Zionism

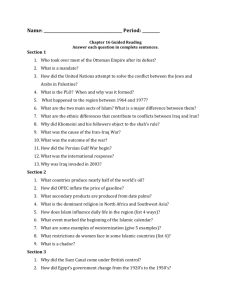

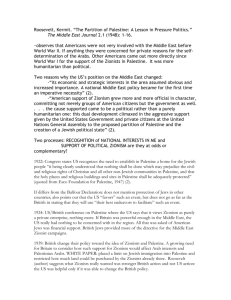

advertisement

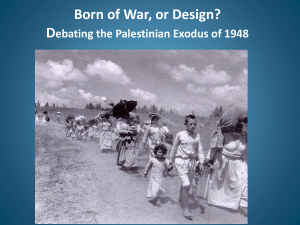

Zionism Zionism is a Jewish nationalist movement that dates from the 19th century. The foremost goal of Zionism, the creation of a Jewish homeland, was achieved with the founding of the state of Israel in 1948. The desire for a Jewish homeland has Biblical origins. Jews believe that over 4,000 years ago, God told Abraham, the founding father of Judaism, to go and occupy Canaan, the land in the Middle East that is Israel and Palestine today. Yet it was not until after the Holocaust of World War II that the Jewish state of Israel was established. That victory for Zionism was bittersweet, however, because the legality of Israel was challenged by Arabs on all sides. That conflict continues to this day. In the mid-1800s, Jewish intellectuals, after suffering and failing to gain complete acceptance into the German, Russian, or Spanish social structures where they lived, began to support the idea that Jews should settle in the region near Jerusalem. Mount Zion is one of the hills surrounding Jerusalem, the holy city, and it was from that sacred mountain that the movement's name was adopted. In Russia in particular, Jews who lived under the harsh regimes of the czars had failed miserably in their attempts to assimilate into the culture. Consequently, they lived in separate communities and spoke their own language, Yiddish. Most of them were poor, although a certain quota were allowed to attend the universities, and a few had become doctors and lawyers. Those autonomous communities had their own schools, businesses, and financial structure. In the mid-19th century, the Russian government all but sanctioned pogroms, bloody grass-roots revolts aimed at Jews. That violence resulted in many Jews escaping to Western Europe and the United States. In 1882, Judah Leib (Leo) Pinsker published, in German, a pamphlet called Auto-Emancipation. Pinsker focused on the dream of establishing a Jewish homeland, but his words fell on deaf ears in most of Western Europe. In Russia, however, a small group inspired by his writing banded together under the name Hovevei Ziyyon, or Lovers of Zion. The Lovers of Zion promoted the idea of Jewish farmers and craftspeople settling in Palestine. Thanks to the generosity of Baron Edmund de Rothschild of Paris, that dream became a reality for a few. From 1882 to 1903, 25,000 Jews migrated to Palestine in what is called the First Aliyah. The Second Aliyah, or next wave, came just before World War I, during 1904-1914, when another 40,000 Jews were added to the population of Palestine. In 1914, there were about 85,000 Jews in Palestine, a small minority among the Arab population. In addition, there were 43 Jewish agricultural settlements with 13,000 settlers, many of them supported by the wealth of the Rothschilds. Theodor Herzl, a journalist from Austria, moved Zionism into the worldwide political arena and is often called the Father of Zionism. In August 1897, he convened the first Zionist Congress in Switzerland. The constitution written at the first Congress stated, "Zionism strives to create for the Jewish people a home in Palestine secured by public law." In 1903, after years of negotiations with the British government, Herzl convinced the United Kingdom of the legitimacy of a Jewish state, and Britain offered 6,000 square miles in the highlands of Uganda. Yet the land in Africa was not the promised land near Jerusalem that many Jews longed for, so any serious consideration of the British proposal began to split the Zionist movement into two factions. Herzl's untimely death at the age of 44 in 1904 marked the end of negotiations with Britain about Uganda, and Zionists were left to focus their hopes on Palestine. The death of Herzl and the onset of World War I contributed to a temporary halt in the Zionist movement. Because the Ottoman Empire (which controlled Jerusalem) was at war with the United Kingdom, and since Herzl had already convinced the British government to sympathize with the Jews, World War I could have been used as on opportunity to rally behind British warfare to garner support for the Zionist movement. However, the Zionists' lack of strong central leadership resulted in a missed opportunity. After World War I, support for Zionism shifted from Germany, Austria, and Russia to London and New York, where money was being raised. Most Zionists who moved to Palestine in the interwar period were from Poland. On November 2, 1917, British foreign secretary Arthur J. Balfour declared his support for the Zionist movement by writing, "His Majesty's Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country." That document, called the Balfour Declaration, was endorsed by the main Allied Powers at the San Remo Conference in 1920 and became an official international policy. Using the Balfour Declaration as a preamble, the council of the League of Nations approved on July 24, 1922 the Palestinian Mandate. The League of Nations also advised how to aid in Jewish immigration to Palestine. However, while the Balfour Declaration had noted the rights of Muslim Arabs in Palestine, the Zionists' goals overshadowed them. Zionists and their supporters did not question the right of Jews to occupy a land that had not been theirs for hundreds of years. The strife among Jews, Palestinians, and other Arabs during the last 50 years of the 20th century proves that short-sighted thinking marred supporters of the Zionist movement, even at the government level of foreign nations. It must be remembered, though, that Britain had enjoyed many successful years of colonization and war victories. The British government thought that it was perfectly acceptable for Jews to "colonize" or occupy Palestine in the same way that the British had conquered and settled areas all over the world. Between 1922 and 1939, the Jewish population in Palestine increased to 30% of the total population, or about 450,000 people. Tel Aviv, a city founded specifically by Jews for Jews, became a major economic center with a population of 150,000. As the Jewish population grew in Palestine, Zionist activists turned toward violent behavior to support their cause. Meanwhile, the anti-Semitic Adolf Hitler gained power at the head of the National Socialist German Workers' Party, or Nazis. The Nazis' mass murder of Jews during World War II did more to bring attention and sympathy to Zionism than any other act of the 20th century. By the time Germany was defeated at the end of the war, surviving Jews all over the world felt that the Old Testament command, given to Abraham to conquer and possess the holy land, had even greater meaning. From the end of World War II in 1945, it took three years to establish Israel as a Jewish state in Palestine. Four major groups were involved in the process: the United Kingdom, which occupied Palestine by mandate of the League of Nations; the United States, a new superpower that had a powerful Jewish voting bloc; the Arab League, which vowed to block the establishment of a Jewish state in the Middle East; and the Zionist Jews from various nations. Each group had its own agenda regarding territorial ownership, government policies, and rights. The British, desiring to maintain good relations with the Arab nations and angered by acts of Zionist terrorism in Palestine, wished to restrict Jewish immigration to Palestine. The United States, however, favored an independent Jewish republic in Palestine. Finally, in 1947, the United Kingdom passed the problem on to the United Nations (UN). The UN Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) recommended that Palestine be partitioned into Jewish and Arab territories but that it maintain the same economic core in an attempt to promote unity and stability in the region. The Arab League immediately protested the recommendation. The Arab nations felt that Jews did not have the fundamental right to live in Palestine just because they needed a place to call home and they wanted that home to be near Jerusalem. Moreover, the territory that UNSCOP recommended for Jewish occupancy included the valuable coast line and farm lands that the Arabs felt was out of proportion to the ratio of Jews and Arabs living in the region. Nevertheless, the UN General Assembly approved the partition on November 29, 1947. The British soon pulled their occupying forces out of the region, and David Ben-Gurion proclaimed the state of Israel on May 14, 1948. The United States and the Soviet Union immediately recognized the new nation. The Arab League, on the other hand, had declared a jihad, or holy war, against the Jews in Palestine. Zionists had achieved their homeland, but that victory set the stage for decades of conflict between Israelis and Palestinians—a conflict that continues to this day. Further Reading Beilan, Yossi, Israel: A Concise Political History, 1992; Gilbert, Martin. Israel: A History. New York: Morrow, 1998; Laqueur, Walter. A History of Zionism. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1972. MLA Citation "Zionism." World History: The Modern Era. ABC-CLIO, 2014. Web. 19 May 2014. View all citation styles. back to top Entry ID: 309421