Nici Huval Huval 1 Mrs. Huval English II (H)

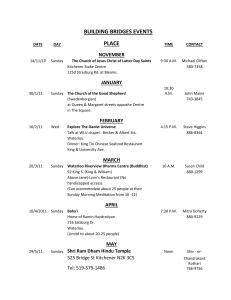

advertisement

Nici Huval Huval 1 Mrs. Huval English II (H) -3 31 March 2014 U2 and Ireland’s “Troubles” U2, one of Ireland’s most famous exports, regaled rock fans in the 1980s with anthems such as “In the Name of Love (Trust),” and “With or Without You.” The epitome of “cool,” Bono, The Edge, Larry Mullen and Adam Clayton, traveled the world packing stadiums, making videos and causing teenaged girls to swoon, but their songs also matter and reflect their love of their homeland and their desire for peace in it. No other U2 song means more than “Sunday, Bloody Sunday,” a song which laments the conflict between Catholics in Northern Ireland and their unionist Protestant foes, known in Ireland as “The Troubles.” Ireland’s unrest began centuries ago, as throughout history the island nation has fought off foreign invasions, most recently from the British. The modern version of these problems, dubbed “The Troubles” occurred in Northern Ireland between the “unionist” Protestant group and the “nationalist” Catholic group, according to “The Troubles” by The BBC ( ). The Protestants unionists wanted Northern Ireland to remain a part of Great Britain, whereas, the Catholic nationalists wanted Northern Ireland to unify with The Republic of Ireland. Since that time, rebel groups in Northern Ireland have resisted British occupation in various ways, mostly violent, constituting what would now qualify as terrorism. That, combined with the often extreme response of the British troops, according to ________________ in the Huffington Post, comprised Huval 2 “The Troubles” ( ). Prior to Bloody Sunday, violence and acrimony increased between the Protestant unionists and the Catholic nationalists. Riots in the streets, bombings by both sides, strikes by workers protesting army tactics, and ultimately the British decision to “inter” instigators, or imprison them without trial, combined to create an extremely volatile situation. As ________ Paul explains in his article “____________,” “On the weekend before Bloody Sunday, a protest was held outside an internment camp. It led to a clash between paratroopers and protestors…it served as a mild rehearsal for Bloody Sunday” ( ). The “Bloody Sunday,” about which Bono and company sing, actually occurred on January 30, 1972. Chris Weigant of the ____________ explains that on this date, a civil rights march was underway in Bogside, which is in Derry, Northern Ireland. During the march, the British military forces occupying the area opened fire on those gathered, killing thirteen protesters, none of whom were carrying weapons, and injuring thirteen more ( ). In the words of U2’s lead singer, Bono, “It was a day that caused the conflict between the two communities in Northern Ireland – Catholic nationalist and Protestant unionist – to spiral into another dimension: every Irish person conscious on that day has a mental picture of Edward Dale, later the bishop of Derry, holding a bloodstained handkerchief aloft as he valiantly tended to the wounded and the dying” ( ). Bono believes that the attack, seemingly unwarranted, and the bloody results resonated with citizen of Northern Island and escalated the conflict and the violence. The results were undeniable. After Bloody Sunday the British Embassy in The Republic of Ireland’s capital Dublin was burned completely while the funerals of the victims, Huval 3 publicized extensively, overflowed with important dignitaries from local Irish government and the Catholic Church. There followed years of extensive bombings and streetfighting mixed with attempts by both governments to achieve peace ( ). All in all, “The Troubles” cost the lives of 3,700, according to The Economist article “_____________________________________.” Of those 3,700 lives lost, an estimated 1,800 died at the hands of the IRA, the Catholic, Northern Ireland nationalist group, the Irish Republican Army. About 1000 more died at the hands of what The Economist dubs, “Extreme Protestant groups” ( ). While 250,000 troops worked in Northern Ireland during this time, only 300 lives were taken by these soldiers ( ). The events leading up to Bloody Sunday, the tragic deaths on that January day, and the violent aftermath all seemed to converge in 1982 in the mind of the band members as they composed “Sunday, Bloody Sunday.” The conflict still raged on, and the death toll climbed. In the song, the lyrics ask how long the song will be sung, lamenting the violence between the two sides, and expressing the hope that Ireland can be one nation at peace. The song features strong imagery. In the first verse, the band writes, “Broken bottles under children’s feet / Bodies strewn across the dead-end street” ( ). The fact that the broken glass seems to endanger the children contrasts with the image of the dead littering the pavement on a street that leads nowhere, just as the conflict seems to be leading Ireland nowhere. The song also features war imagery through the implied metaphor of Irish hearts as battlefields. The second verse continues, “The trenches dug within our hearts / And mothers, children, brothers, sisters / Torn apart” ( ). Here, the hearts of the Irish are divided with trenches, commonly Huval 4 used in World War I. The trenches separate families, just as “The Troubles” divide the Irish population. The band also criticizes the world watching the crisis, but not doing enough to stop it: “And it’s true we are immune/ When fact is fiction and TV reality. / And today the millions cry /We eat and drink while tomorrow they die” ( ). These lyrics imply that the media may not present the truth of events in Ireland to the public, and in addition, viewers seldom look deeper, preferring to mindlessly believe what the media contends. Initially, when the song was first written in 1982, U2 feared that a song like “Sunday, Bloody Sunday” would increase violence in Ireland. As Bono said in a live performance in 1982, “For a long time I have been frightened …about writing a song about where I live…Ireland and its problems…this is not a rebel song” ( ). He clearly doesn’t want either side to interpret his song as a call for more violence. In fact, for some time U2 omitted “Sunday, Bloody Sunday” from its set list. In Northern Ireland, U2 performed this song only two times since the song’s inception ( ). Today, however, the song has reclaimed its spot in the band’s live performances as one of U2’s most popular songs. Since the 1980s, relations between the Irish and the British have improved through peace talks and diplomacy; “The Troubles” seem to have been laid to rest. In 2010, the British Government released The Saville Inquiry ( ). The inquiry represented over eight years of investigation and hearings into the events of Bloody Sunday on the part of the British Government. Ultimately, the British government apologized for the deaths of the protesters and laid blame squarely on the Huval 5 shoulders of the British soldiers who killed thirteen people that day. The report called the shots “unjustified firings” and found that, “...the British soldiers ‘lost control’ and shot civilians in the back who were trying to escape” ( ). The legacy of “The Troubles” and the song, “Sunday, Bloody Sunday,” seem intertwined, and also serve as inspiration to other people fighting injustice and enduring civil strife. As Bono concludes in a Rolling Stone article, “The song will be sung wherever there are rock fans with mullets and rage, from Sarajevo to Tehran” ( ). Huval 6 Works Cited Arthur, Paul. "Bloody Sunday." Encyclopedia of Irish History and Culture. Ed. James S. Donnelly, Jr. Vol. 1. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. 51-52. World History in Context. Web. 28 Mar. 2014 Bono, The Edge, Larry Mullen and Adam Clayton. "Sunday Bloody Sunday." U2.com. U2 and Live Nation Entertainment, 2014. Web. 25 Mar. 2014. Kreps, Daniel. "Bono Remembers the Real "Bloody Sunday"" Rolling Stone. Jann S. Wenner Publishing, 22 June 2010. Web. 25 Mar. 2014. "Long Time Coming; The Bloody Sunday Inquiry." The Economist 19 June 2010: 61(US). World History in Context. Web. 28 Mar. 2014. "The Troubles: Thrity Years of Conflict from 1968-1998." BBC News. BBC, 2014. Web. 01 May 2014. Weigant, Chris. "Sunday Bloody Sunday." The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 16 June 2010. Web. 25 Mar. 2014.