personal experiences with regard to gen malan

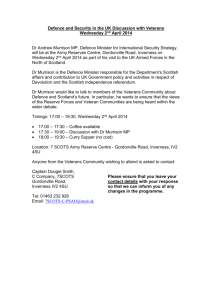

advertisement