Abstracts - Flinders University

advertisement

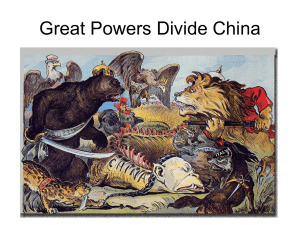

Abstracts Dr. Richard Scully, DECRA Fellow, History, University of New England Shaping Satire: The importance of medium for the history of the political cartoon This paper explores the importance of artistic medium when considering the history and development of the political cartoon. While hand-drawing has for centuries been the fundamental basis for all graphic political satire, the mass reproduction and distribution of such satires has been dependent upon changing technologies of printing, since its adoption in Europe in the late fifteenth century. The final, printed version of a cartoon or caricature has (until very recently) always been the finished product of the creative process; however, the means by which that end result has been attained has undergone a series of quite radical transformations over the past five or so centuries. From early woodblock printing, via copper etching, lithography, improved woodcuts, photolithography, steel newsprinting, and laser printing, to 21st-century digital, online mediums, the possibilities and limits of each medium have enabled as well as restricted graphic, satirical expression. The demands of these processes have to a considerable extent impacted upon the ultimate form and content of the political cartoon, determining what could/could not be depicted or said. Therefore, any account of the political cartoon should treat technology and medium as being just as important as other factors (levels of literacy, mechanisms of censorship or free-expression, artistic conventions, and cartoonists' own biographies) in the history of the art form. Assoc. Prof. Robert Phiddian, English, Flinders University The revolution in political cartoons and the early Australian The 1950s were a quiet time for political cartooning in Australia. The weeklies were long past their best, and daily newspapers (including the Age, hard though that is to believe now) often lacked editorial cartoons entirely, making do with caricatures and apolitical ‘funnies’ for comic relief. Only George Molnar at the Sydney Morning Herald commanded a prominent place for visual satire, and even his focus was often more on social than political critique. In the 1960s Australian political cartoons were transformed by three major events: the arrival of Les Tanner at the Bulletin, after Donald Horne was given the job of reviving it by Frank Packer; the radically new style and content of Bruce Petty’s cartoons during The Australian’s first decade; and the development of a stable of cartoonists at the Age under Graham Perkin. It is in this period that the now common assumption that cartoonists are ‘always left-wing’ came into being, an irony hard to miss in the light of the broad career arcs of Packer and Rupert Murdoch. This paper will focus on the middle part of this narrative, particularly on the impact of Bruce Petty’s visually and politically radical cartooning for The Australian from day one until the Whitlam years. It will do so both by sketching a narrative of visual experiment (within the frame of the editorial cartoon and, by extension, to the ‘look and feel’ of the paper) and by looking closely at the controversy surrounding an Anzac Day cartoon in 1969. In what ways can Petty’s work be said to incarnate the anti-establishment ‘ethos’ of the young newspaper? What were the visual and political consequences for other broadsheets? How did this ‘left-wing’ impetus end at The Australian and live on in other papers for decades?