Recount Writing for Junior Students

advertisement

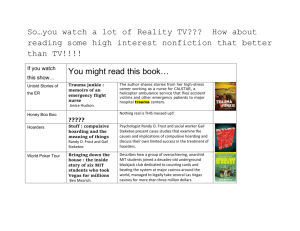

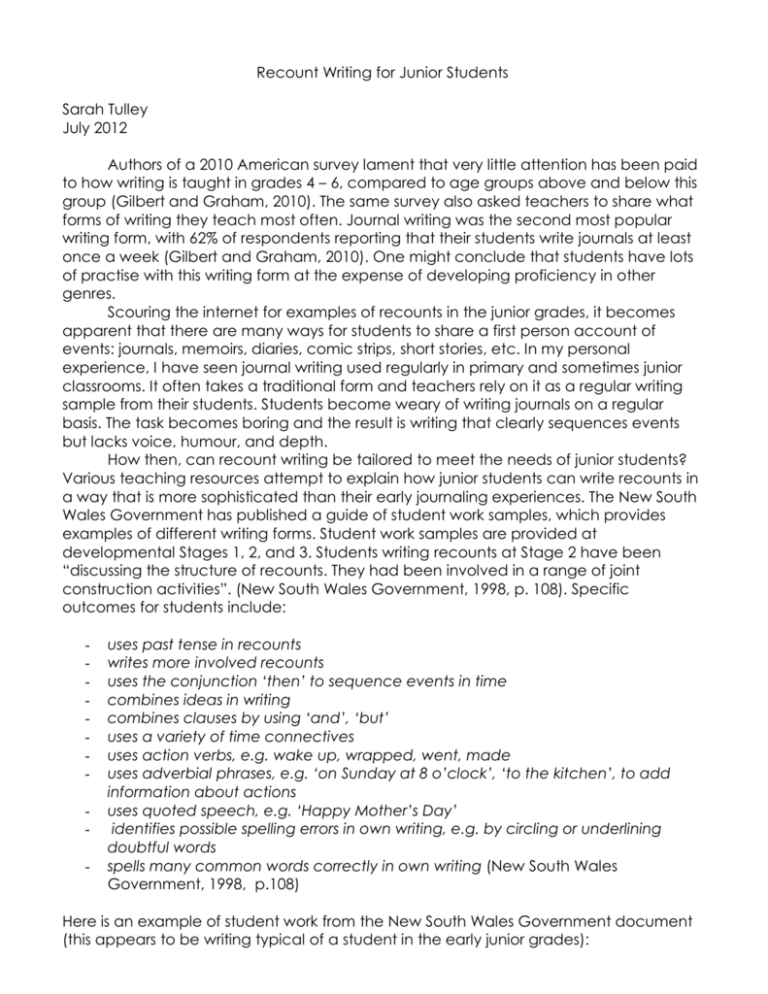

Recount Writing for Junior Students Sarah Tulley July 2012 Authors of a 2010 American survey lament that very little attention has been paid to how writing is taught in grades 4 – 6, compared to age groups above and below this group (Gilbert and Graham, 2010). The same survey also asked teachers to share what forms of writing they teach most often. Journal writing was the second most popular writing form, with 62% of respondents reporting that their students write journals at least once a week (Gilbert and Graham, 2010). One might conclude that students have lots of practise with this writing form at the expense of developing proficiency in other genres. Scouring the internet for examples of recounts in the junior grades, it becomes apparent that there are many ways for students to share a first person account of events: journals, memoirs, diaries, comic strips, short stories, etc. In my personal experience, I have seen journal writing used regularly in primary and sometimes junior classrooms. It often takes a traditional form and teachers rely on it as a regular writing sample from their students. Students become weary of writing journals on a regular basis. The task becomes boring and the result is writing that clearly sequences events but lacks voice, humour, and depth. How then, can recount writing be tailored to meet the needs of junior students? Various teaching resources attempt to explain how junior students can write recounts in a way that is more sophisticated than their early journaling experiences. The New South Wales Government has published a guide of student work samples, which provides examples of different writing forms. Student work samples are provided at developmental Stages 1, 2, and 3. Students writing recounts at Stage 2 have been “discussing the structure of recounts. They had been involved in a range of joint construction activities”. (New South Wales Government, 1998, p. 108). Specific outcomes for students include: - uses past tense in recounts writes more involved recounts uses the conjunction ‘then’ to sequence events in time combines ideas in writing combines clauses by using ‘and’, ‘but’ uses a variety of time connectives uses action verbs, e.g. wake up, wrapped, went, made uses adverbial phrases, e.g. ‘on Sunday at 8 o’clock’, ‘to the kitchen’, to add information about actions uses quoted speech, e.g. ‘Happy Mother’s Day’ identifies possible spelling errors in own writing, e.g. by circling or underlining doubtful words spells many common words correctly in own writing (New South Wales Government, 1998, p.108) Here is an example of student work from the New South Wales Government document (this appears to be writing typical of a student in the early junior grades): (1998, p. 108) The Ontario Literacy and Numeracy Secretariat (LNS) has created a resource that outlines the important features of non-fiction writing for junior students. This resource names the following goals for students writing recounts: - recounts are usually written in the first person, in the past tense, and in chronological order. The writer uses “doing” or action clauses. “scene setting” (opening/orientation) – “I went to the symphony with my class.” retelling of the events as they occurred – “I studied every move that the conductor made.” closing statement (reorientation) – “When we got back from the trip, I conducted my friends singing ‘Yellow Submarine’ in 4/4, 2/4 and 3/4 time, using the same moves.” (2008, p. 4) Various resources, including the LNS resource, describe different organizational patterns that junior students should be aware of when reading and writing non-fiction texts. They include chronological order, concept/definition, description, episode, generalization/principle, process/cause and effect (1998, p. 6). One or more of these patterns can exist in different text forms. They should be modeled and explored with students (1998, p. 6). Some educators argue that children find writing non-fiction more challenging than fiction due the prescribed text structures (Wray, 2001). To support students, authors like Wray have suggested the use of writing frames (2001). This is a skeletal framework to assist in the pre-writing stage, so that students don’t “wander” between different writing forms (Wray, 2001, p. 3) An internet search for recount writing frames reveals a number of graphic organizers prompting students to include basic elements such as the 5 Ws and beginning, middle, and end. Because many students have been writing recounts in the form of journals since a young age, I think it is important to model and encourage different forms of expression in the junior grades. Recounts can be shared in a diary, a comic strip, a pod cast, a dramatic reenactment, a comedy sketch, or a flow chart. On the other hand, the fact that many junior students are familiar with this writing form can be taken as an opportunity for students to enhance their craft as writers. When they write recounts, students can be exposed to and practice using humour, dialogue, metaphor, complex sentence structure, or word choice. References: Gilbert, J. and Graham, S. (2010). Teaching Writing to Elementary Students in Grades 4 6: A National Survey. The Elementary School Journal, 110 (4), 494 – 518. Literacy and Numeracy Secretariat. (2008). Non-fiction Writing for the Junior Student (Secretariat Special Edition #5). Available online: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/literacynumeracy/inspire/research/Non_Fiction_ Writing.pdf New South Wales Government. (2008). Student Work Samples: Writing. (K – 6 Educational Resources: English Syllabus). Available online: http://k6.boardofstudies.nsw.edu.au/files/english/write_k6engsamples_syl.pdf Wray, D. (2001). Developing Factual Writing: An Approach Through Scaffolding. Paper delivered at European Reading Conference. Dublin, Ireland.