Research Study - Shannon Deets Counseling

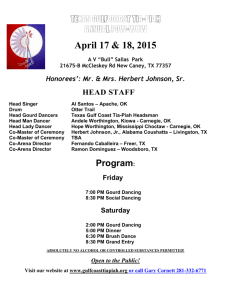

advertisement