Sustainability and entrepreneurial action

advertisement

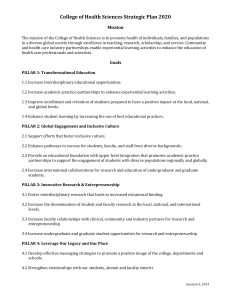

Sustainability and Entrepreneurial Action Steffen Korsgaard, PhD Department of Management, CORE Aarhus School of Business, Aarhus University Haslegaardsvej 10 8210 Aarhus V E-mail: stk@asb.dk Alistair R Anderson Centre for Entrepreneurship Robert Gordon University Aberdeen a.r.anderson@rgu.ac.uk Paper to be presented at The 33rd Annual ISBE Conference, London, 3-4 November 2010 Keywords: entrepreneurship, sustainability, resources, case study Abstract Objectives – This paper explores how entrepreneurial action can lead to environmental sustainability. It builds on the assumption that the creation of sustainble practices is one of the most important challenges facing the global society, and that entrepreneurial action is a vital instrument in the pursuit of sustainability. Prior Work – Extant literature identifies two main approaches to sustainable entrepreneurship. (i) traditional exploitation of environmentally relevant opportunities and (ii) institutional entrepreneurship creating opportunities. We identify a novel form: resource oriented sustainable entrepreneurial action. Approach – The paper uses a case study approach to build deeper theoretical knowledge of environmentally sustainable entrepreneurship. Results – The paper identifies and analyses a distinct form of sustainable entrepreneurship - resource oriented entrepreneurship - which uses bricolage in various ways to create sustainable solutions. Implications and value – The concept of resource oriented sustainable entrepreneurship contributes to the theoretical understanding of how entrepreneurial action can support sustainability, Furthermore the case study has significant learning points for practitioners and academics alike. 1 Introduction Entrepreneurship, the pursuit of business opportunities, may appear at odds with the long term perspectives of sustainability (Anderson, 1998; Mackelworth & Carić, forthcoming). Indeed, it is easy to think of entrepreneurs who have caused considerable environmental damage. It seems that entrepreneurs, exploiting opportunities in the pursuit of profits, are unlikely to have “practices that are sustainable if they are in harmony with or enhance both current and future potential to meet human needs and aspirations” (World Commission on Environment, 1987). Nonetheless, perhaps because the unique ability of entrepreneurs to innovatively combine self and circumstance (Anderson, 2000), researchers are exploring entrepreneurship as a potential mechanism for sustainable development (Harbi, Anderson, & Ammar, 2010). Concepts such as sustainable entrepreneurship (Cohen & Winn, 2007; Dean & McMullen, 2007), ecopreneurship (Schaper, 2002) and social entrepreneurship (Dorado, 2006) all express the hope that entrepreneurs will provide solutions to the multiple environmental problems facing both developed and developing economies. But despite this increasing interest in linking entrepreneurship and sustainability, sound theoretical understanding of the link is only emergent (York & Venkataraman, forthcoming). It is this gap that we want to address. We ask how entrepreneurship can contribute to sustainability and how we might understand this. We first explore the concepts of sustainability and entrepreneurship to argue that the notion of resources links the concepts. This provides us with a theoretical framework to explore our case study. We find that, in this case, the essence of sustainability is entrepreneurial re-sourcefulness. One typical approach to this research problematic is to ask whether there are certain types of entrepreneurial action that are particularly conducive to the creation of sustainable solutions (Anderson, 1998; Dean & McMullen, 2007; Pacheco, Dean, & Payne, forthcoming). This view is premised on the basis that some entrepreneurs are motivated by sustainability. But this view takes a rather individualistic perspective. Taking a broader view, an economic perspective, entrepreneurship scholars have suggested that unsustainable practices can be seen as a result of market inefficiencies and the entrepreneurial action to rectify such inefficiencies can be seen as sustainable entrepreneurship (Cohen & Winn, 2007; Dean & McMullen, 2007). Similarly, institutional entrepreneurship has explored how entrepreneurs can create new institutional structures that provide incentives for sustainable action (Pacheco et al., forthcoming). In this paper we propose a novel form of environmentally sustainable entrepreneurial action that we believe contributes to understanding sustainability. Existing research into sustainable entrepreneurship has largely focused on how entrepreneurs can create and/or exploit environmentally relevant profit opportunities within a market structure. However we suggest that the environmental problems facing the global community are not simply market failures and consequently cannot be overcome only through traditional business entrepreneurship (e.g. Kirzner, 1973; Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). Our argument is that in order to gain a full understanding of the range of sustainable entrepreneurship, we must explore forms of entrepreneurial action that are resource oriented and seek to make the most of the resources at hand (Baker & Nelson, 2005). Such forms incorporate a more frugal attitude to resources and economic growth and may embody life style changes that run counter to the western consumption logic (Gerlach, 2003; Sachs, 1999). It also runs counter to a conventional view, where entrepreneurship is conceived as the pursuit of opportunity without regard to resources currently available (Stevenson & Jarillo, 1990). Instead we argue that the heart of sustainable entrepreneurship lies precisely in parsimony in resources. In this paper we explore resource oriented sustainable entrepreneurship through a case study of an entrepreneur. For many years the entrepreneur in question, Steen Møller, has engaged in a series of projects, all of which emphasise environmental sustainability as an important feature. The entrepreneurial practices of Steen Møller thus constitute a relevant and critical case (Yin, 2009) for exploring the link between entrepreneurial action, resources and sustainability. The paper thus makes three contributions to the field of sustainable entrepreneurship. Firstly, it proposes, conceptualises and explores empirically a new form of sustainable entrepreneurial action. Secondly, it thus enhances our theoretical understanding of how entrepreneurial action can help solve environmental problems (York & Venkataraman forthcoming). Finally, it adds depth to the theoretical understanding of sustainable entrepreneurship by building theory from an in depth case study of entrepreneurial action. It differs from much research which has relied on examples and secondary data (see e.g. Dean & McMullen, 2007; Pacheco et al., forthcoming; York & Venkataraman, forthcoming). 2 Entrepreneurship and sustainability Extant literature on (environmentally) sustainable entrepreneurship as focused on three main areas: (i) the existence, discovery and exploitation of environmentally relevant opportunities (Cohen & Winn, 2007; Dean & McMullen, 2007; York & Venkataraman, forthcoming); (ii) institutional entrepreneurship addressing the incentives to act in a sustainable way for new and existing organisations (Dean & McMullen, 2007; Pacheco et al., forthcoming) and (iii) the cognitive and psychological setup of the eco-entrepreneur (Krueger, 1998; Kuckertz & Wagner, forthcoming). As such this literature mirrors the dominant trends within the broader field of entrepreneurship research in its current emphasis on the processual and cognitive aspects of opportunity discovery and exploitation (Mitchell, Busenitz, Lant, McDougall, Morse, & Smith, 2004; Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). Our paper is located in this in this context but we are particularly interested in entrepreneurial action. Nonetheless we acknowledge that such aspects, cognitive, psychological and motivational, are important underlying factors influencing all forms of environmentally sustainable entrepreneurial action. The relationship is shown in figure 1 below. For environmentally sustainable entrepreneurial action, Pacheco et al. identify two types; firstly, the discovery and exploitation of environmentally relevant opportunities. This is structurally similar to the traditional view of the profit seeking alert entrepreneur found in the Austrian tradition (Hayek, 1945; Kirzner, 1973)1 and more recently in the nexus perspective of entrepreneurship (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000; Venkataraman, 1997; York & Venkataraman, forthcoming). Secondly, the creation of opportunities for sustainable entrepreneurship through institutional entrepreneurship which changes the “rules of the game” (Aldrich & Fiol, 1994). Pacheco et al. suggest that the latter form of entrepreneurial action is often a precursor to the former, as the opportunities created by institutional entrepreneurs subsequently require discovery by Austrian type entrepreneurs. While both these types of entrepreneurial action are focused on economic transactions and profit opportunities in the market, there are significant analytical differences between them. Figure 1: Sustainable entrepreneurship Exploitation of environmentally relevant profit opportunities Institutional entrepreneurship – changing political, market and other institutional settings Resource oriented sustainable entrepreneurship Cognitive and psychological aspects of sustainable entrepreneurs 1 It has recently been suggested by entrepreneurship scholars that the dominant interpretation of Kirzner and other Austrian economists overemphasizes the role of discovery and overlooks how the Austrians also emphasize the creative and speculative aspects of entrepreneurial action. See Berglund, H. 2009. Austrian economics and the study of entrepreneurship: concepts and contributions, Academy of Management Conference. Chicago, Ill, Chiles, T. H., Bluedorn, A. C., & Gupta, V. K. 2007. Beyond Creative Destruction and Entrepreneurial Discovery: A Radical Austrian Approach to Entrepreneurship. Organization Studies, 28(4): 467-493, Klein, P. G. 2008. Opportunity Discovery, Entrepreneurial Action, and Economic Organization. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 2(3): 175-190. Korsgaard, S., Berglund, H., Thrane, C., & Blenker, P. 2010. A tale of two Kirzners: Time, uncertainty and the 'nature' of opportunities, 16th Nordic Conference on Small Business Research. Kolding, Denmark. 3 Within any discussion of sustainable entrepreneurship as the discovery and exploitation of environmentally relevant opportunities, it is assumed that when economic activity results in environmental degradation this is a result of market failures or market imperfections. Examples of such market failures include inefficient firms, externalities, flawed pricing mechanisms, information asymmetries, public goods, monopoly power and inappropriate governmental intervention (Cohen & Winn, 2007; Dean & McMullen, 2007). The existence of market failures by definition incorporate opportunities for profit if entrepreneurs can overcome the relevant barriers for a better functioning of the market for goods with environmental implications (Dean & McMullen, 2007). Examples of profit motivated entrepreneurial action with positive environmental consequences include the establishment and exploitation of excludability for public goods (Dean & McMullen, 2007) or mediating information asymmetries by providing superior information concerning environmental effects of products (Cohen & Winn, 2007). In both cases this will provide the entrepreneur with a competitive advantage. Sustainable entrepreneurship, as pointed out above, involves a change in the institutional settings which define the incentives, the norms and values, to act in an environmentally responsible way. Pacheco et al. suggest that in many areas a kind of “green prison” exists where actors are induced to take the less environmentally unsustainable option, e.g. because it is cheapest or easiest, even though in the long run it may be less rational, the “tragedy of the commons”. An example of this could be overfishing, which may result in short term economic gain but will eliminate the long terms prospects of fishing. Institutional entrepreneurs act to change the incentives of the institutional setting by reducing the benefits of environmentally unsustainable strategies and/or enhancing the benefits of the environmentally sound strategies (Pacheco et al., forthcoming, p. 6). Various ways of changing the institutional structure exist. Building on studies of economic institutions, Pacheco et al. suggest that changing institutional norms, establishing property rights of public or social goods and government legislation are the most relevant measures. Dean and McMullen (2007) further suggest that the elimination of environmentally damaging government subsidies is perhaps the most important form of sustainable institutional entrepreneurship. Common across all these types of entrepreneurial agency is that they involve collective action of some form (Aldrich & Fiol, 1994), and that they are therefore different in nature from the more traditional opportunity discovering form of entrepreneurship (Aldrich & Fiol, 1994; Pacheco et al., forthcoming). This does not mean, however, that these institutional entrepreneurs are not driven by profit. Quite the contrary; often the opportunities created through institutional change will be exploited through a traditional form of entrepreneurial action by the very same individuals or organizations that acted as institutional entrepreneurs (Dean & McMullen, 2007; Pacheco et al., forthcoming). The relation between the two forms of environmentally sustainable entrepreneurship identified by Pacheco et al. and described above is depicted in figure 1. Yet, we suggest that the role of entrepreneurial action in fostering sustainability and environmentally sustainable practices is far from exhausted by the two forms described above. A third form of environmentally sustainable entrepreneurship exists, and adds considerable theoretical purchase to market and opportunity oriented entrepreneurship. As will be demonstrated below in the case study of Steen Møller, this third form of sustainable entrepreneurship exists in practice and therefore warrants theoretical exploration. Moreover, we suggest that this form of entrepreneurial action is important for multiple reasons. Firstly, contrary to the belief implicit in opportunity and market oriented forms of sustainable entrepreneurship, we do not believe that all environmental problems can be resolved through economic action and not all material elements involved in environmental problems and solutions can be transformed into a form that allows market transaction. Furthermore, the coupling of economic development and sustainability is not as unproblematic as it would seem in the extant literature on sustainable entrepreneurship. Market and opportunity oriented sustainable entrepreneurship suggest that environmental degradation is solely a result of market failures, and can be solved through an optimized resource allocation (brought about through entrepreneurial action), yet as pointed out by sustainability scholars (Heidenreich, 2009; Nath, Hens, & Pimentel, 1999; Sachs, 1999), a real solution to the environmental challenge facing the planet requires “reduced production and consumption and accepting a more modest and less polluting life-style” (Nath et al., 1999). The environmental crisis it thus not solely a crisis of pollution (negative externalities) but also a crisis of resource scarcity and a result of seeing the use, acquisition, and disposal of resources as a matter of secondary importance. 4 An example of market and opportunity focused entrepreneurship research is Stevenson and Jarillo’s (1990, p. 23) definition of entrepreneurship as “a process by which individuals - either on their own or inside organizations - pursue opportunities without regard to the resources they currently control”. This quotation in many ways set the tone for the two decades of entrepreneurship research that was to come and of which the two market and opportunity oriented forms of sustainable entrepreneurship are prime examples. Yet, as suggested above entrepreneurial action can also be resource oriented. This has been discussed recently within the entrepreneurship field under the headings of bricolage (Baker, 2007; Baker, Miner, & Eesley, 2003; Baker & Nelson, 2005; Garud & Karnøe, 2003; Phillips & Tracey, 2007) and effectuation (Sarasvathy, 2001). The concepts of bricolage and effectuation suggest that entrepreneurs take their starting point in currently available resources and create effects from these resources. So rather than seeking out and identifying opportunities in the market, such entrepreneurs create opportunities from the resources at hand (Baker & Nelson, 2005). This entails a more frugal attitude towards resources, and holds great potential for a more environmentally sustainable form of entrepreneurship (Archer, Baker, & Mauer, 2009). This form of entrepreneurial action moves resources and creative use of resources to create new practices, products etc. to the forefront. We will therefore suggest that a complete understanding of how entrepreneurial action can promote sustainability must also include a resource oriented form of environmentally sustainable entrepreneurial action. From a resource oriented perspective entrepreneurship is seen as the creation and extraction of value from an environment (Anderson, 1998; Anderson & McAuley, 1999; Jack & Anderson, 2002). Whether this action involves an opportunity for profit or not becomes a secondary matter, but the approach opens space for seeing sustainable entrepreneurial action as something that can possibly be enacted in everyday practices (Steyaert & Katz, 2004). By focusing on creative recombinations of resources at hand, entrepreneurial action can take place in any given setting where individuals and groups are interested in improving the environment. Such activities are presented and discussed in our case study of an entrepreneur who has a long history of engaging in resource oriented sustainable entrepreneurship; Steen Møller. Methods This paper uses a case study approach to build theoretical understanding of resource oriented environmentally sustainable entrepreneurship. As indicated above the theoretical understanding of both resource oriented and other forms of sustainable entrepreneurship is limited (York & Venkataraman, forthcoming). This makes exploratory case studies a suitable methodological choice (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2009), as such studies allow for an in depth study of a phenomenon in its context (Yin, 2009). The case, ecopreneur Steen Møller, has been selected using a critical case strategy (Flyvbjerg, 2004). The value of a critical case is determined, not by how it is representative of a larger population, but by the amount of information and learning the can be derived from the case (Flyvbjerg, 2004; Stake, 2000). Steen Møller thus represents a critical case because he has engaged in a long series of different projects all embodying resource oriented entrepreneurial action, where value has been created and extracted from the environment (Anderson, 1998; Jack & Anderson, 2002). Studying Steen Møller will thus allow us to see the phenomenon in a variety of instantiations as well as observe the antecedents and effects of the phenomenon. Data collection consisted of three interviews with Steen, combined with secondary data in the form of TV programmes and newspaper articles documenting Steen’s projects. The data has been coded using an open coding approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) to identify the different instances of resource oriented environmentally sustainable practices in which Steen have been involved. Steen Møller Steen Møller is now a well known character in Denmark, mostly due to his many appearances on television. He was first portrayed in the mid-nineties in a documentary which featured Steen showing his unique house and telling his story of how he came to build the house. The house was built using recycled or unprocessed materials often acquired locally. The house had cost only a fraction of the normal costs of a normal 200 m2 house. This unusual project grew from Steen’s prior experiences with being an organic farmer and folkschool warden. Steen had taken part in an organic farming cooperative, but found that the economic pressures of mortgages and making ends meet had undermined the joy of farming. Eventually, the pressure was too much for Steen and he left farming. The solution, as it came to Steen, was to become debt-free. 5 Without the expenses of a mortgage, he would be free to undertake only that which he actually wanted to do, instead of what was necessary to make ends meet. This solution entailed building a house without taking out a loan; i.e. very cheaply. As standard building materials are typically heavily processed, they are also very expensive. Therefore, Steen was forced to find unprocessed local materials either readily available in the area or recycled. Such materials are typically organic and sustainable. In Steen’s project his own economic sustainability went hand in hand with environmental sustainability. The successful TV appearance and the friendship with the journalist responsible for the documentary, Anton Gammelgaard lead Steen and Anton to form the Friland project. This project would feature 13 families building new homes and new lives in a rural area, with Danmarks Radio (DR) following the whole process closely in TV, radio and web broadcasts. With the involvement of DR and Rønde Municipality (the local authority) the project was quickly realised and in 2001 the first families moved into caravans on a cornfield just outside the village of Feldballe. Anton Gammelgaard had proposed to DR that Friland was meant to be an “exploratorium for building and business development in rural villages” and was to create “the global village of the future”. As such, Anton and Steen envisaged Friland as a response to emergent social trends and challenges in contemporary society, including: environmental sustainability, depopulation of the rural areas, the increasing debt burden on families as they buy houses, the change from an industrial society to an information society and changes in the labour market (people moving from wage labour to self-employment). Friland was thus presented as a response to these challenges by weaving together pre-industrial building methods, unprocessed building materials and modern information technology into a package that would allow people to be more free in choosing to live and work, as they were freed from the burden of monthly mortgage payments. Friland literally means “Freeland”. The idea was that this would result in interesting new ways of organising as individuals, families and community. The entrepreneurial practices of Steen As the entrepreneurial process of realising the Friland project has been documented elsewhere (Korsgaard, 2009; Korsgaard & Anderson, forthcoming) this article focuses on some of the more recent entrepreneurial activities of Steen including the building of his “new” house at Friland and a recent project involving housing improvement in Nepal. Visiting Steen at his house at Friland is a fascinating experience. The surroundings of his house appear at first glance to be rather messy. His lot is scattered with used materials of all sorts, which seem to have been collected over a long period. The inside of his house, on the other hand gives a completely different impression, and were it not for the beautiful dome of the living room, and the rugged beauty of the clayplastered walls and raw timber, it would resemble most family-homes. In building his house at Friland and creating his unique way of life, Steen has sought to bring his resource consumption down to 10-20% of the average in the developed countries. This 10-20% equals what would be reality if all people were to share the natural resources of the earth equally. He has achieved this in all aspects of his living with the exception of transportation. This would require a car that can drive 200 kilometres per litre. The house is built from bales of straw and plastered with clay. The load bearing structure is made from wood from a local forest. The floor consists of a 75 cm layer of clam-shells which provides insulation and surfaced with sand and clay. The walls are made from straw bales placed on clam-shells and covered with clayplaster. The roof is made from a recycled plastic membrane topped by a layer of clam-shells and a plant cover. The clam-shells used for Steen’s house – as well as many other houses at Friland – are waste or byproducts of the clam production in Nykøbing Mors. The only expense in acquiring these is the transportation from Nykøbing. The clay used for the floor and wall-plaster is also a by-product from a local gravel plant. In building his house Steen drew on well-known techniques of straw-building which he has elaborated on in his many building projects, as well as a host of other techniques he has picked up from different places. An example of this is the “Russian windows” he has recently installed. These windows feature two layers of glass, but unlike traditional double glazing the space between the plates is not a vacuum. Instead, holes facing outwards are made at every twenty centimetres allowing air to flow up the space. At the top of the window facing inwards a vent allows air to enter. As the two plates function as a solar-collector, the air is 6 heated on the way up towards the vent, leading heated air into the house while preventing the warmer air from inside escaping. During our last visit to Steen’s house on a sunny autumn day, we measured a temperature increase in the air of 10 to 23 degrees Celsius as it flowed up between the glass plates. This technique is low cost as it can be done by simply placing a new glass and frame on an existing single-layer or traditional insulation window and making holes at the bottom. According to Steen the technique was rediscovered by a group of people visiting 18th century Russian palaces. Steen’s house at Friland features other interesting systems which help him maintain very low resource consumption. One such system is a washing machine with integrated water recycling. Steen’s standard washing machine is coupled to a water filtering system consisting of clam-shells and a layer of sand in which Steen has planted willows. The used water from the washing machines is pumped into the bottom of a large plastic container. Here the water is absorbed by the clam shells before being pumped to the top of the container from where it flows down through the sand layer. This filter cleans the water through five cycles before it is re-used. The residues of soap and dirt are transformed into plant material as it is absorbed by the willows growing in the sand. The system loses water with each wash, as the clothes are still wet when being hung out to dry, but lost water is replaced with rain water. Another interesting system deployed by Steen is the on-site wastewater treatment system. Steen’s greenhouse is used not only to grow fruits and vegetables but also to treat the wastewater from the household. In his toilet Steen uses left over water from his bathtub to clean the toilet pan. The water from the toilet flows to an underground trixtank (a form of sedimentation tank, which sorts out the solid matter and allows fluids to pass) and from there to his greenhouse. The greenhouse wastewater treatment system consists of a membrane dug into a one meter deep hole. In the bottom is a layer of clam shells which can absorb a great deal of water and topped by a 20 centimetres layer of sand. The sand keeps the smell from the wastewater down and no weeds can grow in the sand. Rows of mixed clay and sand hold the plants which extract the water from the clam shell basin. It is fascinating to see the resourcefulness in the way that existing resources are reused and re-employed. The tests done conducted by researchers at the local university, as well as the Steen’s own experience, suggest that bacteria and vira as well as hormones and heavy metals do not seep into the plants. It is, however, necessary for Steen and his family to avoid certain types of such as perfume and deodorant and the use of medicines must be restricted. Finally, satisfactory functioning of the system depends on a balance between water, urine and faeces. The result, however, is interesting. Firstly, Steen takes care of his own wastewater in a closed system that does not affect the surrounding environment. He does not lead wastewater into the public system, and therefore does not have to pay wastewater fees, nor burden the public system. Secondly, he produces value in his greenhouse of 3,000 to 5,000 DKK each year. Steen’s entrepreneurial practices extend beyond his own housing. In his work as a public speaker, workshop organizer and co-builder of multiple alternative building projects Steen disseminates his knowledge, knowhow and experiences well beyond Friland. On one such occasion Steen met a group of Nepalese, who were intrigued by Steen’s approach, and saw that he might help them in re-building their native village in Nepal. According to Steen, the people live in substantial stone houses, but the houses are leaky as they have open fires in the houses. But with the extreme shifts in temperature in the area better insulation is vital for better housing. Yet, the resource base of a Nepalese village at 3000 meters above sea level is very different from what Steen has worked with in Jutland. For instance, there are no straw bales. So during his trip to Nepal Steen went searching for local materials to insulate the houses. On his many walks up and down the mountain Steen was able to find pine tree leaves that can be used as insulation instead of straw bales, bamboo to build casings for the pine tree leaves as well as clay at the bottom of the valley for clay plaster. With these materials Steen will be able to construct an insulating layer around the existing slate houses. The existing one-layer windows can be converted to Russian windows with the addition of another layer of glass. Furthermore, he will help build in-house ovens for heating and cooking. The ovens combined with improved insulation will reduce firewood use to a fourth of the current consumption and secure more stable heat levels inside the houses, as the walls and oven will now absorb and release heat much slower. Steen’s most recent project is to start a venture that will build and sell pre-fabricated straw-bale walls as modules, similar to the techniques for timber houses, where the walls and roof is pre-fabricated and collected on-site. While this project is still in the early stages Steen is convinced that this may prove a great success. 7 Forms of bricolage From the story above it is clear that Steen make systematic and extensive use of the resources at hand, what Baker and Nelson (2005) refer to as bricolage. In the following analysis the different forms of bricolage used by Steen are elaborated to increase understanding of how resource oriented entrepreneurship leads to the creation of environmentally sustainable practices and solutions. The messy appearance of Steen’s lot indicate a form of practice strongly associated with bricolage, namely scavenging (Baker & Nelson, 2005), understood as the collecting of resources that others have eschewed or do not intend to use. Steen thus has continuously collected materials and tools from a number of sources that have deemed them useless- recycling par excellence! This collection of resources provides material from which Steen can derive resources for any given new project, thus broadening his bricolage capabilities. Scavenging practices are also evident in Steen’s use of resources that are by-products or waste-products (clay and clam shells). Such practices reduce strain on the environment, as they substitute other products that would have incurred production costs, e.g. leca, (a form of clay which is extensively heat treated to provide insulation) and also makes local waste management of the waste products unnecessary and even superfluous. Putting the resources to use that have been collected through scavenging thus constitutes a form of recycling. Recycling as a form of bricolage suggests that recycling resources can be a way of making do, where resources which have already been produced and used are “at hand” in the sense that they do not have to be re-produced or re-purchased. Recycling, as practiced by Steen, where the resources to be recycled are acquired at no or low cost, represents a form of bricolage that reduces the strain placed on the natural environment as the environmental costs of production have already been incurred. Moreover, it reduces the strain on Steen’s finances. In some cases where recycled materials were not available Steen made an effort to use locally available resources, i.e. resources that are naturally available in the local setting in which the practice takes place. We saw this in Steen’s building of his house in which local timber and straw bales were used. It was also evident in Steen’s Nepalese project in which he searched the local environment to find resources that would perform similarly to straw bales, timber and clam shells in the Danish context. Disregarding potential costs of acquisition, local resources are more “at hand” than non-locally produced or available resources. Using locally available resources – ceteris paribus – reduces strain on the environment, mainly due to the transportation costs. The importance of this is particularly pertinent in the Nepalese project, in which the use of local clay will make the import of expensive cement produced in non-local factories unnecessary, thus easing the pressure on local finances and the natural environment effected by cement production and transportation. The ceteribus paribus is worth noticing in this respect, as local products can be much more expensive than non-local. This however may often be due the costs of processing raw materials into finished products. Local products may also be less environmentally friendly than non-local despite transportation. We see this for example in the production of tomatoes in Denmark or Scotland, which, if produced in a heated greenhouse may lead to more CO2 emission than Spanish tomatoes transported by truck to the Danish market. Such considerations, however, lead directly into another bricolage practice performed by Steen. This practice is the use of unprocessed materials. Straw bales, clay plaster, raw timber, pine leaves, bamboo, clam shells and so forth are resources that have not been industrially processed or refined. Such resources are “at hand” as they can be collected without the need for industrial processing. For Steen, these materials are often locally available or obtainable at a low cost, both financially and environmentally. The industrial processing and refinement of building materials is both costly and have negative environmental impacts. Steen circumvents these costs and impacts by using materials that are not industrially refined. Using raw timber instead of pressure impregnated tree, clam shells instead of leca, straw bales instead of rockwool; all these practices have a significant positive environmental impact. As Steen proudly points out, if the house is to be torn down, he can just let it decay and it will assimilate into the natural cycle leaving no damaging substances. Furthermore, according to Steen using such materials makes for a much better indoor climate. Steen also enacts a form of bricolage in his semi-closed systems, such as his washing machine recycling water or his wastewater management system. Both these systems literally use the water at hand to significantly lower the amount of water drawn from the public water system. These systems recycle and reuse “waste” water in a cycle that, although not entirely closed, reuses water within a system over which 8 Steen has a large degree of control. Indeed we note how he even reuses the “waste” to fertilise his greenhouse. Steen not only reduces his use of water, but also derives value from the system. The nutrients in the wastewater are converted into plant material from which Steen can harvest fruits and vegetables, worth some 3.000 to 5.000 DKK each year. In this context of minimalisation, this is substantial amount for Steen given that his total housing costs are around 10.000 DKK p.a.. Deriving value from such closed system constitutes a “making do”, as value is created with resources that are available and that under normal circumstances would be fed into the public wastewater management system. The above mentioned six forms of bricolage used by Steen are summarised in table 1 below. Table 1: Forms of bricolage Form of bricolage Scavenging Recycling Using local materials Using unprocessed materials Establishing semi-closed systems Extracting systems value from semi-closed Examples of use Visible from the many resources collected and stored at Steen’s lot at Friland In the water recycling systems, and multiple aspects of Steen practice In the use of straw bales, raw timber, clay at the Friland house as well as bamboo, pine leaves and clay in Nepal Same as above In the wastewater systems reusing the grey water from the household and the recycling of water from the washing machine In the growing of vegetables and fruits in the green house which uses the grey water Entrepreneurship as re-sourcing Our analysis of Steen Møller and his various form of bricolage demonstrate that resource oriented environmentally sustainable entrepreneurship exists as an empirical phenomenon with certain definite characteristics and positive effects. Indeed it signals that resources are perhaps the most important element in the pursuit of the contribution of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurs in the pursuit of sustainability. Indeed resource is defined as both “a stock or supply of money, materials, staff, and other assets” and “an action or strategy which may be adopted in adverse circumstances” (Oxforddictionaries.com). Both the former and latter are exemplified in Steen’s resourcefulness. Moreover it can be seen as innovative, a Schumpeterian recombination; but one where the focus is on recombining resources at hand. We thus propose that sustainable entrepreneurship can be seen as “re-sourcing”. This type of entrepreneurial action differs from traditional opportunity and market oriented entrepreneurship in a number of ways. It re-sources by seeking out resources in another way. Instead of looking for the best bargain in the market, and acquiring resources for the immediate goal pursued, re-sourcing seeks and accumulates resources “at hand”. “At hand” here understood in a somewhat broader sense than suggested by Baker and Nelson and includes local and unprocessed materials. It re-sources by seeking a broader range of ends in the combination of and value creation from resources. Economic profit is of a secondary importance. Instead social, personal, community, societal and environmental value is sought first and foremost (Korsgaard & Anderson, forthcoming; Steyaert & Katz, 2004). It seeks to realise “appreciate ways of living that are simple in means but, but rich in ends” (Sachs, 1999, p. xi). Discussion and limitations The study presented above contributes to our understanding of sustainable entrepreneurship in a number of ways. It is however not without its limitations and we discuss two of these limitations. 9 Firstly, the ceteris paribus, of Steen’s practices are worth going into some detail. The six forms of bricolage practiced by Steen are – ceteris paribus – likely to be more sustainable than other forms of entrepreneurial practices. Yet, this holds true only if the resources used can be stored and used without being directly environmentally harmful. As an example, scavenging is sustainable only if the resources scavenged and stored do not lead to the emission of toxic or otherwise harmful substances. For instance it may well be the case that the scavenging of old oil tanks is not a sustainable practice. The same is the case for recycling, which is sustainable if the potential environmental damages offset those caused by the production and use of a newer alternative. Baker and Nelson (2005) cite three examples of bricolage that has harmful environmental consequences, and where new resources – from an environmental perspective – should have been acquired. It can therefore not be said that all forms of resource oriented entrepreneurial actions are environmentally sustainable. (Although some scholars suggest that they are more economically sustainable (Sarasvathy, 2001, 2008)). Yet, it seems that there is vast potential in the use of resource oriented entrepreneurial action, if this is coupled with an awareness and interest in environmental sustainability, such as we find it with Steen Møller. It could thus be argued, that informing about and teaching bricolage skills in combination with sustainability issues would be highly valuable in all forms of higher education, including science, social science and humanities. Secondly, a single case study, as presented in this paper, suffers from limitations in terms of generalisation (Yin, 2009). Such a case study cannot be said to be exhaustive of the phenomenon nor can the practices of Steen Møller be claimed to be representative for all resource oriented sustainable entrepreneurs (Yin, 2009). Yet, we suggest that the actions of Steen Møller are valuable for a number of reasons. The overall impact of Steen Møller cannot be measured solely by the sustainability level of his household. Steen also acts as a role model and source of inspiration for others. The Friland community in which he resides, is largely built on principles formulated by Steen. The Friland project has been given substantial public attention, and to some extent helped set an agenda concerning sustainability. In terms of inspiring others Steen’s most valuable contribution to sustainability is providing a response to two key challenges in terms of sustainable resource consumption: (i) making visible the flow of resources such as water and electricity and (ii) anchoring these flows locally (Heidenreich, 2009).2 Steen accomplished both tasks. As his house is built from local and unprocessed materials they can unproblematically re-enter the local natural cycle as the clam shells, straw bales, timber and clay plaster will decay without leaving harmful substances. Another example is the wastewater management system which is locally anchored and very effectively makes visible the flow of the resources. So by communicating his practices into the public Steen makes the flows visible heightening the awareness of the environmental challenges. The case study of Steen Møller thus provides insights into the phenomenon as well as learning points for both academics and practitioners. References Aldrich, H. E. & Fiol, C. M. 1994. Fools Rush in - the Institutional Context of Industry Creation. Academy of Management Review, 19(4): 645-670. Anderson, A. R. 1998. Cultivating the Garden of Eden: environmental entrepreneuring. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 11(2): 135-144. Anderson, A. R. & McAuley, A. 1999. Marketing landscapes: The social context. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 2(3): 176-188. Archer, G. R., Baker, T., & Mauer, R. 2009. Towards an alternative theory of entrepreneurial success: Integrating bricolage, effectuation and improvisation, Babson College Entrepreneurship Research Conference. Babson Part, MA. Heidenreich suggest that “The specific and widespread blindness that characterizes current cultural perception of modern, technically mediated exchanges with nature is one of the greatest obstacles to sustainable development” and that “it is necessary to decentralize the centralized spaces of flow, to organize them, as far as possible, at a local or regional level. Local and regional responsibility for natural resources brings them closer to communities, local councils, common affairs, and civil society. Local water- and renewable energy sources must be explored and sensibly exploited. In this process, water, and energy supply of communities will become more perceivable.” 2 10 Baker, T., Miner, A. S., & Eesley, D. T. 2003. Improvising firms: Bricolage, account giving and improvisational competencies in the founding process. Research Policy, 32(2): 255-276. Baker, T. & Nelson, R. E. 2005. Creating Something from Nothing: Resource Construction through Entrepreneurial Bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3): 329-366. Baker, T. 2007. Resources in play: Bricolage in the Toy Store(y). Journal of Business Venturing, 22(5): 694711. Berglund, H. 2009. Austrian economics and the study of entrepreneurship: concepts and contributions, Academy of Management Conference. Chicago, Ill. Chiles, T. H., Bluedorn, A. C., & Gupta, V. K. 2007. Beyond Creative Destruction and Entrepreneurial Discovery: A Radical Austrian Approach to Entrepreneurship. Organization Studies, 28(4): 467-493. Cohen, B. & Winn, M. I. 2007. Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(1): 29-49. Dean, T. J. & McMullen, J. S. 2007. Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(1): 50-76. Dorado, S. 2006. Social Entrepreneurial Ventures: Different Values so Different Process, No? Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 11(4): 319-343. Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989. Building Theories From Case Study Research. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4): 532-551. Flyvbjerg, B. 2004. Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research. In C. Seale & G. Gobo & J. F. Gubrium & D. Silverman (Eds.), Qualitative Research Practice: 420-434. London: Sage. Garud, R. & Karnøe, P. 2003. Bricolage versus Breakthrough: Distributed and Embedded Agency in Technology Entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 32(2): 277-300. Gerlach, A. 2003. Sustainable entrepreneurship and innovation. Paper presented at the Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, Leeds. Harbi, S. E., Anderson, A. R., & Ammar, S. H. 2010. Entrepreneurs and the environment: towards a typology of Tunisian ecopreneurs. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 10(2): 181-204. Hayek, F. A. 1945. The Use of Knowledge in Society. The American Economic Review, 35(4): 519-530. Heidenreich, E. 2009. Spaces of flow as technical and cultural mediators between society and nature. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 11(6): 1145-1154. Jack, S. L. & Anderson, A. R. 2002. The effects of embeddedness on the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(5): 467-487. Kirzner, I. M. 1973. Competition and Entrepreneurship. Chicago, Ill.: The University of Chicago Press. Klein, P. G. 2008. Opportunity Discovery, Entrepreneurial Action, and Economic Organization. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 2(3): 175-190. Korsgaard, S. 2009. Essays on entrepreneurial opportunities. Aarhus Business School, University of Aarhus, Aarhus. Korsgaard, S., Berglund, H., Thrane, C., & Blenker, P. 2010. A tale of two Kirzners: Time, uncertainty and the 'nature' of opportunities, 16th Nordic Conference on Small Business Research. Kolding, Denmark. Korsgaard, S. & Anderson, A. R. forthcoming. Enacting entrepreneurship as social value creation. International Small Business Journal. Krueger, N. J. 1998. Encouraging the identification of environmental opportunities. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 11(2): 174-183. Kuckertz, A. & Wagner, M. forthcoming. The influence of sustainability orientation on entrepreneurial intentions -- Investigating the role of business experience. Journal of Business Venturing, In Press, Corrected Proof. Mackelworth, P. & Carić, H. forthcoming. Gatekeepers of island communities: exploring the pillars of sustainable development. Environment, Development and Sustainability, In press. Mitchell, R. K., Busenitz, L., Lant, T., McDougall, P. P., Morse, E. A., & Smith, J. B. 2004. The Distinctive and Inclusive Domain of Entrepreneurial Cognition Research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(6): 505518. Nath, B., Hens, L., & Pimentel, D. 1999. Editorial. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 1(1): 1-2. Oxforddictionaries.com. Pacheco, D. F., Dean, T. J., & Payne, D. S. forthcoming. Escaping the green prison: Entrepreneurship and the creation of opportunities for sustainable development. Journal of Business Venturing, In Press, Corrected Proof. Phillips, N. & Tracey, P. 2007. Opportunity recognition, entrepreneurial capabilities and bricolage: connecting institutional theory and entrepreneurship in strategic organization. Strategic Organization, 5(3): 313-320. Sachs, W. 1999. Planet dialectics: Explorations in envrionment and development. London: Zed Books. 11 Sarasvathy, S. D. 2001. Causation and Effectuation: Toward a Theoretical Shift from Economic Inevitability to Entrepreneurial Contingency. Academy of Management Review, 26(2): 243-264. Sarasvathy, S. D. 2008. Effectuation: Elements of Entrepreneurial Expertise. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Schaper, M. 2002. The Essence of Ecopreneurship. Greener Management International, 38: 26-30. Shane, S. & Venkataraman, S. 2000. The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1): 217-226. Stake, R. E. 2000. Case Studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.: 435-454. London: Sage. Stevenson, H. H. & Jarillo, J. C. 1990. A Paradigm of Entrepreneurship - Entrepreneurial Management. Strategic Management Journal, 11: 17-27. Steyaert, C. & Katz, J. 2004. Reclaiming the space of entrepreneurship in society: geographical, discursive and social dimensions. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 16(3): 179-196. Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. 1990. Grounded Theory Methodology: An Overview. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research: 273-285. Thousand Oaks, CA.: Sage. Venkataraman, S. 1997. The Distinctive Domain of Entrepreneurship Research: An Editor's Perspective. In J. Katz & R. Brockhaus (Eds.), Advances in Entrepreneurship, Vol. 3: 119-138. Greenwich: JAI Press. World Commission on Environment, D.; Our Common Future; 16 December, 2009. Yin, R. K. 2009. Case Study Research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. York, J. G. & Venkataraman, S. forthcoming. The entrepreneur-environment nexus: Uncertainty, innovation, and allocation. Journal of Business Venturing, In Press, Corrected Proof. 12