Bee Coalition believes that the neonicotinoids moratorium should be expanded to cover all crops. We call on government and industry to help farmers make a successful transition to wildlife-friendly systems of pest management. Please find enclosed a detailed briefing which explores why the criteria for emergency authorisation as set out by the Chemicals Regulation Directorate are not met in this case. Yours sincerely Paul de Zylva, Friends of the Earth, on behalf of the Bee Coalition Bee Coalition briefing May 2015: impacts of the neonicotinoids moratorium on oilseed rape growing This briefing critically examines some of the arguments put forward in favour of granting an emergency authorisation for the use of neonicotinoids on oilseed rape (OSR). 1) In the absence of an emergency authorisation, farmers may reduce the area of OSR they plant because of concerns that they will not be able to control insect pests adequately. OSR was first introduced to the UK in the 1970s1. The total area of the crop was 269 thousand ha by 1984, rising to a record high of 756 thousand ha in 2012. The area has decreased for the last two years and was 675 thousand ha for the 2014 harvest2. The total area planted in 2014 (for the 2015 harvest) was estimated at 649 thousand ha3. According to an HGCA survey of 1,300 farmers, about 11% of farmers would have planted more OSR if neonicotinoid seed treatments had been available. When scaled up to a national level, this result indicates that an additional 38 thousand ha of OSR would have been sown in 2014 had neonicotinoids been available4. Many factors affect a farmer’s decision to grow OSR, such as market price/ profit margin compared to other crops. This in turn is affected by total supply and demand in the UK, EU and worldwide, as well as cost and availability of inputs5,6 (it is relevant to note that UK oilseed prices dropped between 2012 and 20147). It is therefore not possible to definitively state how much of an effect the neonicotinoid ban has had or will had, but it is probably having some effect. What are the implications of a declining area of OSR in the UK? OSR is primarily grown as a break crop, increasing the yield of the following cereal crop, and providing an opportunity to control grass weeds8. Those farmers who choose to reduce their planting of OSR could grow an alternative break crop such as field beans or introduce a fallow period into the rotation9. HGCA has highlighted that OSR yields may be dropping because farmers are growing the crop too frequently within the rotation10, indicating that there may be agronomic benefits of decreasing the amount of OSR grown. Any significant decrease in production of OSR in the UK (which depends both on area of OSR grown and yield per hectare, see below) would affect the UK processing industry and possibly the UK biodiesel sector11. A United Oilseeds spokesperson has predicted production of at least 2.2m tonnes in 201512 (for context, production over the last 10 years has ranged between 1.9m tonnes and 2.8m tonnes13). The impacts on individual farm businesses, and on the local environment and wildlife, of growing less OSR would depend very much on what farmers use the land for instead. Conclusion: the area of OSR planted will continue to fluctuate in response to a range of drivers, of which the neonicotinoids ban may well be one. Evidence so far does not lead us to expect a major shock to the industry from a continuation of the moratorium. 2) Increased pest pressure may lead to lower yields of OSR per hectare sown. Neonicotinoid seed treatment is recommended to reduce damage by flea beetle species and Cabbage Stem Flea Beetle (CSFB) in the early stages of crop growth, and can also provide early season control of Peach-potato Aphid14. CSFB is considered a major pest of OSR. Large numbers of CSFB adults feeding in the autumn can kill plants, occasionally resulting in total crop failure. Larval feeding in the stems and petioles reduces vigour and can cause severe damage, which may lead to stunting or plant death15. Autumn 2014 was the first planting season for winter OSR without neonicotinoids. According to a survey by HGCA, an estimated 2.7% (18,000ha) of the area sown nationally was completely lost, mostly because of CSFB damage, and had to be re-drilled with OSR or another crop. Over half the crop nationally was either not significantly affected by CSFB or had already grown past the vulnerable stage at the time the assessment was carried out. Significant regional variation in damage from CSFB was noticeable, but overall HGCA concluded that the impacts had been ‘modest’.16 A later assessment put the area lost at 5%, with 1.5% successfully redrilled17. This crop will be harvested in summer 2015 so the final yields are not yet known, but the farming media has reported that the crop is ‘looking good’18. There is considerable uncertainty surrounding the implications of growing OSR without neonicotinoids, including what level of pest control is achievable without neonicotinoid seed treatments, and to what extent OSR seedlings can withstand pest damage at various growth stages. An HGCA project aims to answer these questions and others, and is expected to report by the end of May 201519. A FERA paper, which we understand will compare yields of treated and untreated OSR between 1990 and 2010, is currently in review (personal communication). Some research on other crops and elsewhere in the world has failed to find any yield benefit of neonicotinoid seed treatments, or any yield penalty from ceasing to use them20. A difficulty in demonstrating yield or profitability benefits is that seed treatments are applied each year before the level of pest pressure is known. For a given crop, it is difficult or impossible to know whether the seed treatment in a given year a) saved the crop from significant damage which would otherwise have occurred, or b) was unnecessary. This is discussed further below. It is important to note that yields of OSR (and other crops) are also dependent to varying degrees on ‘ecosystem services’ provided by biodiversity, such as pollination, pest control and soil formation. For example, insect pollination is known to enhance oilseed rape yields21. Research has highlighted possible impacts of neonicotinoid use on these ecosystem services22, and although no attempt has been made to quantify any effect on crop yields, this needs to be factored in. Conclusion: we are not aware that any clear evidence has yet been published on the effect of neonicotinoid seed treatment on OSR yields in the UK. Experiences in other countries indicate that yields can be maintained in the absence of neonicotinoids. 3) Alternative pest management strategies adopted by farmers may prove equally or more damaging to pollinator populations. Non-chemical approaches to managing OSR pests are available, including management which favours natural enemies and timing of operations to avoid vulnerable stages of crop growth coinciding with likely pest attacks, as well as alternative products such as biopesticides23,24. Other than neonicotinoids, the only chemical currently available for controlling CSFB and other flea beetle species is foliar sprays of pyrethroid insecticides25. Resistance to pyrethroids is now widespread among CSFB populations, decreasing the effectiveness of these sprays26. Pyrethroids, like all pesticides, can potentially cause environmental harm, and they are toxic to bees and other non-target organisms. We are not aware of any studies directly comparing possible impacts on pollinators of neonicotinoid seed treatments and pyrethroid sprays, although data is available on factors such as persistence, mobility and toxicity of each group of chemicals. It should be noted that pyrethroid products, like neonicotinoids, have been assessed and approved by the EU and the UK as not posing an unacceptable risk. The current debate clearly calls into question the thoroughness of this risk assessment process. The impacts of a pesticide depend both on its intrinsic properties and the way in which it is used. Claims that seed treatments are more precisely targeted to the crop than sprays are called into question by the finding that only 1.6 - 20% of the active substance in a seed coating is actually absorbed by the crop27. The remainder can end up in the soil, in field margin vegetation, or in waterways, where a variety of wildlife can come into contact with it. Another key point is that seed treatments are not ‘targeted’ to pest outbreaks: they are applied before it is known whether there will be a pest problem. This is in clear contravention of the principles of Integrated Pest Management. Finally, it is important to stress that neonicotinoid seed treatments have been used alongside, not instead of, pyrethroid sprays. Neonicotinoid seed treatments were first used on oilseed crops in 2002. In 2001, a total of 10,051kg of pyrethroids were applied to oilseed crops in Great Britain, and the total area treatedi was 522,977 ha. By 2011, neonicotinoid use on oilseed crops had increased significantly (71% of OSR was treated28), but pyrethroid use had risen to 24,396kg over 1.37 million ha. The most commonly applied pyrethroid on OSR is cypermethrin. Most crops are treated once, but some are treated two or more times. There is some evidence that multiple treatments may have become less common since neonicotinoids were introduced, which might be expected if neonicotinoids are successfully controlling pests early in the season29. At best the introduction of neonicotinoid seed treatments may have reduced the use of pyrethroids: these older pesticides have certainly not been replaced. Conclusion: Neonicotinoids have been used alongside, not instead of, older chemicals such as pyrethroids. It is not clear to what extent the ban on neonicotinoids will increase the need for i Area treated refers to the active substance treated area. This is the basic area treated by each active substance, multiplied by the number of times the area was treated. If a field of 3 ha is treated 4 times, the area treated is 12 ha. use of these other chemicals. More effort should be put into researching and promoting nonchemical alternatives. References 1ADAS (2009) Future of UK winter oilseed rape production Defra (2014) Farming Statistics: Final crop areas, yields, livestock populations and agricultural workforce at June 2014 - United Kingdom 3 HGCA (2014) Early bird survey 4 HGCA (2015) Project Report No. 541: Assessing the impact of the restrictions on the use of neonicotinoid seed treatments 5 HGCA (2014) Oilseed rape guide 6 ADAS (2009) Future of UK winter oilseed rape production 7 HGCA (2014) Outlook for global oilseed prices 8 HGCA (2014) Oilseed rape guide 9 ADAS (2009) Future of UK winter oilseed rape production 10 HGCA (2014) Oilseed rape guide 11 ADAS (2009) Future of UK winter oilseed rape production 12 As reported in Farmers Weekly, 16th April 2015 http://www.fwi.co.uk/arable/oilseed-rape-looks-good-with-cropforecast-at-2-2m-tonnes.htm 13 Defra: UK cereal and oilseed area, yield and production (accessed May 2015). 14 Cruiser product label (accessed May 2015) 15 AHDB (2014) Encyclopedia of pests and natural enemies in field crops 16 ADAS (2014) Cabbage stem flea beetle snapshot assessment – incidence and severity at end September 2014. 17 HGCA (2015) Neonicotinoid restrictions: Impact on OSR planting area and CSFB larvae activity 18 As reported in Farmers Weekly, 16th April 2015 http://www.fwi.co.uk/arable/oilseed-rape-looks-good-with-cropforecast-at-2-2m-tonnes.htm 19 HGCA project 214-0000: Maximising control of cabbage stem flea beetles (CSFB) without neonicotinoid seed treatments. 20 Center for Food Safety (2014) Heavy costs: weighing the value of neonicotinoid seed treatments in agriculture. 21 Bommarco, R. et al. (2012) Insect pollination enhances seed yield, quality, and market value in oilseed rape. Oecologia 169:1025-32 22 Chagnon, M. et al. (2015) Risks of large-scale use of systemic insecticides to ecosystem functioning and services. Environ Sci Pollut Res 22:119–134 23 AHDB (2014) Encyclopedia of pests and natural enemies in field crops 24 Friends of the Earth (2013) Briefing: Alternatives to neonicotinoids. 25 HGCA (2013) Neonicotinoids: key messages 26 HGCA (2014) CSFB: resistance widespread. Accessed May 2015. 27 Sur, R. & Stork, A. (2003) Uptake, translocation and metabolism of imidacloprid in plants. Bulletin of Insectology, 56, 35–40 28 HGCA (2013) Neonicotinoids: key messages 29 Data source: FERA pesticide usage statistics 2