code switching - WordPress.com

advertisement

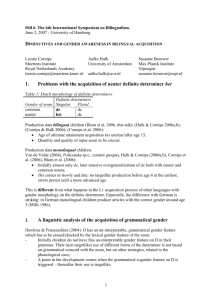

Anhar Teo Sandrea 2201410108 Topic Applied Lingustics Rombel 205-206 Why do People Code-swith? People who switch back and forth from one language to the other are considered careless, thoughtless, clumsy, not interested or disrespectful towards their languages. However, a lot of interesting observations can be made from this! Linguists who study code-switching may ask two types of questions which I will return to below. The first question is: WHY do people switch? And that has everything to do with identities, proficiency, situation, speech partners, etc. The second question is: HOW do people switch? And that is a more grammatical topic. WHY do people code-switch? Have you ever heard an official speech in which code-switching occurred? Probably a single word every now and then, but not more than that. Obviously, when we try to speak with great care, when we want to make a well-prepared and educated impression, we do our best to stick to one language. But usually, in our day-to-day contacts, we are not very careful and we don’t pay special attention to how we say things, as long as our message is clear. People who switch a lot between their languages in bilingual encounters will not do so with speech partners who understand only one of their languages. It does not make sense to use, say, Turkish with a speech partner who does not speak or understand a word of Turkish. Some linguists have stated that ‘true’ code-switching is only possible when a speaker is fully proficient in two (or more) languages, or a ‘balanced bilingual.’ But how many people are equally native-like proficient in two or more languages? Not many, I would guess. But that does not mean that they are unable to switch between languages! Sometimes people switch when they don’t know a word in one language. Most multilinguals have a ‘better’ language, but it all depends on the topic and speech partners. Sometimes people switch because they want to show their speech partners that they also know the other language, or because it ‘sounds better’ in the other language. A Turkish/Dutch girl I know told me that she curses in Dutch and not in Turkish because in Turkish it would sound more serious, more severe. When a Dutch-Arabic bilingual living in the Netherlands wants to talk about Islam, (s)he will prefer Arabic, but when (s)he talks about school, Dutch is preferred. The same person might feel uncomfortable speaking Dutch to his or her parents and Arabic to friends. When I talk with an Arab in the Netherlands, we might both use Dutch and I might sometimes use some Arabic words in order to identify myself as a person who knows some Arabic, even though my Arabic is very poor. Code-switching identification is a powerful tool for identification. HOW do people code-switch? Codeswitching within sentences is not something people do whenever they feel like it! Whenever switching takes place within a sentence, there are strict grammatical rules to be obeyed. Nobody told the bilinguals what these rules are, there is no book or grammar that prescribes when and how to switch, and yet bilinguals know these rules! People who switch within a sentence have to know the grammar of both languages. In English, for example, the verb comes right after the subject. In Turkish, but also in Dutch and German subordinate sentences, the verb is the last word of the sentence. So when you want to switch from English to German in a subordinate sentence, and you already used the verb in English (and you don’t want to violate either grammars), you have a problem, as in this example: (1) (…) because he wanted to buy books yesterday (2) (…) weil er gestern (…) ‘because he yesterday books buy wanted’ Bücher kaufen wollte (German) I leave it to the German-English readers to come up with a solution. Where would you switch from one language to the other in the sentence above without making grammatical errors? Even when there are no word order difficulties such as those listed above, you still can only switch at certain points, not randomly. For example, switching after every second word as in examples (5) and (6) below leads to impossible sentences. (Sentences (3) and (4) below are the monolingual equivalents.) (3) I bought (4) Ik kocht het laatste exemplaar (Dutch) the last copy (English) (5) (6) Ik bought het last exemplaar I kocht the laatste copy Sentence (5) and (6) are simply wrong. Bilinguals just would not say something like that. However, the next two sentences sound much more acceptable: (7) Ik (8) I bought het laatste exemplaar kocht the last copy People who never learned what a ‘subject pronoun’ or a ‘finite verb’ is, know exactly that switching between a subject pronoun and a finite verb, as in (5) and (6), is unacceptable in bilingual speech. Isn’t that amazing? They also know that code-switching between finite verb and direct object is less problematic, as in (7) and (8). These examples were from English, Dutch and German. However, the rules like the ones above apply to all possible language pairs which means that all bilinguals, whatever their languages, know these rules. And not only between spoken languages but also between spoken and signed languages. Deaf people are also able to switch between sign language and a spoken language, and they do so when they are communicating with other bilingual speaking/signing people.