electron spin & magnetism

advertisement

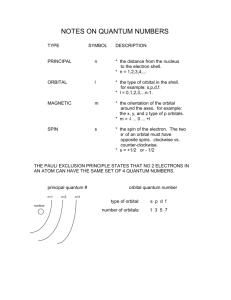

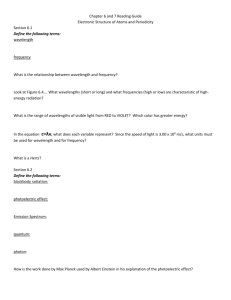

Chapter 8 Electron Configuration and Chemical Periodicity Factors Affecting Atomic Orbital Energies: The Effect of Nuclear Charge (Zeffective) Higher nuclear charge lowers orbital energy (stabilizes the system) by increasing nucleus-electron attractions. The Effect of Electron Repulsions (Shielding) Additional electron in the same orbital An additional electron raises the orbital energy through electron-electron repulsions. Additional electrons in inner orbitals Inner electrons shield outer electrons more effectively than do electrons in the same sublevel. ELECTRON SPIN & MAGNETISM Electron Spin: you need to understand magnetism & ionization energy to understand electron spin and quantum number ms. Magnetism and what you already know: earth has a magnetic field, with a North Pole and South Pole, as do metal magnets Electromagnetism = magnetic field created by electrical current Three definitions for magnetic substances: paramagnetic = attracted to magnetic field diamagnetic = not attracted to magnetic field ferromagnetic = substance that retains its magnetism after being placed in magnetic field (like Fe, Co & Ni) Figure 8.19 Apparatus for measuring the magnetic behavior of a sample ELECTRON SPIN & MAGNETISM Electrons are spinning charged particles which generate a tiny magnetic field Only two orientations are possible and they are called spin up or spin down, with clockwise being This is why the 4th Quantum number, ms, is assigned +½ or -½ ELECTRON SPIN Data showed that the He atom was not affected by magnetic field - why? There are 2 e-s present, must be that one is up and one is down, cancelling each others magnetic fields - we say they are "paired" It turns out that only an atom with one or more unpaired e-s exhibits paramagnetism Figure 8.1 Observing the Effect of Electron Spin ELECTRON SPIN The lowest energy state for an e- in H is principal level n = 1 There is only one type of orbital at n = 1, because l = 0, which is an s or a spherical orbital For H, the 1 e- is generally in the 1s orbital In He, there are 2 e-s, and it turns out they are both in the 1s orbital & they are paired up, or coupled with one spin up and one spin down Li or Be: 3rd and 4th e-s are in n = 2, but which type of orbital, s or p? For this we need to look at data for ionization energies IONIZATION ENERGIES Ionization energy (IE): energy required to take an e- away from an atom First IE removes the e- furthest away from the nucleus Examples: IE1 = 1.31 x 106 J/mol for H, 1.68 x 106 J/mol for Fe, and 0.50 x 106 J/mol for Na IONIZATION ENERGIES (IE): IE in MJ/mol e-# 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Na .5 4.6 6.9 9.5 13 17 20 Log 5.7 6.7 6.8 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 8 25 7.4 9 29 7.9 F 1.7 Log 6.2 92 8.0 106 8.03 3.4 6.5 6.1 6.8 8.4 6.9 11 7.0 15 7.2 18 7.3 10 141 8.2 11 178 8.3 Na: three energy levels present as shown by big changes in IE (from 1 to 2, 9 to 10) F: two energy levels with slight difference within level - because of s & p orbital differences (7 to 8) If all the IEs are mathematically adjusted for the increasing force of attraction between protons and remaining electrons: -then we find that the IE1 to IE5 in F are almost equal, meaning that these 5 e-s are "alike" -and that IE6 = IE7 but > IE1 to IE5, so these two e-s are different -and that IE8 = IE9 but >>> IE7, so these two e- levels are really different What does all this mean? IE data define the energy states and orbitals in the atom At n = 1, there's one orbital with e-s that are very hard to remove At n = 2, there are 4 orbitals, but they're different because s has different shape than p Combine the IE data with the known pairing of e-s into 2e- per orbital from magnetic properties and we determine that: s orbital has up to 2 e-s and each p orbital has up to 2 e-s for a total of 6 If F has 5 e- of similar IE – they must be in p orbitals, and they are the easiest to remove so they must be outermost Next 2 e-s are close to same energy, n = 2, but only 2 e-s, so they are in an s orbital The last 2 e-s are very different & have much higher IE, must be close to nucleus, n = 1, 2 e-s in s orbital This data reveals basic e- configuration of F: 1s has 2 e-s, 2s has 2 e-s, 2p has 5 e-s. Now look at Na data: First IE is < 2nd IE, but IE2 to IE9 are about the same; then big jump to IE10 and IE11 Means that: 1 e- is outermost at n = 3; then 8 e-s in n = 2 (notice slight diff for 2s & 2p); n=1 IONIZATION ENERGIES Now we look at first IE vs. atomic number Noble gases have high IE All of Group IA atoms have low IE, Group IIA has fairly low IE Transition metals into same IE - these are d e-s Periodic trend of IE - highest at He, lowest at Fr Figure 8.10 Periodicity of first ionization energy Figure 8.11 First ionization energies of the main-group elements then 2 e-s in Table 8.1 Summary of Quantum Numbers of Electrons in Atoms QUANTUM NUMBERS We know that e-s pair up into two per orbital maximum Pauli Exclusion Principle - a statement of the facts: no two e-s in an atom can have the exact same set of four quantum numbers He 2 e-s: n l ml ms 1 0 0 +½ 1 0 0 -½ ELECTRON CONFIGURATIONS The best way to figure out quantum numbers is to know electron configuration, so we will do that first. There are several “rules” or physical laws based on data like Ionization Energies If 2p is at higher energy level than 2s, then 3p is higher than 3s Also find that 3d is slightly higher than 3p In multi-electron atoms: - 4s slightly lower energy than 3d, so fill 4s before 3d - always start at 1s, fill in according to increasing energy levels Figure 8.3 Order for filling energy sublevels with electrons and a box “illustrating orbital occupancies” that you draw in here: Hund's Rule: max number of unpaired e-s will occur in ground state Two methods: orbital box as seen in previous slide or spectroscopic (spdf) 1s2 Figure page 251 A vertical orbital diagram for the Li ground state (You will do horizontal orbital box notation) __ __ _______ | | | | | | | | etc. 1s 2s 2p ELECTRON CONFIG USING PERIODIC TABLE Remembering all the rules and the order for filling orbitals looks difficult! It turns out the Periodic Table is layed out in blocks: s block is groups 1 & 2; p block is groups 13 to 18; d block is transition elements groups 3 - 12; and f block is inner transition. You can figure out the electron config for the last e- in any element by looking at the periodic table. Then fill in starting from H or nearest noble gas. Figure 8.5 A periodic table of partial ground-state electron configurations Figure 8.6 The relation between orbital filling and the periodic table Practice: pair up and use a plain (not large) periodic table to do the spdf and orbital box notation for B, Ne and Mg. Sample Problem 8.2 (Give the full and condensed electrons configurations, partial orbital diagrams showing valence electrons, and number of inner electrons for the following elements: (a) potassium (b) molybdenum (c) lead ELECTRON CONFIGURATIONS For many e- atoms we can use a shorthand for either method called "noble gas core designation" or condensed version Try for examples: Cl and As ELECTRON CONFIGURATIONS: VALENCE ELECTRONS Electrons beyond noble gas core are valence electrons: e-s in outermost principal quantum level of atom Practice with Na, As, Mn, and Pu Then determine the principal quantum number of last electron in each of the above ELECTRON CONFIGURATIONS Hund’s Rule: max number of unpaired e-s will occur in ground state Why Cr & Cu don't exactly follow the filling rules: Cr is more stable with 1 e- per orbital including 4s Cu is more stable with full d shell and 1 e- in 4s BACK TO QUANTUM NUMBERS If you have the electron configuration, you have the first two quantum numbers for each electron, n and l. An s subshell has only one orbital with only one ml quantum number, 0. A p subshell has three orbitals, so you have to list each one’s ml: -1, 0, +1. A d subshell has ml ranging from -5.,,,0,…+5; etc. Within each orbital, the ms for the first e-is by definition is +½. The second e- is assigned –½. Sample Problem 8.1 Determine a set of quantum numbers for the third electron and a set of quantum numbers for the eighth electron in a fluorine atom. My problem: Make a table of all four quantum numbers for every electron in vanadium. n l ml ms n l ml ms Table 8.2 Partial Orbital Diagrams and Electron Configurations for the Elements in Period 3 Figure 8.4 Condensed ground-state electron configurations in the first three periods Table 8.3 Paartial Orbital Diagrams and Electron Configurations for the Elements in Period 3 Table to remember energy levels IF you don’t have a periodic table handy! (You draw in the arrows.) 1s 2s 2p 3s 3p 3d 4s 4d 4p 4f 5s 5p 5d 5f (5g) 6s 6p 6d 6f (6g) 7s 7p 7d 7f Follow arrows down and to left to fill in electron configuration. HISTORY OF PERIODIC TABLE Origin is based on "periodic properties" and relative masses Johann Dobereiner grouped triads of elements with similar properties and increasing relative mass In 1864, John Newlands conceived the idea of octaves, since the chem prop's seemed to repeat for every eighth element Current table: Julius Meyer and Dmitri Mendeleev Periodic Trends are the result of atom's e- configuration - # of e-s or really # of protons since its arranged by atomic number Look at Argon's e- density vs. distance from nucleus Not like a billiard ball! Radius is "soft" and is affected by covalent bonding, since it can overlap Cl by itself is 132 pm, but in Cl2 radius is 100 pm Trend: smallest radii are upper right, largest to lower left in general Figure 8.7 Defining metallic and covalent radii Figure 8.8 Atomic radii of the main-group and transition elements Figure 8.9 Periodicity of atomic radius Sample Problem 8.3 (Using only the periodic table (not Figure 8.15)m rank each set of main group elements in order of decreasing atomic size: (a) Ca, Mg, Sr (b) K, Ga, Ca (c) Br, Rb, Kr (d) Sr, Ca, Rb PERIODIC TRENDS IE: discussed previously, but trend is for highest to upper right, lowest to lower left. Always endothermic process to remove eElectron Affinity: Trend is most negative EA at F, least likely is Fr, worst are noble gases Table 8.4 Successive Ionization Energies of the Elements Lithium through Sodium Figure 8.13 Electron affinities of the main-group elements Figure 8.14 Trends in three atomic properties Figure 8.15 Trends in metallic behavior Sample Problem 8.4 (Using the periodic table only, rank the elements in each of the following sets in order of decreasing IE1: (a) Kr, He, Ar (b) Sb, Te, Sn (c) K, Ca, Rb (d) I, Xe, Cs Sample Problem 8.5 (Name the Period 3 element with the following ionization energies (in kJ/mol) and write its electron configuration: IE1 IE2 IE3 IE4 IE5 IE6 1012 1903 2910 4956 6273 22,320 ATOMS TO IONS What happens to e- configuration if an atom becomes an ion? Ion size: cations get smaller, anions get bigger More charge is more effect on size ISOELECTRONIC: iso = same, electrons, so same # of electrons We can list isoelectronic series of ions and noble gas atoms that have the same number of electrons. Figure 8.17 Main-group ions and the noble gas configurations ATOMS TO IONS Rank the isoelectronic series on the previous slide by size smallest to largest: Do abbrev. e- config: Mg2+, Fe2+ and Fe3+, Cu1+ and Cu2+. Determine which will be paramagnetic, which is more strongly paramagnetic, etc. Then rank them by size. Sample Problem 8.6 (Using condensed electron configurations, write reactions for the formation of the common ions of the following elements: (a) iodine (b) potassium (c) indium Sample Problem 8.7 (Use condensed electron configurations to write the reaction for the formation of each transition metal ion, and predict whether the ion is paramagnetic. (a) Mn2+ (b) Cr3+ (c) Hg2+ Figure 8.20 Depicting ionic radius Figure 8.21 Ionic vs. atomic radius Sample Problem 8.8 (Rank each set of ions in order of decreasing size, and explain your ranking: (a) Ca2+, Sr2+, Mg2+ (b) K+, S2-, Cl- (c) Au+, Au3+