Securing SER workshop report 31 Aug to 2 Sep 09 draft

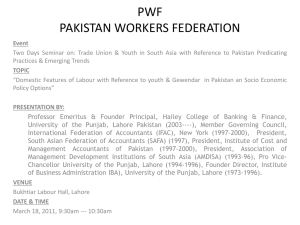

advertisement