Life in the Middle Ages Feudal Life or safety and for defense, people

advertisement

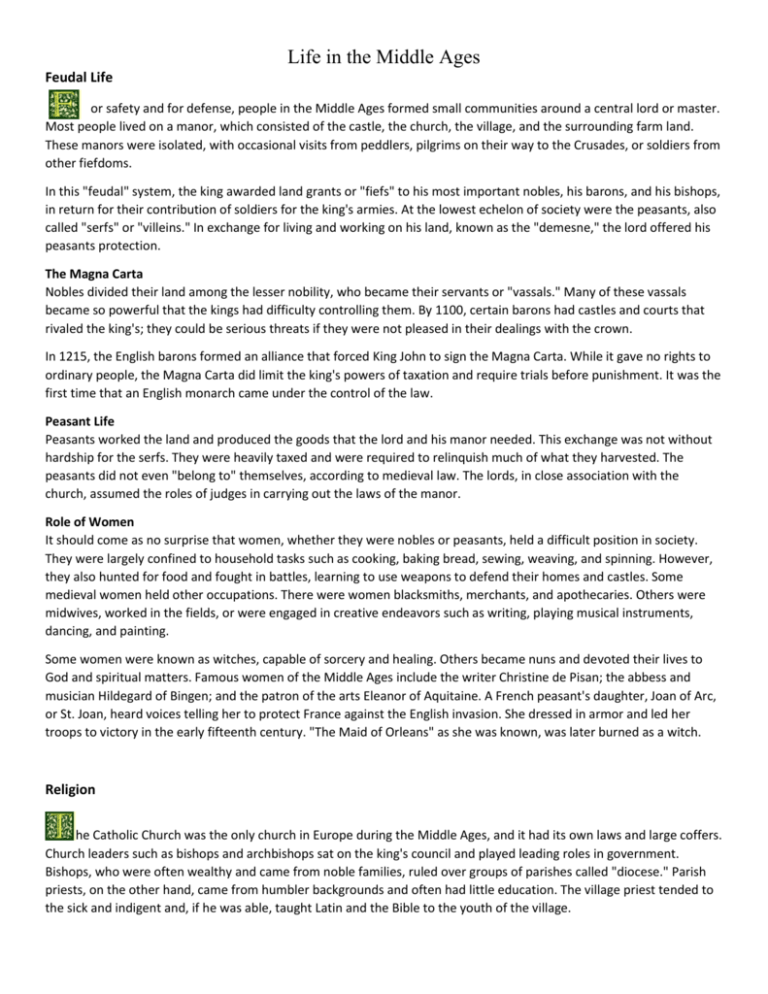

Life in the Middle Ages Feudal Life or safety and for defense, people in the Middle Ages formed small communities around a central lord or master. Most people lived on a manor, which consisted of the castle, the church, the village, and the surrounding farm land. These manors were isolated, with occasional visits from peddlers, pilgrims on their way to the Crusades, or soldiers from other fiefdoms. In this "feudal" system, the king awarded land grants or "fiefs" to his most important nobles, his barons, and his bishops, in return for their contribution of soldiers for the king's armies. At the lowest echelon of society were the peasants, also called "serfs" or "villeins." In exchange for living and working on his land, known as the "demesne," the lord offered his peasants protection. The Magna Carta Nobles divided their land among the lesser nobility, who became their servants or "vassals." Many of these vassals became so powerful that the kings had difficulty controlling them. By 1100, certain barons had castles and courts that rivaled the king's; they could be serious threats if they were not pleased in their dealings with the crown. In 1215, the English barons formed an alliance that forced King John to sign the Magna Carta. While it gave no rights to ordinary people, the Magna Carta did limit the king's powers of taxation and require trials before punishment. It was the first time that an English monarch came under the control of the law. Peasant Life Peasants worked the land and produced the goods that the lord and his manor needed. This exchange was not without hardship for the serfs. They were heavily taxed and were required to relinquish much of what they harvested. The peasants did not even "belong to" themselves, according to medieval law. The lords, in close association with the church, assumed the roles of judges in carrying out the laws of the manor. Role of Women It should come as no surprise that women, whether they were nobles or peasants, held a difficult position in society. They were largely confined to household tasks such as cooking, baking bread, sewing, weaving, and spinning. However, they also hunted for food and fought in battles, learning to use weapons to defend their homes and castles. Some medieval women held other occupations. There were women blacksmiths, merchants, and apothecaries. Others were midwives, worked in the fields, or were engaged in creative endeavors such as writing, playing musical instruments, dancing, and painting. Some women were known as witches, capable of sorcery and healing. Others became nuns and devoted their lives to God and spiritual matters. Famous women of the Middle Ages include the writer Christine de Pisan; the abbess and musician Hildegard of Bingen; and the patron of the arts Eleanor of Aquitaine. A French peasant's daughter, Joan of Arc, or St. Joan, heard voices telling her to protect France against the English invasion. She dressed in armor and led her troops to victory in the early fifteenth century. "The Maid of Orleans" as she was known, was later burned as a witch. Religion he Catholic Church was the only church in Europe during the Middle Ages, and it had its own laws and large coffers. Church leaders such as bishops and archbishops sat on the king's council and played leading roles in government. Bishops, who were often wealthy and came from noble families, ruled over groups of parishes called "diocese." Parish priests, on the other hand, came from humbler backgrounds and often had little education. The village priest tended to the sick and indigent and, if he was able, taught Latin and the Bible to the youth of the village. Life in the Middle Ages As the population of Europe expanded in the twelfth century, the churches that had been built in the Roman style with round-arched roofs became too small. Some of the grand cathedrals, strained to their structural limits by their creators' drive to build higher and larger, collapsed within a century or less of their construction. Monks and Nuns Monasteries in the Middle Ages were based on the rules set down by St. Benedict in the sixth century. The monks became known as Benedictines and took vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience to their leaders. They were required to perform manual labor and were forbidden to own property, leave the monastery, or become entangled in the concerns of society. Daily tasks were often carried out in silence. Monks and their female counterparts, nuns, who lived in convents, provided for the less-fortunate members of the community. Monasteries and nunneries were safe havens for pilgrims and other travelers. Monks went to the monastery church eight times a day in a routine of worship that involved singing, chanting, and reciting prayers from the divine offices and from the service for Mass. The first office, "Matins," began at 2 A.M. and the next seven followed at regular intervals, culminating in "Vespers" in the evening and "Compline" before the monks retired at night. Between prayers, the monks read or copied religious texts and music. Monks were often well educated and devoted their lives to writing and learning. The Venerable Bede, an English Benedictine monk who was born in the seventh century, wrote histories and books on science and religion. Pilgrimages Pilgrimages were an important part of religious life in the Middle Ages. Many people took journeys to visit holy shrines such as the Church of St. James at Santiago de Compostela in Spain, the Canterbury cathedral in England, and sites in Jerusalem and Rome. Chaucer's Canterbury Tales is a series of stories told by 30 pilgrims as they traveled to Canterbury. Homes ost medieval homes were cold, damp, and dark. Sometimes it was warmer and lighter outside the home than within its walls. For security purposes, windows, when they were present, were very small openings with wooden shutters that were closed at night or in bad weather. The small size of the windows allowed those inside to see out, but kept outsiders from looking in. Many peasant families ate, slept, and spent time together in very small quarters, rarely more than one or two rooms. The houses had thatched roofs and were easily destroyed. Homes of the Wealthy The homes of the rich were more elaborate than the peasants' homes. Their floors were paved, as opposed to being strewn with rushes and herbs, and sometimes decorated with tiles. Tapestries were hung on the walls, providing not only decoration but also an extra layer of warmth. Fenestral windows, with lattice frames that were covered in a fabric soaked in resin and tallow, allowed in light, kept out drafts, and could be removed in good weather. Only the wealthy could afford panes of glass; sometimes only churches and royal residences had glass windows. The Kitchen In simpler homes where there were no chimneys, the medieval kitchen consisted of a stone hearth in the center of the room. This was not only where the cooking took place, but also the source of central heating. In peasant families, the wife did the cooking and baking. The peasant diet consisted of breads, vegetables from their own gardens, dairy products from their own sheep, goats, and cows, and pork from their own livestock. Often the true taste of their meat, salted and used throughout the year, was masked by the addition of herbs, leftover breads, and vegetables. Some vegetables, such as cabbages, leeks, and onions became known as "pot-herbs." This pottage was a staple of the peasant diet. Life in the Middle Ages The kitchens of manor houses and castles had big fireplaces where meat, even large oxen, could be roasted on spits. These kitchens were usually in separate buildings, to minimize the threat of fire. Pantries were hung with birds and beasts, including swans, blackbirds, ducks, pigeons, rabbits, mutton, venison, and wild boar. Many of these animals were caught on hunts. Garbage and Disposal Current archaeological studies of sewage and rubbish pits contribute to our understanding of what medieval people ate. One of the most informative pits was found in Southampton, England. This pit belonged to a prominent merchant. It contained the remains of berries, fruits, and nuts, as well as pottery, glass, and fabrics, including silk, from Europe and the Near East. It also contained the remains of a Barbary ape. Documents found at the site describe the family's consumption of meat, use of pewter utensils, and love of music. Evidence that butchery took place during this time was also found in these documents. Health s the populations of medieval towns and cities increased, hygienic conditions worsened, leading to a vast array of health problems. Medical knowledge was limited and, despite the efforts of medical practitioners and public and religious institutions to institute regulations, medieval Europe did not have an adequate health care system. Antibiotics weren't invented until the 1800s and it was almost impossible to cure diseases without them. There were many myths and superstitions about health and hygiene as there still are today. People believed, for example, that disease was spread by bad odors. It was also assumed that diseases of the body resulted from sins of the soul. Many people sought relief from their ills through meditation, prayer, pilgrimages, and other nonmedical methods. The body was viewed as a part of the universe, a concept derived from the Greeks and Romans. Four humors, or body fliuds, were directly related to the four elements: fire=yellow bile or choler; water=phlegm; earth=black bile; air=blood. These four humors had to be balanced. Too much of one was thought to cause a change in personality--for example, too much black bile could create melancholy Medicine was often a risky business. Bloodletting was a popular method of restoring a patient's health and "humors." Early surgery, often done by barbers without anesthesia, must have been excruciating. Who was Treated and Who Did the Treating Medical treatment was available mainly to the wealthy, and those living in villages rarely had the help of doctors, who practiced mostly in the cities and courts. Remedies were often herbal in nature, but also included ground earthworms, urine, and animal excrement. Many medieval medical manuscripts contained recipes for remedies that called for hundreds of therapeutic substances--the notion that every substance in nature held some sort of power accounts for the enormous variety of substances. Many treatments were administered by people outside the medical tradition. Coroners' rolls from the time reveal how lay persons often made sophisticated medical judgments without the aid of medical experts. From these reports we also learn about some of the major causes of death. Humors Natural functions, such as sneezing, were thought to be the best way of maintaining health. When there was a build-up of any one humor, or body fluid, it could be disposed of through sweat, tears, feces, or urine. When these natural systems broke down, illness occurred. Medieval doctors stressed prevention, exercise, a good diet, and a good environment. One of the best diagnostic tools was uroscopy, in which the color of the patient's urine was examined to determine the treatment. Other diagnostic aids included taking the pulse and collecting blood samples. Treatments ranged from administering laxatives and diuretics to fumigation, cauterization, and the taking of hot baths and/or herbs. Life in the Middle Ages Surgery Performed as a last resort, surgery was known to be successful in cases of breast cancer, fistula, hemorrhoids, gangrene, and cataracts, as well as tuberculosis of the lymph glands in the neck (scrofula). The most common form of surgery was bloodletting; it was meant to restore the balance of fluids in the body. Some of the potions used to relieve pain or induce sleep during the surgery were themselves potentially lethal. One of these consisted of lettuce, gall from a castrated boar, briony, opium, henbane, and hemlock juice--the hemlock juice could easily have caused death. Town Life ollowing 1000, peace and order grew. As a result, peasants began to expand their farms and villages further into the countryside. The earliest merchants were peddlers who went from village to village selling their goods. As the demand for goods increased--particularly for the gems, silks, and other luxuries from Genoa and Venice, the ports of Italy that traded with the East--the peddlers became more familiar with complex issues of trade, commerce, accounting, and contracts. They became savvy businessmen and learned to deal with Italian moneylenders and bankers. The English, Belgians, Germans, and Dutch took their coal, timber, wood, iron, copper, and lead to the south and came back with luxury items such as wine and olive oil. With the advent of trade and commerce, feudal life declined. As the tradesmen became wealthier, they resented having to give their profits to their lords. Arrangements were made for the townspeople to pay a fixed annual sum to the lord or king and gain independence for their town as a "borough" with the power to govern itself. The marketplace became the focus of many towns. Forming Town Governments As the townspeople became "free" citizens, powerful families, particularly in Italy, struggled to gain control of the communes or boroughs. Town councils were formed. Guilds were established to gain higher wages for their members and protect them from competitors. As the guilds grew rich and powerful, they built guildhalls and began taking an active role in civic affairs, setting up courts to settle disputes and punish wrongdoers. The new merchant class included artisans, masons, armorers, bakers, shoemakers, ropemakers, dyers, and other skilled workers. Of all the craftsmen, the masons were the highest paid and most respected. They were, after all, responsible for building the cathedrals, hospitals, universities, castles, and guildhalls. They learned their craft as apprentices to a master mason, living at lodges for up to seven years. The master mason was essentially an architect, a general contractor, and a teacher. The First Companies The population of cities swelled for the first time since before the Dark Ages. With the new merchant activity, companies were formed. Merchants hired bookkeepers, scribes, and clerks, creating new jobs. Printing began in 1450 with the publication of the Bible by Johannes Gutenberg. This revolutionized the spread of learning. Other inventions of the time included mechanical clocks, tower mills, and guns. The inventions of Leonardo da Vinci and the voyages of discovery in the fifteenth century contributed to the birth of the Renaissance. Few serfs were left in Europe by the end of the Middle Ages, and the growing burgher class became very powerful. Hard work and enterprise led to economic prosperity and a new social order. Urban life brought with it a new freedom for individuals.