Literature Review

advertisement

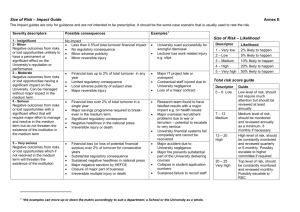

Running Head: ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER Organizational Commitment and Turnover: A Review of the Three-Component Model Daniel C. Hamm University of Central Florida 1 ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 2 Abstract A review of the literature on the relationship between organizational commitment and turnover was conducted. Specifically, the paper focuses on the three-component model of organizational commitment, which is comprised of affective, continuance, and normative commitment. Research on the topic showed varied results, however a basic negative correlation between the three components and turnover was established. Affective commitment was found to have the strongest correlation with turnover while continuance and normative commitments having mixed results. Other variables and the limitations on the three-component model were also addressed. ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 3 Organizational Commitment and Turnover: A Review of the Three-Component Model Employee turnover is one of the most costly problems that organizations face. The cost of a resigning employee is about equal to a year of their salaries (Boroş & Curşeu, 2013). Additionally, it takes time and money to select and train a replacement for a lost employee. Understanding the processes involved in employee turnover are important for increasing the effectiveness of organizations. In an attempt to combat this problem within organizations, an immense amount of research has been conducted on the antecedents of turnover in order to explain and predict these outcomes. From past research we can see that time and again, one of the most conclusive predictors of employee turnover and turnover intentions is organizational commitment. Organizational commitment is has been recognized as such, and yet many of the changes that organizations make still undermine employee commitment (Meyer & Parfyonova, 2010), and consequently, increasing turnover. More than ever it is important to understand the nature of commitment and its consequences. The purpose of this paper will be to review the literature on employee turnover, organizational commitment, and the relationship between these two constructs. Turnover Turnover is defined as the termination of one's employment with an organization (Tett & Meyer, 1993). Turnover is usually considered to be a voluntary act, which is important to note, as many of the models of turnover apply specifically to self-motivated termination. When understanding turnover, it is also important to consider its antecedents. Sometimes commitment will have a strong correlation with one of the precursors of turnover. Findings from turnover ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 4 research have consistently found turnover intention to be the strongest cognitive precursor of employee turnover (Tett & Meyer, 1993). Turnover intention is defined as a "conscious and deliberate willfulness to leave the organization" (Tett & Meyer, 1993 p.262). However, needless to say, not all employee who show turnover intentions will act upon these intentions and leave their organization. Many of the employee turnover models that have been developed over the years show turnover intentions (or intent to quit) as a logical precursor to employee turnover. (Mobley, 1977; Dalessio, Silverman, & Schuck, 1986; Hom, Griffeth, & Sellaro, 1984). For example, the Steers and Mowday (1981) model of employee turnover shows a sequence of intention to leave an organization followed by turnover. This model shows that intention to leave may differ from each individual. Sometimes intention to leave will directly relate to employee turnover. Other times, however, intention to leave will lead an individual to start searching for other job opportunities (Lee & Mowday, 1987). Figure 1. Antecedents of Turnover Intentions. Adapted from “Is it here where I belong? An integrative model of turnover intentions,” by Boroş, S., & Curşeu, P., 2013, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43, p.1555. ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 5 Turnover intentions are typically considered part of a broader set of withdrawal cognitions. Withdrawal cognitions incorporate a number of cognitive thoughts that an employee engages in. Intention to quit is actually the last in the sequence, before employees actually decide to leave their organization. Withdrawal cognitions also include thinking of quitting and intention to search (for new opportunities) (Tett & Meyer, 1993). In some studies, as seen later in this paper, the relationship between organizational commitment and withdrawal cognitions are correlated. This relationship is specifically important, as organizations are increasingly interested in preventing turnover. Learning how organizational commitment is linked to the precursors of turnover may provide some support in solving this problem. Organizational Commitment and the Three-Component Model Over the past few decades organizational commitment has been defined and measured in many ways (Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001). Mowday and colleagues (1979) describe it as "the relative strength of an individual's identification with and involvement in a particular organization" (p.226). It has also been simply defined as "a bond or linking of an individual to the organization (Mathieu & Zajac, 1990, p.171). While many of these definitions look at organizational commitment as a one-dimensional construct, Meyer and Allen (1991) developed a multi-dimensional model of commitment that is still one of the most referenced and relied on models today (Culpepper, 2011). Their three-component model of organizational commitment is separated into what they argue are the three different rationalities behind commitment. These are affective, continuance, and normative commitment. Essentially, this model is defined in the terms of employee retention (Culpepper, 2011). Broadly defined, the model states that individuals remain with their organization because they either want to (affective commitment), need to (continuance commitment), or feel obligated to (normative commitment) (Meyer, Allen, ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 6 & Smith, 1993). Meyer and Allen (1991) argue that organizational commitment is best understood when we look at all three forms of commitment, as an individual can have varying levels of each. More specifically, affective commitment refers to how much an individual is involved, or enjoys membership in an organization. It can also be described as an emotional attachment to an organization (Meyer & Allen, 1990). This is the most typical kind of organizational commitment and previously thought to be the only type of commitment. Continuance commitment refers to the individual's perception of the costs and loss of benefits that are associated with leaving the organization. An employee may believe that there are no other opportunities comparable to their current position available outside of their organization. Even if an employee wants to leave their organization for various other reasons, they may feel that they have too many investments that they would risk losing if they were to walk away (Meyer, Allen, & Smith, 1993). This type of commitment also includes social and economic costs of leaving (i.e. relocation costs and disrupted social networks) and transferability of skills (Sinclair, van Olffen, & Roe, 2005). Another term appropriately used to describe this component is side bet commitment. After the first two components were established, Allen and Meyer (1990) suggested a third component, normative commitment, was important to understanding the reasoning behind organizational commitment. Normative commitment refers to an internalized obligation to remain with an organization (Meyer Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, 2002). Employees who are experiencing normative commitment would likely state that they will continue to stay with their organization because it is the right thing to do (Meyer & Allen, 1991). Herscovitch and Meyer (2002) have added that normative commitment can include a sense of obligation to provide support for change in an organization. ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 7 Three-Component Model and Employee Turnover Commitment-turnover relationships have generally been conceptualized within the 'attitude-intention-behavior' approach (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). Commitment theory has suggested that the strength of an individual's ties with the organization determines how strongly they will leave the organization (Tett & Meyer, 1993). Commitment may shape the cognitive appraisal of one's organizational membership or the perspective of leaving. Appraisal is an evaluation of what one's relationship to the environment implies for personal well-being. Commitment mindsets shape the cognitive framework which individuals assess whether the perspective of leaving or staying in an organization represents a threat to their well-being (Vandenberghe, Panaccio, & Ayed, 2011). We will now review how the three-component model relates to turnover. Figure 2. Three-Component Model of Commitment. Adapted from “Affective, Continuance, and Normative Commitment to the Organization: A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents, Correlates, and Consequences,” by Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., and Topolnytsky, L, 2002, Journal of Vocational, 61, p. 22. ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 8 Affective Commitment and Turnover Numerous studies have found that affect commitment typically shows the highest correlations with employee turnover and turnover intentions than any other component. Therefore most of the research tends to focus on affective commitment because of its ability to predict organizationally important outcomes (Allen et al., 2003). This relationship is likely due to the attitudes associated with affective commitment. Rather that feeling obligated or needing to stay with an organization, someone with strong affective commitment has a desire to stay as opposed to the perceived costs or obligations (Vandenberghe & Bentein, 2009). In a metaanalysis conducted by Meyer et al. (2002), affective commitment had the highest effect sizes for both turnover (ρ= -.17) and withdrawal cognition (ρ= -.56). Mohammed, Taylor, and Hassan (2006) conducted an experiment to test the relationship of affective commitment and intention to quit for correctional officers. Their findings showed a significant, strong negative correlation between the two variables (r= -.627). While this is not a correlation with actual turnover, it is important to establish the relationship that different components of organizational commit have with several antecedents to turnover. As stated previously, the intention to quit is one of the most significantly significant antecedents to actual employee turnover. Past research has mainly focused on employee's commitment to the global organization. Vandenberghe and colleagues (2004), conducted a number of interesting studies that investigates how affective commitment to different foci (the organization, supervisor, and work-group) relates to employee turnover. They argue that organizational commitment involves a number of different commitments that are not independent of each other. Their theory is based off the ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 9 findings of Herscovitch and Meyer (2002), who found that when commitment was directed at a specific foci, it was a better predictor of behavior than a more general conceptualization of organizational commitment. Vandenberghe and colleagues (2004) found that affective organizational commitment had a significant indirect effect on employee turnover through intention to quit. Their studies also showed that affective commitment to the supervisor and to the work group have a significant indirect effect on turnover through affective organizational commitment. Continuance Commitment and Turnover Continuance commitment is typically regarded differently than affect and normative commitment. Continuance commitment is considered a cognitive attitude, such as weighing the financial and social pros and cons of staying in an organization (Culpepper, 2011). This is different from affective and normative commitment which are typically regarded as emotionbased, such as a feeling of desire or obligation to stay. Continuance commitment has often shown to have a weak or inconsistent relationship with intended and actually turnover (Meyer et al. 2002). Possibly due to these inconsistent findings, much of the research has chosen to only look at affective commitment and leave out continuance commitment. In Meyer and colleague's (2002) meta-analysis, continuance commitment showed the weakest effect sizes of the threecomponents. For turnover, the findings were ρ= -.10, and for withdrawal cognitions, ρ= -.18. Since the original model was proposed, it has been suggested that continuance commitment can actually be broken down into two separate categories: high-sacrifice commitment and low-alternatives commitment. High-sacrifice commitment refers to the perceived sacrifice of leaving an organization and low-alternatives commitment refers to the ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 10 costs of a lack of employment opportunities (Vandenberghe, Vandenberg, & Stinglhamber, 2005). These two subcategories correlate positively with each other but have shown to have relationships with work-related variables that are significantly different from each other (Vandenberghe, Panaccio, & Ayed, 2011). The distinction between these is important to note as shown in the meta-analysis by Meyer et al. (2002). When continuance commitment was separated between these two subcomponents, two very different results were found. Highsacrifice commitment was to be significantly correlated with withdrawal cognitions (ρ= -.21) while the low-alternatives commitment did not (ρ= -.01). A study by Vandenberghe, Panaccio, and Ayer (2011) took it a step further by examining the moderating role of negative affectivity and risk aversion in relationship of the continuance subcategories and turnover. Their results found that negative affectivity and risk aversion strengthens the negatively relationship between high-sacrifice and low-alternatives commitment. They argue that the perception of leaving an organization (high-sacrifice commitment) and moving to another organization (low-alternatives commitment) are stressful. An individual's appraisal of available resources to face the stressful situation, which determines whether they will commit turnover, is influenced by their level of negative affectivity and risk aversion. Normative Commitment and Turnover Out of three components of commitment, normative commitment seems to receive the least attention. Although it is theoretically different from affective commitment, many of the antecedents and consequences are shared between the two and there is a high correlation between the two constructs, making it difficult to distinguish between them (Meyer & Parfyonova, 2010). ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 11 In the meta-analysis by Meyer et al. (2002), normative commitment showed the second highest effect sizes with employee turnover and withdrawal cognition (ρ= -.16 and ρ= -.33 respectively). Valéau and colleagues (2013) conducted a study which investigated the relationship of the three-component model of commitment and turnover intentions in relation to volunteers. Interestingly, they found that normative commitment, at least in this context, was the only significant predictor of turnover intentions. This however, this could be unique to volunteers who might have an increased sense of obligation to work for an organization. They might see volunteering for an organization as the right thing to do (Valéau et al., 2013). Temporal Aspects of the Three-Component Model and Turnover While many studies have viewed organizational commitment as a sole predictor of turnover, some studies have found other variables might have an effect on this relationship. A study by Culpepper (2011) employees of a home improvement retailer were surveyed to see how temporal aspects relate to the three-component model of commitment and turnover. The author states that the role of time has been neglected in past research and could be an important mediator on the commitment-turnover relationship. Typically, research in this area has shown to give affect continuance commitment the most. Continuance commitment has been shown to correlate more highly with future turnover (r= -.25) than contemporaneous intent to leave (-.22) (Mathieu &Zajac, 1990). In Culpepper's (2011) study, turnover rates grew over time for participants with low side-bet (continuance) commitment. However, continuance commitment was not significantly correlated in on a shortterm basis. This gives evidence to the theory that continuance commitment is stable over time, unlike affective and normative commitments (Meyer et al., 1993). Culpepper (2011) argues that ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 12 research measuring the continuance commitment-turnover relationship with less than a 6 month time frame may fail to fully capture accurate results. This may explain the lack of a strong correlation in Meyer et al.'s (2002) meta-analysis. Unlike continuance commitment, the results of Culpepper's (2011) study showed that affective commitment was a better predictor of turnover in the short term. Affective commitment was more highly correlated in the first four months of the study (r= -.34), than in the 5-12 month period afterward (r= .06). This supports that the author's notion that low affective commitment reflects an intention to leave the organization that is inherent. Furthermore, Culpepper (2011) argues that when affective commitment in measured over longer durations, we will see lower correlations with turnover and risk losing information about the true relationship. When comparing short-term and long-term differences in commitment-turnover relationships, it seems that normative commitment does not add much information in the prediction of turnover. Results from Culpepper's (2011) study showed a higher correlation (r= .17) in early months than in later months (r =.05), however neither of these statistics were significant. We see that the results added little information after accounting for the information already afforded by affective commitment. This may be a consequence of a conceptual problem that will be further discussed in the next section. Limitations of the Three-Component Model As we have previously established, the three-component model is the dominant conceptualization of organizational commitment. Despite the numerous contributions to the field that have relied on this model, many research argue that there many limitations that we must ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 13 address. Solinger, van Olffen, and Roe (2008) outline many of these limitations. In their paper they argue that studies have found poor or slightly negative correlations between continuance and affective commitment. For example, Meyer et al. (2002) found a correlation coefficient of only .05 in an analysis of 92 studies. This research suggests that there might be an issue in the convergent validity of continuance commitment. As discussed previously and in the analysis by Solinger et al. (2008), another possible limitation of the model is the very strong correlation between affective and normative commitment. In an analysis of 54 studies, a correlation of r=.63 was observed between the two components (Meyer et al., 2002). Many believe that it is difficult to empirically measure the two constructs separately, while others believe that the problem is a conceptual one and that affective and normative commitment are too similar, possibly measuring the same construct (Solinger et al., 2008). To resolve these issues, Ko, Price, & Mueller (2007) proposed that we should return to looking at organizational commitment as a one dimensional construct. They argue that affective commitment has the highest correlation to performance, organizational citizenship behaviors, and turnover. Affective commitment also has the greatest content and face validity, making it the most reliable dimension of organizational commitment (Allen & Meyer, 1996; Meyer et al. 2002). By eliminating continuance and normative commitment from the model, we may have a better conceptualization of organizational commitment and therefore able to make better predictions of its consequences. ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 14 Discussion As we can see, organizational turnover is an on-going problem. However, the literature focusing on organizational commitment and turnover has come a long way to provide us with an understanding into the relationship of these constructs. The three-component model has provided researchers with a way to conceptualize the multi-dimensionality of organizational commitment. Overall, a negative correlation between organizational commitment and turnover is shown in most studies. We can conclude that, generally, the more an individual is committed to his or her organization, (by affective, continuance, or normative means) the less likely they are to leave that organization. Affective commitment has been the most promising aspect of organizational commitment and turnover research. It has shown the greatest correlations with turnover and turnover intentions. The relationship between affective commitment and turnover intentions is not a surprising one. When organizations provide the kinds of support needed and desired by employees, a reciprocal obligation often develops in which the employee feels obliged to return this support, and one way of doing this is staying with the organization (Mohamed et al., 2006). Affective commitment is also viewed as the most valid of the three components. Confusion and controversy within the academic community typically surrounds research on continuance and normative commitment, but affective commitment is widely accepted as a sound construct. There may be many positive outcomes for organizations that focus on achieving high affective commitment with their employees. For continuance commitment, since it typically shows a weak relationship with turnover, the inclusion of moderating variables has been a promising new focus for this component. The distinction among high-sacrifice and low-alternatives commitment, may provide clarity on how continuance commitment influences employee ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 15 turnover. Despite the problems addressed regarding normative commitment, it might be beneficial for future research to be conducted on this component of commitment. If researchers could better differentiate normative and affective commitment, possibly through new measures, we may be able to have more convincing results. Withdrawal cognitions seem to correlate higher with organizational commitment than turnover. This is not surprising due to the logical progression of withdrawal cognition to turnover. As an antecedent of turnover, withdrawal cognitions are usually shown before turnover occurs. Yet not everyone who shows withdrawal cognitions will ultimately decide to leave their organization. Therefore, the amount of employees who lack organizational commitment and show withdrawal cognitions will likely be higher than those lack commitment and eventually leave. Some researchers are creating promising new theories on the commitment-turnover relationship. Studies on the temporal aspects of commitment and turnover are an example of this promising new research. Culpepper's (2011) study has shown that time is a factor that I/O psychologist must consider when looking at commitment. Affective and continuance commitment specifically, have substantially different predictors of turnover when comparing short and long term differences. Additionally when separated in this fashion, correlations with turnover are show to be stronger. Further research on this variable as well as other on the relationship of commitment and turnover would be the next logical step in this area of study. However, as we have seen from the literature, the three-component model has its flaws and limitations. Certain types of commitment have been studied more than others, and findings from each have not been consistent across studies. This is likely due to issues in convergent ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 16 validity within continuance commitment, as well as many arguing that affective and normative commitment are too alike. Despite these issues, the three-component model may be the best conceptualization of organizational commitment and the benefits of using it will likely outweigh the possible flaws. Overall, the findings from the research on the three-component model of organizational commitment and turnover have been promising. Organizations would be wise to take this information for implementation. Making an effort to keep employees committed to their organization through affective, continuance, and normative means will likely reduce future turnover and withdrawal cognitions. Given the difficulty of finding skilled and competent employees in today's environment, employee retention is extremely important. ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 17 References Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J.P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63, 1-18 Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1996). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: An examination of construct validity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 49(3), 252-276. Bentein, K., Vandenberghe, C., Vandenberg, R., & Stinglhamber, F. (2005). The Role of Change in the Relationship Between Commitment and Turnover: A Latent Growth Modeling Approach. Journal Of Applied Psychology, 90(3), 468-482. Boroş, S., & Curşeu, P. (2013). Is it here where I belong? An integrative model of turnover intentions. Journal Of Applied Social Psychology, 43(8), 1553-1562. Culpepper, R. A. (2011). Three-component commitment and turnover: An examination of temporal aspects. Journal Of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 517-527. Dalessio, A., Silverman, W. H., & Schuck, J.R. (1986). Paths to turnover: A re-analysis and review of existing data on the Mobley, Horner, and Holligsworth turnover model. Human Relations, 39, 245-264. Eagly, A.H., Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Orlando, FL: Harcourt. Herscovitch, L., & Meyer, J. P. (2002). Commitment to organizational change: Extension of a three-component model. Journal Of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 474-487. ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 18 Hom, P. W., Griffeth, R. W., & Sellaro, C.L. (1984). The validity of Mobley's (1977) model of employee turnover. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 34, 141-174. Ko, J., Price, J. L., & Mueller, C. W. (1997). Assessment of Meyer and Allen's three-component model of organizational commitment in South Korea. Journal Of Applied Psychology, 82(6), 961-973. Lee, T. W., & Mowday, R. T. (1987). Voluntarily leaving an organization: an empirical investigation of Steers and Mowday's model of turnover. Academy Of Management Journal, 30(4), 721-743. Mathieu, J.E., & Zajac, D., (1990). A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 171-194. Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J., (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1, 61-89. Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal Of Applied Psychology, 78(4), 538-551. Meyer, J.P., Herscovitch L., (2001). Commitment in the workplace: toward a general model. Human Resource Management Review, 11(3), 299-326. Meyer, J. P., & Parfyonova, N. M. (2010). Normative commitment in the workplace: A theoretical analysis and re-conceptualization. Human Resource Management Review, 20(4), 283-294. ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 19 Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal Of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20-52. Mohamed, F., Taylor, G., & Hassan, A. (2006). Affective Commitment and Intent to Quit: The Impact of Work and Non-work Related Issues. Journal Of Managerial Issues, 18(4), 512529. Molbey, W. H. (1977). Intermediate linkages in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62, 237-240. Mowday, R.T., Steers, R., & Porter, L. W. (1979). The measure of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 14, 224-247. Sinclair, R. R., Tucker, J. S., Cullen, J. C., & Wright, C. (2005). Performance Differences Among Four Organizational Commitment Profiles. Journal Of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1280-1287. Solinger, O. N., van Olffen, W., & Roe, R. A. (2008). Beyond the three-component model of organizational commitment. Journal Of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 70-83. Steers, R. M., & Mowday, R. T. (1981). Employee turnover and post-decision accommodation processes. Research In Organizational Behavior, 3, 235-281. Tett, R. P., & Meyer, J. P. (1993). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Personnel Psychology, 46(2), 259-293. ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND TURNOVER 20 Valéau, P., Mignonac, K., Vandenberghe, C., & Gatignon Turnau, A. (2013). A study of the relationships between volunteers' commitments to organizations and beneficiaries and turnover intentions. Canadian Journal Of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement, 45(2), 85-95. Vandenberghe, C., & Bentein, K. (2009). A closer look at the relationship between affective commitment to supervisors and organizations and turnover. Journal Of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 82(2), 331-348. Vandenberghe, C., Bentein, K., & Stinglhamber, F. (2004). Affective commitment to the organization, supervisor, and work group: Antecedents and outcomes. Journal Of Vocational Behavior, 64(1), 47-71. Vandenberghe, C., Panaccio, A., & Ayed, A. (2011). Continuance commitment and turnover: Examining the moderating role of negative affectivity and risk aversion. Journal Of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(2), 403-424.