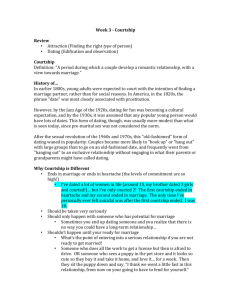

5 Courtship and Mate Selection

Student Resources: Guiding Questions, Chapter Outline, Website & Article Resources

Guiding Questions

After reading the chapter, the student should be able to answer the following questions:

Is courtship a stage in the family life cycle?

What factors (individual, couples, and contextual) affect whether two people are

drawn together into a union?

How do new cultural phenomena such as the internet and long distance dating

affect relationships?

How do some of the prominent models of mate selection (stage models,

interpersonal process models, ecological models, evolutionary models) suggest that

people select mates?

Is cohabitation on the rise, and are couples who cohabit prior to marriage different

from couples who do not?

Chapter Outline

1. Factors That Influence Courtship and Mate Selection

a. Individual Factors: Personal Attributes and Characteristics

i. Age

ii. Self Beliefs and Relationship Beliefs

iii. Past relationship Experiences

b. Individual Factors: Personal Mate Preferences

i. Chastity

ii. Physical Attractiveness

iii. Financial Resources, Cooking/Housekeeping, and Mutual Attraction/Love

iv. Limitations to Research on Mate Preferences

c. Couple Factors: Partner Compatibility

i. Assortive Matching for Sociocultural Variables: Age, Race, Education,

Socioeconomic Class, and Physical Attractiveness

ii. Assortive Matching for Psychosocial Variables: Role and Leisure

Preferences, Communication Values, and Psychological Qualities

iii. Does Similarity Really Breed Attraction?

d. Couple Factors: Partner Interaction

© Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011

i. Initiating and Experimenting Stages: Flirting, Dating, and Reducing

Uncertainty

ii. Intensifying and Integrating Stages: Expressing Commitment and Dealing

with conflict

iii. Bonding Stage: Decisions to Formalize the Union

e. Contextual Factors

i. Socio-cultural Networks

ii. Environmental Contexts: Proximity

iii. Environmental Contexts: Long-Distance Dating

iv. Environmental Contexts: Online Dating

2. Models of Mate Selection

a. Stage Models

i. Winch's Complementary Needs Model

ii. Murstein's Stimulus–Value–Role Model

b. Interpersonal Process Models

c. Ecological Models

d. Evolutionary Models

3. Cohabitation

d. Are People Who Cohabit Different?

e. Does Cohabitation Change People?

2. Conclusion

Website and Article Resources

TV Reality Show and Game Show Portrayals of Dating and Courtship

Since their inception, television, films, magazines, novels, pop music, and many other media

genres have portrayed courtship and mate selection processes. Sometimes these portrayals are

very realistic. However in many instances, they are trivialized, sexualized, oversimplified, and

stereotyped in order to offer audiences tantalizing, humorous, satirical, or short-term glimpses

of dating life. In the last half-century, TV game shows and reality shows have developed an

appetite for dating, courtship, and interpersonal attraction. Hetsroni (2000) observes that there

have been two types of courtship games on television. The first type involves shows such as the

1960s/1970s Newlywed Game, where husbands and wives were separately asked the same

questions about each other and their relationship. Couples who had the most answers in

common won a prize, under the assumption that they had a courtship process that helped

them get to know each other better than the other couples. The second type, of more recent

interest, involves a male or female who selects a mate among numerous candidates and rounds

of elimination. This second type of show was popularized by The Love Connection in the 1980s

and generated more interest in the 1990s and early 2000s, with MTV’s Singled Out and other

major network productions such as Who Wants to Marry a Millionaire, Blind Date, The

© Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011

Bachelor, The Bachelorette, and numerous other shows with related premises such as Change

of Heart or Temptation Island.

It’s obvious why the networks like such shows: they are typically inexpensive and good at least

for short-term ratings. Why do audiences like them so much? Such shows are a mix of sport,

fairytale, and comedy. Avins (2002), for example, argues that people are “voyeurs” who “find

sport in the brutality of modern courtship” (p. F1). Similarly, Farhi (2002) interviewed numerous

people who admitted that the shows were “cheap and tacky,” but that they were seduced by

the fairytale image of people trying to find the “perfect” match (p. C1). Further, people get a

chance to laugh at themselves and see some of the crazy things they may actually do in the

dating process. Is there any harm in these TV dating game shows? Hetsroni (2000) feels that

dating game participants place far more emphasis on physical characteristics and sex-related

qualities of potential mates rather than lifestyle, psychological, and communication qualities.

Perhaps participants can afford to look primarily at superficial qualities knowing that they may

not necessarily be with these partners for the long term. Besides, Roug and Lowry (2002) argue

that most audiences understand that TV dating game shows are just comedies and that most

people watch with the notion that they would never act like most of the contestants.

Ward (2002) presents an alternative perspective. At least with regard to TV (e.g., soap operas),

films, and music videos, Ward feels that media portrayals of courtship for the most part

negatively influence young people’s notions of what constitutes proper and common dating

behavior. Ward’s correlational and experimental data show that young adults who consume a

lot of television are more likely to endorse attitudes indicating that sexual relationships are

recreationally oriented, that pregnancy and STDs are not major risks in casual sex, that most of

their peers are “doing it,” and that sexual stereotypes (e.g., men are sex driven and women are

sex objects) hold true. As Ward says, we need more research to address whether endorsement

of such attitudes actually leads to risky behaviors. What do you think?

Avins, M. (2002, April 27). Charmed silly: What made ‘The Bachelor’ such a guilty pleasure? For

the series’ exhibitionist contestants and voyeuristic viewers, it was a match. The Los

Angeles Times, pp. F1.

Farhi, P. (2002, November 20). Popping the question: Why has ‘The Bachelor’ become

irresistible to women? Stay tuned. The Washington Post, pp. C1.

Hetsroni, A. (2000). Choosing a mate in television dating games: The influence of setting,

culture, and gender. Sex Roles, 42, 83106.

© Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011

Roug, L., & Lowry, B. (2002, August 18). Dating fame games: A rash of new shows stresses the

comedy in courtship humiliation. Why do we watch this stuff? The Los Angeles Times,

pp. F10.

Ward, L.M. (2002). Does television exposure affect emerging adults’ attitudes and assumptions

about sexual relationships? Correlational and experimental confirmation. Journal of

Youth and Adolescence, 31, 115.

For further reading on reality dating show portrayals’ of dating and courtship see:

Ferris, A.L., Smith, S.W., Greenberg, B.S., & Smith, S.L. (2007). The content of reality dating shows and

viewer perceptions of dating. Journal of Communication, 57(3), 490510.

© Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011