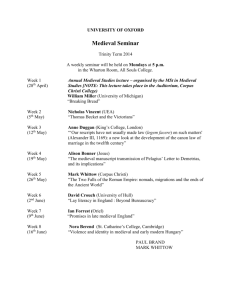

Medieval English Society

advertisement

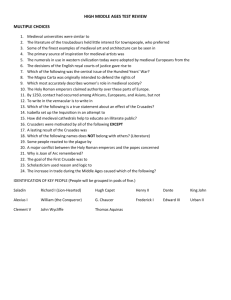

MEDIEVAL ENGLISH SOCIETY http://history.wisc.edu/sommerville/123/123%2013%20Society.htm Domesday Book provides a wealth of information about English society in 1086. It lists about 13,000 towns, villages and tiny hamlets. The basic unit in Domesday Book was the manor - since this showed who owned the land and controlled its inhabitants. At the time of Domesday Book, more than 90 per cent of the English population (of about two million) lived in the countryside. Even with the vast mass of the population engaged in agriculture, almost all the cultivable land had to be farmed because output was so low - about four times the amount of seed sown. (To feed one person for a year on wheat required about two acres of land - today's yields would produce the same from 1/3 of an acre.) The average holding of a peasant family during the 14th century was about 12 to 15 acres, but many poor cottars survived on less than five acres - supplementing their income by working as laborers. Wheat was preferred for human food consumption, but other crops were also sown: barley - the basic constituent of ale; oats - for the livestock that manured the land; peas - both as a source of protein and because they increased the soil's fertility if alternated with grain crops. 1 Fish also played an important part in the medieval English diet. No place in England is more than about 100 miles from the sea, and its many rivers also provided freshwater fish. The Cuckoo Song [Summer is arriving, Sumer is icumen in, Lhude sing cuccu! Groweth sed, and bloweth med, And springeth the wude nu — Sing cuccu! Awe bleteth afer lomb, Lhouth after calve cu; Bulluc sterteth, bucke verteth, Murie sing cuccu! Cuccu, cuccu, well singes thu, cuccu: Loudly sing cuckoo! Seeds are growing, meadows blowing, And woods renewing — Sing cuckoo. Ewes bleat after lambs, Cows low for calves; Bullocks are shying, bucks are leaping, Merrily sing cuckoo. Cuckoo, cuckoo; well may you sing cuckoo, You should never stop singing cuckoo]. Ne swike thu naver nu; Sing cuccu, nu, sing cuccu, Sing cuccu, sing cuccu, nu! One of the earliest surviving examples of English verse, dating from the early 13th century, The Cuckoo song shows the rural concerns of an agricultural country. Social classes Land and social structure in Medieval England. [The column on the left shows the approximate proportion in the population; the column on the right, the rough proportion of land held or farmed (though not necessarily owned; villeins held their land from a lord who owned it); slaves have no right hand column as they had no land] 2 The Free At the top of the English social scale stood the king and nobility. Senior churchmen (abbots and bishops) were also barons with noble status. About 200 of these men formed England's ruling elite. Crown, nobility and church owned about 75% of English land. Immediately below the nobility were knights. Knighthood was not hereditary; instead, men were made knights as a reward for outstanding service or because they had become wealthy enough. (By the 14th century, there were about 1,000 knights, owning land worth on average ₤40 per annum.) [Until the later 14th century, noblemen and knights spoke a different language from the common people - an increasingly corrupt form of French, quite unlike the basically Germanic speech illustrated in The Cuckoo Song.] Effigy of a Suffolk knight c. 1330 The other class of freemen were "sokemen" (or socmen.) Roughly one in six of the population were sokemen, and they owned about twenty per cent of the land. They were especially numerous in East Anglia. Sokemen held in socage; they had security of tenure provided they carried out certain defined services often including light labor services and paying a fixed rent. Their land was heritable. The Unfree The largest class of the population were villani. (Those born to servile status were also called nativi.) About four in ten people were villani tied to the land. They did not own the land but farmed their own holdings (about 45 per cent of all English land,) which they were allowed to occupy in exchange for labor services on the landowner's demesne. The exact services required from villani varied in accordance with local customs and agreements. A common arrangement was three days work each week (more in harvest time). During the 12th Century the villani were keen to have their labor services commuted to money rents, but labor services remained widespread. A lower class of villeins were known as bordars or cottars. These occupied very small plots of land for personal use, which like the villani 3 they did not own, but for which they had to pay rent and/or labor services. Although they constituted about one third of the population, bordars only occupied about five per cent of the land. At the very bottom of the social scale were slaves who owned no land at all. These constituted slightly less than one in ten of the population at the time of Domesday Book. During the 12th Century many of these slaves were given holdings and became bordars. Social and economic change meant that these classes were far from fixed - villeins could buy free land, and freemen could slip into villeinage. In the course of the Middle Ages the tendency was for the peasants to become freer but poorer - as population expansion outstripped the growth of agricultural productivity, reducing the size of average landholdings; this also had the effect of reducing the price of hired labor; lords could find it more efficient to hire cheap labor (paid per task) than to enforce labor services on reluctant serfs/ villeins (paid per day). The Medieval English economy The economy was overwhelmingly agricultural. Towns functioned as commercial centers, but long distance trade was still undeveloped. Medieval Europe had very poor roads: potholes could be large enough to overturn a cart. In wet weather, the roads became extremely muddy - not until the late 14th century were city streets cobbled with stones. Consequently, shipping by sea or river was far more efficient than land carting. Some developments in shipping did occur. In particular, the introduction of the cog - a transport ship that rode low in the water. Cogs were steered by a side oar and powered by a combination of oars and one yard sail. Its strong cross beams allowed for the transportation of greater quantities of cargo than earlier ships. These ships were short and stubby by modern standards, and the relatively large breadth to keel ratio made them difficult to maneuver. The introduction of the magnetic compass during the 12th Century considerably improved navigation. Although England's maritime trade grew during the 13th Century, international trade and commerce was dominated by the cities of Italy. Their commercial expertise and loan facilities enabled them to obtain special concessions from the English government. 4 England's main export was wool. During the later Middle Ages, England increasingly exported finished cloth, but raw wool was the primary export during the 13th Century. Cotswold lions, long haired sheep whose wool dominated English medieval output. English agricultural methods and productivity remained stagnant throughout the Middle Ages. The "strip" system of farming was equitable and extremely inefficient. Yields of grain per acre remained stagnant. Food production was only increased by bringing more land under the plow - a process that stopped once all available waste land had been improved. The introduction of the windmill (in place of the watermill) increased the efficiency of grinding grain for its operation continued even when the water was frozen or streams low. English population The population of Europe as a whole grew in the period 1000 to 1300. This coincided with the so-called "Medieval Warm Period," when the average temperature of Northern Europe was warmer than for 2000 preceding years, and far warmer than in the "Little Ice Age" that followed it. England's population increased from somewhere between 1.25 and 2.25 million at the time of the Norman Conquest, to at least 4 million (and possibly well over 6 or even 7 million) by 1300. The Growth in English population 5 Much of the growth in population took place in the North of England. This area recovered from the devastation inflicted by William I, helped by the warmer temperatures and a longer growing season. A number of new towns were founded - including Leeds (1207) and Liverpool (1229.) English medieval towns were very small by modern standards. Only London with a population of about 35,000 by 1300 was a large city. England's second city, Norwich grew from about 6,000 inhabitants in 1086 to about 10,000 in 1300. Population expansion and social conditions Because the number of people was growing while agricultural yields remained stagnant, people had to expand onto marginal land to increase food production. Forests were felled, marshes drained and arable crops planted in poor soil that had previously been used as pasture. Existing land was sowed more frequently and left fallow less often. These techniques expanded production initially, but yields tended to fall over time. The cutback in the area available for livestock decreased the volume of manure obtainable for fertilizing the soil. More people meant smaller acreage of land per person and this led to "harvest sensitivity." In years of poor harvests (such as the wet summers of 1315-1316) insufficient grain was grown and the poor starved. More people also meant more laborers and low wages. Landowners therefore had no reason to enforce servile labor. By 1300, slavery had died out and unfree tenures were becoming less common. (About one in two peasants was a villein in 1300, where two in three of those in Domesday Book were villeins.) However, there were still considerable variations in different areas of the country, and even within regions. In the North-west, for example, servile tenures predominated, while in Kent wealthy free peasants were the norm. 6 A medieval peasant's house. Wood was in short supply in medieval England so only the frame of the house was constructed of timber. There were no foundations, but the timbers were sometimes placed on stone supports to discourage damp and rot. The spaces in the walls were filled with branches and twigs, caked together with mud, and the whole surface was then coated with a limestone wash to render them waterproof. This system was called "wattle and daub." The roof was generally thatched with straw. The floor was simply earth, which was covered with straw (periodically thrown out and replaced) to reduce dust and dirt. The internal floor-plan tended to be very simple - the house was divided into a byre for livestock and supplies, and a living area for people with a central hearth. Generally, there was no chimney - smoke merely escaped through a hole in the roof. Increased population made peasants freer but poorer. By the late 13th Century, however, the evidence is clear that peasants preferred free tenure, even in areas where many free smallholders were very poor. Peasant uprisings from the mid 1200s almost always included demands for free status. High food prices and low wages made landowners richer, especially if they applied efficient management techniques. Accounting procedures grew more sophisticated, and new literature on agricultural improvement appeared. 7