(Se Young Ahn_Jeong Gon Kim)

advertisement

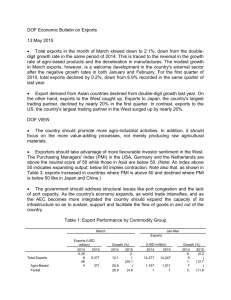

Patterns and Impacts of Korea's Cultural Exports: Focused on East Asia Patterns and Impacts of Korea's Cultural Exports: Focused on East Asia Jeong Gon Kim Se Young Ahn Abstract The main objectives of this paper are, a) to find out how the regional patterns of Korea's cultural goods exports have changed; and b) to find out how Korea's cultural goods exports influence its overall exports to East Asia. During the period from 19962008, Korea’s cultural exports have gradually increased. This has especially been the case from 2001-2008, where, as the Trade Intensity Index (hereafter referred to as the TII) shows, on average East Asian countries are becoming major importers of Korean cultural goods. The empirical results of this paper indicate that a 100% increase in Korean cultural exports to ten East Asian nations leads to increases of overall exports by 4.2-4.7%. The impact of reproducible cultural goods is even higher—5.4-5.8%. These results validate using the exports of cultural goods as a proxy for cultural proximity. Also, the competitiveness of cultural industries is a source of exporting potential in terms of its impact on overall exports as well as in its own right. Key Words: trade in cultural goods, cultural proximity, gravity model, Hallyu Senior Researcher of Korea Institute of International Economic Policy. Professor, Graduate School of International Studies, Sogang University, Korea 1 2 Jeong Gon Ki / Se Young hn I. . Introduction UNESCO (2005) defines trade in cultural goods and services as, “the exports and imports of tangibles and intangibles conveying cultural contents that might either take the form of a good or a service.” Cultural goods and services include “the goods and services which are required to produce and disseminate such content, including cultural equipment and support materials, as well as ancillary services.” The market for cultural goods is arguably one of the most internationalized. In developed countries, household expenditure on recreation and culture accounts for at least 5% of GDP. As of 2005, it was 6.4% in the United States, 7.7% in the United Kingdom and 5.2% in France (Disdier, Tai, Fontagne, and Mayer, 2007). Concurrently, trade in cultural goods has also risen rapidly. World imports of cultural goods increased by 347%—from $47.8 billion to $213.7 billion —between 1980 and 1998 (UNESCO, 2000). The worldwide entertainment and media markets were estimated to be valued at $1,228 billion in 2003 (Price Waterhouse Coopers, 2004). Moreover, trade in cultural goods has become one of the most important issues in institutions concerned with world trade, such as the World Trade Organization (WTO). In the context of East Asia, ‘Hallyu’ reflects the trend of the globalization of cultural industries. Hallyu, a term coined in the late 1990’s by Chinese journalists (Lee, 2002), is used to describe the phenomenon of Korean popular culture becoming vogue, especially in East Asia. In Korea, trade in cultural goods attracts wide attention for two reasons. First, Hallyu, has increased quickly and is now a rising source of Korean exports. The economic potential of cultural industries and the export of cultural goods have been understood since the 1990s. The net profit made by Suiri in the late 1990s, which was the first Korean blockbuster film, was estimated to be the equivalent to the sale of 11,667 Hyundai Sonatas, the representative car of Hyundai Motors. A few years prior to Suiri’s huge success, the economic potential of cultural industries began to receive much attention in Korea, given the commercial success of movies such as Jurassic Park, which was directed by Stephen Spielberg. Second, Korean entrepreneurs and policy makers began to recognize that Hallyu positively affected other Korean exports, especially in the manufacturing industries such as electronics and automobiles. While the export of cultural goods themselves can reap profits, it has the Patterns and Impacts of Korea's Cultural Exports: Focused on East Asia 3 additional benefit of increasing consumption of other Korean-made goods in foreign countries. Therefore Hallyu is considered to be of strategic importance to Korea’s international trade policy. Against this backdrop, the main objectives of this paper are, a) to find out how the regional patterns of Korea's cultural goods exports have changed; and b) to find out how Korea's exports of cultural goods influence overall exports to East Asia. Regarding the latter objective, it is widely acknowledged that exports of cultural goods have a positive impact upon overall exports. However, only a limited number of studies have been conducted, which address this effect using econometric methods, especially ones that focus on Korea and East Asian countries. Moreover, most studies that have been conducted used time-invariant genetic variables to represent cultural closeness. II. Literature Review It has been widely known that cultural closeness (common language, ethnic network, religion, etc.) exerts a positive influence on bilateral trade (for example, see Melitz, 2002; Girma and Yu, 2002; Rauch, 2001, Beugelsdijk, de Groot, Linders, and Slagen, 2004). The primary theoretical reason for this influence, as provided by the literature, is attributed to the reduction of transaction and information costs caused by cultural proximity. Garnaut (1994) argues that linguistic links and other historical and cultural links are particularly important in reducing the cost of unfamiliarity in international trade—so-called psychic costs or subjective resistance. Head and Ries (1998) insist that ‘taste linkage’ reduces transaction costs. Moreover, Disdier et al. (2006) argues that cultural flow or cultural proximity promotes preference formation as well as a reduction in transactional costs. Many academic papers are dedicated to empirically estimating the impact of cultural proximity on overall trade by using time-invariant proxy variables for cultural proximities. According to previous literature, it has been widely accepted that cultural closeness has a positive influence on bilateral trade. There is a long list of proxies of cultural proximity; common language (Melitz, 2003; Fidrmuc and Fidrmuc, 2009), ethnic network (Rauch and Trinidade, 2002; Girma and Yu, 2002), immigrants (Head and Ries, 1998), the social and business network (Rauch, 2001; Wagner, Head, and Ries, 2002), historical links (Eichengreen and Irwin, 1998), a combination of these variables (Felbermayr and Toubal, 4 Jeong Gon Ki / Se Young hn . 2010), cultural similarity index (Hofstede, 2001; Beugelsdijk et al., 2004), mutual trust (Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales, 2009), and genetic similarity (Giuliano, Spilimbergo, and Tonon, 2006). These studies show that cultural proximity positively affects overall trade and other economic transactions. Disdier et al. (2006) and Disdier, Tai, Fontagne and Mayer (2007) conducted pioneering gravity model research that used time-series data of trade in cultural goods as an alternative to genetic cultural variables. Both show that cultural flows (exports of cinematic and cultural goods defined by UNESCO (2005) significantly influence all trade relationships. There are a number of economic papers that deal with Korea's trade in cultural goods. Choe and Park (2008) focus on bilateral relationships; that is, how Korea’s cultural exports to Japan affect overall exports to Japan. They show that trade in cultural goods positively affects overall trade. Kang (2009) analyzes the economic effect Hallyu has on Korea’s exports and investment in ten South East Asian countries from 1997 to 2007. Kang (2009) uses a panel tobit regression model and shows that the impact of Korean cultural exports on overall exports and foreign direct investment is positive and statistically significant. Even though the data of trade in cultural goods based on the HS (Harmonized System) codes does not cover all phenomena of the international flow of culture, it is useful in that most previous studies often used time-invariant genetic variables (dummy indices) which are too simplified to precisely express the extent to which the country pairs are culturally close. With time-series trade data, the changing nature of cultural proximity can be estimated. III. Characteristics of Korea's Exports of Cultural Goods The share of cultural goods in terms of total exports for Korea was about 0.6% as of 2008, based on the UNESCO (2005) categorization. The size of Korea’s cultural exports has gradually increased from about $250 million in 1996 to about $2.25 billion in 2008 (Figure 1). The total amount of Korea’s exports of cultural goods seems to have grown rapidly in that 12 year period. This is at least partially due to the policy since the mid-1990s of promoting cultural industries. The share of Korea’s cultural goods exports as a percentage of the world total has also increased, from about 0.8% in 1996 to about 1.8% in 2008. The importance of Korea in world exports of cultural goods has recently surged. This is mainly due to the rise of Hallyu in East Asia since the mid 1990s. Patterns and Impacts of Korea's Cultural Exports: Focused on East Asia 5 [ Figure 1 ] Korea’s exports of cultural goods, 1996-2008 (unit: million US dollars, percent) Note: The left axis is percentage points, while the right axis is millions of US dollars. Source: UN COMTRADE. The US has been the main importer of Korean cultural goods while Asian countries have also been rising as core importers. Exports to the US constituted about 56% of the total in 1996, but decreased to about 30.5% in 2008. As shown in Table 1, Germany and France have been the main importers of Korean cultural goods in Europe. Meanwhile, the share of exports to ten Asian countries has increased from 26.4% in 1996 to about 37% in 2008. During the same period, the Japanese share has decreased, while those of China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong have dramatically increased. Exports to Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam have also gradually grown. [ Table 1 ] The share of Korea’s exports of cultural goods by partner (unit: percent) Year US 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 55.74 60.00 61.23 63.84 60.27 52.46 55.37 52.11 52.61 33.65 31.55 23.95 30.55 Japan Germany France Taiwan 22.29 14.69 15.35 17.52 21.48 16.45 17.41 17.37 20.80 19.05 13.02 11.30 9.47 0.90 0.55 0.85 0.43 0.22 0.26 4.01 1.03 2.70 1.39 9.64 17.95 19.69 3.21 2.64 2.43 2.09 1.14 2.68 1.43 1.52 4.68 15.63 12.40 0.37 0.67 0.86 1.48 1.96 1.61 0.92 2.09 2.78 3.19 3.23 4.92 3.36 13.28 9.30 Hong Asia China Kong 10 1.81 0.69 26.42 5.53 0.80 23.51 1.08 0.85 20.60 0.73 0.92 22.86 0.57 0.68 26.11 0.84 1.99 25.11 1.62 3.22 29.63 0.78 1.52 27.99 0.91 1.31 28.05 0.68 2.28 29.09 0.87 8.32 26.79 7.62 10.62 48.43 7.29 6.86 36.96 Note: Asia 10 includes China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam and Taiwan. Source: Authors' calculation based on UN COMTRADE and Korea International Trade Association. 6 Jeong Gon Ki / Se Young hn . The trade intensity index (TII) is often used to determine whether the value of trade between two countries is greater or smaller than would be expected on the basis of their importance in world trade. The TII is calculated as follows. TIIij = (xij/Xit)/(xwj/Xwt), where xij and xwj are the values of country i’s exports and world exports to country j. Xit and Xwt refer to country i’s total exports and world total exports, respectively. If the size of TII exceeds unity, these countries have greater bilateral trade than would be expected based on the partners’ shares in global trade and vice versa. The TII shows whether a country exports more (as a percentage) to a given destination than the world does on average. Korea’s TII shows that East Asian countries are becoming major importers of Korean cultural goods (Table 2). During 2001-2008, on average, the TII with China, Indonesia, Japan, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan and Vietnam has a value above unity, which means that these countries have greater bilateral trade than would be expected based on the partner’s share in global trade. [ Table 2 ] Korea’s TII with major importers of Korean cultural goods country Australia Canada China Hong Kong France Germany India Indonesia Italy Japan Malaysia Mexico Netherlands Philippines Russia Saudi Arabia Singapore Taiwan Thailand UAE United Kingdom USA Viet Nam average 1996-2008 0.55 0.22 2.17 0.60 0.66 0.46 0.58 2.32 0.73 4.89 0.79 0.32 0.20 1.05 0.89 0.31 1.24 3.11 0.70 0.15 average 1996-2000 0.65 0.37 1.19 0.90 0.40 0.08 0.42 3.54 0.40 4.49 0.64 0.39 0.03 0.55 0.95 0.26 0.63 1.64 0.74 0.22 average 2001-2008 0.49 0.12 2.78 0.41 0.82 0.70 0.68 1.55 0.94 5.14 0.88 0.27 0.31 1.36 0.85 0.34 1.62 4.03 0.68 0.10 0.14 0.11 0.17 2.14 4.45 2.81 8.43 1.73 1.97 Source: Author’s calculation based on UN COMTRADE and Taiwan Office of Statistics. Patterns and Impacts of Korea's Cultural Exports: Focused on East Asia 7 IV. Empirical Analyses 4.1 Model Specification The gravity model used in this paper is based on Anderson and van Wincoop (2003), which is treated by many trade researchers as an empirical baseline. When using the theoretical gravity model of Anderson and van Wincoop (2003), multilateral resistance needs to be taken into account. However, standard price indices (CPI, PPI, etc.) are not aggregated in the way implied by the theory, and can often be a poor proxy for ideal variables that the theory requires. Due to this problem, many studies commonly add importer and exporter dummies to control multilateral resistance. Moreover, Baldwin and Taglioni (2006) extended the multilateral resistance factor to be applied for panel data and suggested country pair or time-varying country pair dummies as an ideal tool to deal with it. There is still little literature introducing time-varying country pair dummies due to practical problems. However, country pair dummies are sometimes used to deal with the problem. Country pair dummies are used in this empirical research. Because Korea is the only reporter country in our interest, country dummies automatically become country ‘pair’ dummies. Additionally, time (year) dummies are added in all estimations. A random effect model is also considered, but not used in this paper because Hausman tests show that random effect estimators are often not adequate compared with fixed effect estimators. Exports of cultural goods—assumed to be a function of countries’ cultural proximity and affect the total volume of bilateral trade—are used as a proxy for bilateral preferences. A variable of the Linder effect is also employed. Additionally, a bilateral nominal exchange rate is introduced. The basic form of the gravity model estimation including time dummies and country pair dummies is as follows. ln(Xkit) = ß1ln(GDPktGDPit) + ß2ln(LINDkit) + ß3ln(XRkit) + ß4ln(CXkit) + feki + fet + υkit In the equation above, ‘ln’ represents a natural logarithm. GDPktGDPit is the product of Korea’s GDP and the partner countries’ GDP in period t. LINDkit means the Linder effect in a period t. XRkit is nominal exchange rate, the value of a foreign nation’s currency in terms of 8 Jeong Gon Ki / Se Young hn . Korean currency. CXkit is Korea’s exports of cultural goods in period t. We also use RCXkit, which are Korea’s exports of reproducible cultural goods. Xkit is Korea’s total exports to partner countries in period t, which is the value of total exports minus the value of exports of cultural goods in period t. feki and fet are fixed effects of country pair and time (yearly). As country pair dummies are included, time-invariant variables that are specific to a country pair—bilateral distance, common language, and the like, as well as other unobservable characteristics of the country pairs—are subsumed in these country pair dummy variables. As suggested by Baldwin and Taglioni (2006), nominal GDP and export volume data is used. Using real GDP requires trade data to be deflated back to 2000 dollars. Researchers often deflate the trade values back to a common year using, for example, the US price index. This method could cause crucial biases. In order to solve this problem, Baldwin and Taglioni (2006) suggest that the exact conversion factor between US dollars each year can be estimated simply through using time dummies together with nominal GDP and trade data. Heteroscedasticity is corrected according to the method suggested by White (1980). Besides the OLS estimation, the Poisson estimator, suggested by Da Silva and Tenreyro (2006), is used. In the presence of heteroscedasticity, the OLS method can yield biased estimates and the most robust estimation method for multiplicative equations, like gravity, is the PPML technique. In the PPML estimation, the dependent variable is measured in levels. However, it provides estimates that are comparable to elasticity estimates of the linear log specification. 4.2. Data Korea’s exports of cultural goods to ten East Asian countries during 1995-2008 are the main interest of the empirical research in this paper. UNESCO has proposed classifications of cultural products based on the HS codes and the Standard International Trade Code (SITC) codes, and cultural services based on Central Product Classification (UNESCO, 2000, 2005, and 2009). This empirical research employs the HS classification provided by UNESCO (2005). The United Nations COMTRADE database is the main source used to collect data on Korea’s export of cultural goods, as well as total trade. Additionally, Korea International Trade Association (KITA)’s database is used to obtain data for trade with Taiwan, as this is Patterns and Impacts of Korea's Cultural Exports: Focused on East Asia 9 not included in the UN COMTRADE database. Export data can be collected for both exporters and importers. Even though data from the import side is perceived to be more reliable than those from the export side, the export series data is used here because there are some omissions in data from the importers' side. Cultural goods are comprised of two categories: unique cultural goods (such as original paintings, sculptures, and antiques) and reproducible cultural goods (such as recorded music, films, books, and so on. Schulze, 1999). Reproducible cultural goods are produced under strongly increasing returns to scale. In this paper, data of cultural exports is divided into two kinds: total cultural exports and exports of reproducible cultural goods including books, newspapers, other printed materials, recorded media, cinema and photographs and video games. GDP, Linder effect, and nominal exchange rate are used as control variables. The time span of all data is 1995-2008. Additionally, data of 1994 is used to make a one-year lagged variable of cultural exports. All variables used in empirical analyses are natural log forms. A summary of statistics can be seen in Table 3. Sources for the data are below. Nominal GDP data of Korea and ten East Asian countries are collected from the IMF World Economic Outlook Database. Linder effect (absolute value of real GDP difference between Korea and ten Asian countries) is calculated based on real GDP data from the IMF World Economic Outlook Database. Annual average nominal exchange rate is the value of Korean won compared to a unit of partner countries’ currency. Daily exchange rate data are collected from Bloomberg. [ Table 3 ] Summary of statistics Variables ln(Xkit)* ln(CXkit) ln(RCXkit) ln (GDPktGDPit) ln(LINDkit) ln(XRkit) Obs. Mean Std.Dev. Variance Mini. Maxi. 140 22.548 0.914 0.836 21.024 25.237 140 22.548 0.915 0.837 21.024 25.237 140 140 14.745 14.514 2.011 2.027 4.042 4.110 11.343 11.261 19.242 19.188 140 53.363 1.459 2.128 50.637 56.787 140 140 9.1771 3.4538 0.794 2.408 0.630 5.800 4.910 -2.851 9.9935 6.7283 * : ln(Xkit) is divided into two kinds: a) total exports minus cultural exports(above) and b) total exports minus reproducible cultural goods(below). 10 Jeong Gon Ki / Se Young hn . 4.3. Results OLS estimators with country pair and year fixed effects, as suggested by Baldwin and Taglioni (2006), are used first. The results are shown in Table 4. The estimated coefficient of the log of total cultural exports is 0.047, significant at the 5% level. The coefficient of the log of reproducible cultural exports is larger, 0.054, and significant at the 1% level. In the case of both total cultural exports and reproducible cultural products, one-year lagged variables are not significant. The product of GDPs and Linder effect show expected signs at a statistically significant level. The real exchange rates show the expected positive sign, but are not statistically significant. The same analyses were conducted using PPML. Although the overall results are similar with those of OLS estimation, the nominal exchange rates show the expected positive sign in statistically significant levels. In sum, based on analyses using country pair dummies, Korea’s cultural exports have the impact of increasing overall exports. Sizes of coefficients found here are about half the size of those (0.10-0.15) reported by Disdier et al. (2007), which covers almost all countries using time and country dummies. [Table 4 ] Impacts of cultural exports on overall ones CXkit CXkit-1 RCXkit RCXkit1 GDPkt GDPit LINDki XRkit R2 Obs. OLS PPML with country pair fixed effect with country pair fixed effect (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) b b 0.047 0.042 (2.32) (2.35) 0.028 0.025 (1.18) (1.14) 0.054a 0.058a (2.88) (3.71) 0.038 0.018 (1.47) (0.78) 0.775a 0.774a 0.771a 0.775a 0.907a 0.932a 0.870a 0.958a (8.59) (8.03) (8.73) (7.88) (13.68) (12.91) (13.05) (14.61) c c c 0.097 0.099 0.094 0.096c -0.057 -0.054 -0.055 -0.051 (((((-1.44) (-1.37) (-1.40) (-1.21) 1.91) 1.84) 1.88) 1.74) 0.089 0.090 0.080 0.109 0.205a 0.203b 0.203a 0.190b (1.10) (1.04) (1.02) (1.27) (2.76) (2.54) (2.82) (2.41) 0.966 0.965 0.966 0.965 0.981 0.981 0.982 0.981 140 Note 1: Time and country pair dummies are included in (1)-(8). Coefficients on time and country pair dummies are not reported. Note 2: t-values (OLS) and z-values (PPML) are in parentheses. Note 3: a, b, and c denote significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level. Patterns and Impacts of Korea's Cultural Exports: Focused on East Asia 11 V. Conclusion The first objective of this paper is to find out how the regional patterns of Korea's cultural goods exports have changed. This paper shows that the Korean policy of promoting the international competitiveness of cultural industries since the mid-1990s has been effective. Korea’s cultural exports have gradually increased during the period 1996-2008. This is at least partially due to the policy, since the mid-1990s, of promoting cultural industries. Especially during 2001-2008, the TII with East Asian countries, such as China, Indonesia, Japan, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, and Vietnam on average has been at levels above unity. The second question addressed by this paper concerns how Korea's exports of cultural goods influence overall exports to East Asia. The results indicate that Korea’s cultural exports positively affect overall exports to the ten East Asian countries. A 100% increase in Korean cultural exports to these nations increases overall exports to them by 4.2-4.7%. The impact of reproducible cultural goods is even higher—5.4-5.8%. In theoretical terms, these results validate using the exports of cultural goods as a proxy for cultural proximity. On the issue of policy, Korea’s strategy of promoting international competitiveness of cultural industries since the mid-1990s has proven to have been an effective one. Competitiveness of cultural industries is a source of exporting potential in terms of its impact on overall exports as well as in its own right. 12 Jeong Gon Ki / Se Young hn . Appendix 1. UNESCO’s classification of cultural goods Category Cultural Heritage Books Newspapers and Periodicals Other printed Materials HS 96 9705 9706 4901 4903 HS 96 Label Collections and collectors’ pieces Antiques of an age exceeding 100 years Books, brochures, leaflets, etc. Children’s picture, drawing or coloring books 4902 Newspapers, journals, and periodicals 4904 4905 4909 4910 491191 9704 852410 852452 852453 852499 9701 9702 9703 392640 Printed music Maps Postcards Calendars Pictures, designs, and photographs Used postage, etc. Gramophone records Discs for laser-reading systems for reproducing sound only Magnetic tapes recorded (larger ones) Magnetic tapes recorded (smaller ones) Other recorded media Paintings, drawings, pastels, collages, etc. Original engravings, prints, and lithographs Original sculptures and statuary Statuettes and other ornamental articles 442010 Statuettes and other ornamental articles, of wood 6913 Statuettes and other ornamental ceramic articles 852432 Recorded Media Paintings Other Visual Arts 830621 Statuettes and other ornamental articles, of base metal plated with precious metal 830629 Other statuettes and other ornaments, of base metal, etc. 9601 Cinema and Photography Pearl and other animal carving material, etc. 370590 Photographic plates and film, expose and developed 3706 950410 Cinematograph film, exposed and developed Video Games Note 1: According to UNESCO (2000), recorded media includes 852380, 852340, 852329, 852351, and 852359 (HS 1992). Note 2: According to UNESCO (2009), recorded media includes 852410, 852421, 852422, 852423, and 852490 (HS 2007). Source: UNESCO (2005). Patterns and Impacts of Korea's Cultural Exports: Focused on East Asia 13 <References> Anderson, J. E. and E. van Wincoop. 2003. "Gravity and Gravitas: A Solution to the Border Puzzle". American Economic Review 93. 170-192. Baldwin, Richard and Daria Taglioni. 2006. “Gravity for Dummies and Dummies for Gravity Equations.” CEPR Discussion Paper No. 5850. Center for Economic Research (UK). Beugelsdijk, Sjoerd, Henri de Groot, Gert-Jan Linders and Arjen Slangen. 2004. "Cultural distance, institutional distance and international trade," ERSA conference papers. European Regional Science Association. Choe, Jong-il and Soon-Chan Park. 2008. “An Impact of Cultural Goods Export on Total Goods Export: For Korean Exports toward Japan.” Journal of the Korea-Japanese Economics and Management No. 40. The Korea-Japanese Economics and Management Association. (Korean) Da Silva, Santos and Silvana Tenreyro. 2006. “The Log of Gravity.” Review of Economics and Statistics November 2006. 88(4): 641-658. Disdier, Anne-Celia, Thierry Mayer and Silvio Tai,. 2006. "Bilateral Trade of Cultural Goods". mimeo. ______________, Silvio H. T. Tai, Lionel Fontagne and Thierry Mayer. 2007. "Bilateral Trade of Cultural Goods". Centre d'Etudes Prospectives et d'Info. Internationales, Paris. Eichengreen, Barry and Douglas I. Irwin. 1998. "The Role of History in Bilateral Trade Flows". in Jeffrey A. Frankel eds. The Regionalisation of the World Economy. NBER Project Report series. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 33-57. Felbermayr, G. and F. Toubal. 2010. “Cultural Proximity and Trade.” European Economic Review Volume 54, Issue 2, February 2010, 279-293. Fidrmuc, Jan and Janko Fidrmuc. 2009. “Foreign Languages and Trade.” Working paper No. 9-14. Brunel University. Garnaut, Ross. 1994. “Open Regionalism: Its Analytic Basis and Relevance to the International System.” Journal of Asian Economics 5, no. 2 (Summer): 273-90. 14 Jeong Gon Ki / Se Young hn . Girma, S. and Z. Yu. 2002. "The Linkage between Immigration and Trade: Evidence from the United Kingdom". Review of World Economics 138. 115-130. Giuliano, Paola, Antonio Spilimbergo and Giovanni Tonon. 2006. “Genetic, Cultural and Geographical Distances.” CEPR Discussion Papers: 5807. Guiso, Luigi, Paola Sapienza and Luigi Zingales. 2009. “Cultural Biases in Economic Exchange?” Quarterly Journal of Economics August 2009, v. 124-3: 1095-1131. Head K. and J. Ries. 1998. "Immigrant and Trade Creation: Econometric Evidence from Canada". Canadian Journal of Economics 31. 47-62. Hofstede, G. 2001. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations. Second edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. Kang, Han-Gyun. 2009. “An Economic Effect of Korean Cultural Contents on Korea’s Exports and FDI in Southeast Asian Countries.” Journal of Korea Trade Research No.34-1. The Korea Trade Research Association. (Korean) Korea International Trade Association (KITA). Trade Statistics of Korea. Lee, Eunsook. 2002. “A Study of the Popular Korean Wave in China.” Journal of Literature and Film autumn/winter 2002. The Korean Association of Literature and Film. (Korean) Price Water-House and Coopers. 2005. “Global Entertainment and Outlook 2004-2008”. Rauch, J. E. 2001. "Business and Social Networks in International Trade". Journal of Economic Literature 39, 1177-1203. ______________ and V. Trindade. 2002. "Ethnic Chinese Networks in International Trade". Review of Economics and Statistics 84, 2002. 116-130. Schulze, Guenther G. 1999. "International Trade in Art". Journal of Cultural Economics 23, 109-136. Taiwan Statistics Office. http://eng.stat.gov.tw. United Nations. UN COMTRADE Trade Database. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2000. “International Flows of Selected Cultural Goods 1980-1998”. UNESCO. ______________. 2005. “International Flows of Selected Cultural Goods and Services, 19942003: Defining and capturing the flows of global cultural trade”. UNESCO. ______________. 2009. “The 2009 UNESCO Framework for Cultural Statistics”. UNESCO. Patterns and Impacts of Korea's Cultural Exports: Focused on East Asia 15 White, H. 1980. “A Heteroskedasticity-Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimator and a Direct Test for Heteroskedasticity.” Econometrica 48(4): 817-838. Wagner, D., K. Head and J. Ries. 2002. "Immigration and the trade of provinces". Scottish Journal of Political Economy 49. 507-525.