Slide - WordPress.com

NIKOLAOS BOGIATZIS

Slide

An image can be seen in a lot of ways. It can give information of that which is shown or be used as memorabilia of a past period. The image of The

Holden Gallery - as it is called nowadays - is part of this slide that I have in front of me. The Holden Gallery is a place that I visit very often and I am familiar with. However, it looks different in this image taken by a photographer circa 1900. The presence of the people of a past era makes the image more distant from the present. Hans Belting wrote that ‘ images both affect and reflect the changing course of human history ‘ (Belting, 2011, p. 10).

Moreover, they reflect the changes in places.

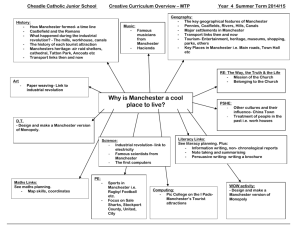

The image that I am trying to see is in a plastic frame. A black and white photograph, surrounded by a grey plastic frame. Two stickers with letters and numbers written with a black and red pen, and a grey circle complete the identity of this slide ( Fig. 1 ).

( Fig. 1 )

I touch it. It is a lightweight object. As I touch it, another image, that of my

View-Master invades my mind. I used it as a child. Through this slide of a

Mancunian place, my mind travels to a Thessalonian childhood memory, back in Greece.

The familiar landmarks of my thought - our thought, the thought that bears the stamp of our age and our geography - breaking up all the ordered surfaces and all the planes with which we are accustomed to tame the wild profusion of existing things, wrote Foucault in 1966 ( DuBois, 2009, p. 93 ).

The slide shows nine people who interacted with works of art, objects which are the protagonists of the image. Those people were in the Textile Court - that was the name of the place then - because of art. I frequently visit the same place which now has a different name, The Holden Gallery, for the same reason. The sight of the slide causes a feeling of continuity. This is one of the

object’s functions : ‘ To ensure the continuity of life ‘, highlighted Baudrillard in 1996 (Baudrillard, 2009, p. 55).

The image is in a good condition. However, there are some evident traces of time upon it. The slide was used many times as some scratches on its plastic frame indicate. It was and still is a functional object. It was being projected in the past, as some academics used it for their lectures. It still exists as a reminder of how an area of Manchester’s School of Art looked like. But I mentioned before, I am not looking, I am trying to see. ‘ “I see” can also mean “I understand” ‘ ( Hustvedt, 2012, p. 231 ). So far, I understand that the image serves as an object of memory. This is part of another object, the slide, whose existence connects the past with the present. Barthes in 1977 wrote that the ‘there-then becomes the here-now‘ ( Edwards, 2009, p. 336 ) and believed that objects with a meaning will become speech. The slide can provide a speech through its utility and materiality. It can give some information for the period that the image was taken and if placed near some other slides, it can narrate the story of this area of Manchester’s School of

Art. However, it can narrate a different story if it will be placed in a different succession, with different slides. The same object can narrate many stories.

One can pick the story that is more familiar with or that is more utilitarian in his or her interests. ‘ One might say that in a debate about the history of an object to focus on judgemental conclusions is beside the point ‘ ( Parigoris,

1997, p. 133 ). To see the slide through its context would prove more useful, instead.

The slide is placed in a room where The Visual Resources Centre is situated.

The Centre used to be called The Slide Gallery until 2004. It was and still is a gallery full of slides. Objects that were useful to the staff and the students.

The invasion of the digital media somehow made them marginal objects.

Baudrillard wrote about the marginal objects that : ‘They appear to run counter to the requirements of functional calculation, and answer to other kinds of demands such as witness, memory, nostalgia or escapism’ (Baudrillard,

2009, p. 41). When I first entered the room, I felt like entering a spiritual venue. However, the realisation of the utility of a slide even these days eliminates this experience. The object of my research is placed alongside other objects that show images of the School of Art. The place has changed over the years. The slides gathered in the cabinet in front of me prove that. For

Aristotle, the most powerful sign of proof was the necessary one, the

tekmerion ( Nelson, 2000, p. 422 ). Each one of the slides in the cabinet can be used as tekmerion.

The Visual Resources Centre is inside the School of Art. These images showing the place through the years are held all together in the same room, as part of the slides. They are objects inside other objects. It is very important that they are placed together. In this way the institution possess them. Hans

Belting writes : ‘ One might say images resemble nomads ‘ ( Belting, 2011, p.21 ). By keeping them together, the School of Art secures the collective memory and The Visual Resources Centre becomes the subject, that is the

keeper. Its curator, added written information to the slides’ plastic frame. The usage of informative text verifies the uniqueness of the object. It distinguishes it from the others. What proves the nomadic nature of the image and of the object as well, is that it can survive in another context. I move the slide from its cabinet and I place it in a slide projector ( Fig. 2 ).

( Fig. 2 )

My object is being put into another object. The slide’s image is being projected on a third object, the projection screen. The objects’ materiality interacts and the outcome, the projection, is not material. I am thinking of

Benjamin’s words in 1936 :

The authenticity of a thing is the essence of all that is transmissible from its beginning, ranging from its substantive duration to its testimony to the history which has experienced. Since the historical testimony rests on the

authenticity, the former, too, is jeopardized by reproduction when substantive duration ceases to matter. And what is really jeopardized when the historical testimony is affected is the authority of the object (Benjamin, 1992, p. 514).

The curator of The Visual Resources Centre categorised the slide and he preserves it. Academics used it in their teachings. I am using it as an object of research and as a link with the history of Manchester School of Art. The slide is present. Its materiality is present, as well. The way that the slide is treated can either make it marginal or not. This depends on a person’s perspective on an object and even on his social views. ‘ Under capitalism,

Marx suggested, the simple useful object becomes a performer ‘ (Henning,

2009, p. 458). How the slide will be treated, depends on the person that will handle it. How an object is approached, depends on the knowledge of the person that handles the object . The biography of the object is a useful source of knowledge.

Lantern slides appeared in 1849. Photography acquired new potential as photographs then could be seen by a bigger audience and used for entertainment and educational purposes, as well ( The Library of Congress,

2015 ). The slide that I am looking at, has the letters ‘ M C A D ‘ written upon its sticker. This means that it was made before 1970, when the

Manchester School of Art was named Manchester College of Art and Design.

However, the image of the slide is older. It shows a part of The Arts and

Crafts Museum of the Manchester Municipal School of Art, that is the Textile

Court. ‘ The School museum was officially opened on the 28 October 1898 under its first curator, Miss May C. Fisher, and for the first time there was adequate exhibition space to display the ( School’s ) collection ‘ ( Jeremiah,

1980, p. 30 ). The photograph was taken in the early 1900s by E. M. Chapman.

It includes ‘ the William Morris tapestry on the centre wall, textiles from the

“Book Collections”, Greek Vases from the Palgrave Collection ( loaned by the

City Art Gallery ), together with purchases from the arts and crafts exhibition and stained glass cartoons by F. W. Shields, E. Burne-Jones and Ford Maddox

Brown ‘ ( Jeremiah, 1980, p. 15 ). All these works of art are objects. And in this image of my object which is the slide, I have the ability to know more about how a part of The Arts and Crafts Museum looked like. This makes me want to find out how The Arts and Crafts movement linked with the museum.

In 1880 the School was based on Cavendish Street and the chairman was

Charles Rowley ( Fig. 3 ).

( Fig. 3 )

He was a friend with William Morris, a socialist as well, and through Morris he met many notable people from the Arts and Crafts movement. One of them was Walter Crane ( Fig. 4 ).

( Fig. 4 )

Rowley wanted to introduce the ideas of the movement into the School through Crane’s involvement. From 1893 until 1896, Crane was the Director of

Design. His influence in the School continued even after his resignation ( Davis,

1994, pp. 13 - 14 ). The collection of Arts and Crafts works was begun when

Crane was the Director. He believed that museums could play a significant part to education. However, it was Rowley who influenced the collection’s content. With the decline of the Arts and Crafts movement, the nature of the museum and its space changed ( Davis, 1994, pp. 14 - 19 ).

The slide was an object that was part of a narrative. In the past when lectures were given with the use of slides, not through Powerpoint, a lecturer would use it as a historical tekmerion. Many would see it as a marginal object nowadays. I doubt it. Through the slide I am looking, I see the changes of an institution. I realise the importance of the individual factor in the way that culture and education is given. It all started when the object was put out of its cabinet. If someone would not move the object, it would be a part of a mythology. The mythology of the antique. However, the slide became

functional and ‘ the functional object is efficient ‘ ( Baudrillard, 2009, p. 42 ).

Even now, in the digital epoch, the slide survives in a competitive way. It intrudes my laptop’s keyboard in a nomadic sense. It is here to narrate a story, interact with me and with the other readers of my text. Nelson writes :

‘ If slides are tangible enough objects, and speakers and audiences readily recognisable subjects, their mutual interaction yields what Bruno Latour calls

“quasi-objects” and “quasi-subjects” ‘ ( Nelson, 2000, p. 415 ). The slide can be an object of knowledge and memory, personal and collective. It is available and waits to be explored.

In conclusion, the slide is an object. It contains an image, which is an object by itself. The image shows some works of art, objects of the past which help me understand more about the institution that I am based in, and in which I interact with others. The slide makes me reflect on the history of the place and even brings to my mind images of my life in the past. Through its materiality, comes its functionality. ‘ Every object has two functions - to be put to use and to be possessed ‘ ( Baudrillard, 2009, p. 48 ). It is the same object but it can tell many stories through its ability to be placed within various contexts. Once it will be put out of its cabinet, it can serve as a

tekmerion. It can be put into another object, the slide projector and through a third object which is the projection screen, its narrative will start. The process of projection is not material. However, the nature of the slide is nomadic. It has the ability to survive and through its function of narration it can prove its efficiency. It interacts with different subjects. ‘ Together they create narratives and social bonds and transform shadows into art, monument, symbolic capital, or disciplinary data ‘ ( Nelson, 2000, p. 415 ).

References

Baudrillard, J. ( 2009 ) ‘ Subjective Discourse or the Non-Functional System of

Objects ‘ In Candlin, F., Guins, R. ( eds. ) The Object Reader. Oxon , New

York : Routledge, pp. 41 - 63.

Belting, H. ( 2011 ) An Anthropology of Images : Picture, Medium, Body.

Princeton, N. J. : Princeton University Press.

Benjamin, W. ( 1992 ) ‘ The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical

Reproduction ‘ In Harrisson, C. , Wood, P. ( eds.) Art in Theory, 1900 - 1990 :

An Anthology of Changing Ideas. New Jersey : Blackwell, pp. 512 - 520.

Davis, J. ( 1994 ) ‘ An Arts and Crafts Education ‘ In Shrigley, R. ( ed. )

Inspired by Design : The Arts and Crafts Collection of the Manchester

Metropolitan University. Manchester : Manchester City Art Galleries & MMU, pp. 9 - 20.

DuBois, P. ( 2009 ) ‘ Dildos ‘ In Candlin, F., Guins, R. ( eds. ) The Object

Reader. Oxon , New York : Routledge, pp. 92 - 109.

Edwards, E. ( 2009 ) ‘ Photographs as Objects of Memory ‘ In Candlin, F.,

Guins, R. ( eds. ) The Object Reader. Oxon , New York : Routledge, pp. 331 -

342.

Henning, M. ( 2009 ) ‘ The Cosmic Symbol ‘ In Candlin, F., Guins, R. ( eds. )

The Object Reader. Oxon , New York : Routledge, pp. 456 - 458.

Hustvedt, S. ( 2012 ) ‘ Notes on Seeing ‘ In Hustvedt, S. ( ed. ) Living,

Thinking, Looking. London : Sceptre, pp. 223 - 231.

Jeremiah, D. ( 1980 ) A Hundred Years and More. Manchester : Manchester

Polytechnic.

Nelson, R. S. ( 2000 ) ‘ The Slide Lecture, or the Work of Art "History" in the

Age of Mechanical Reproduction ‘, Critical Inquiry, 26 ( 3 ), pp. 414 - 434.

Parigoris, A. ( 1997 ) ‘ Truth to Material : Bronze, on the Reproducibility of

Truth ‘ In Hughes, A., Ranfft, E. ( eds. ) Sculpture and its Reproductions.

London : Reaction, pp. 131 - 151.

The Library of Congress Lantern Slides : History & Manufacture [ online ]

[Accessed on 13 February 2015] http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/landscape/lanternhistory.html

Bibliography

Candlin, F., Guins, R. ( 2009 ) The Object Reader. Oxon , New York :

Routledge.

Illustration list

( Fig. 1 ) : Davis, J. ( 2015 ) Slide, Digital photograph, MMU Visual Resources

Centre, Manchester.

( Fig. 2 ) : Davis, J. ( 2015 ) Projection, Digital photograph, MMU Visual

Resources Centre, Manchester.

( Fig. 3 ) : Brown, Ford Madox ( 1885 ) Charles Rowley, Oil on canvas, http://victorianweb.org/painting/fmb/paintings/22.html

( Fig. 4 ) : Watts, G. F. ( 1891 ) Walter Crane, Oil on canvas, http://www.wikiart.org/en/george-frederick-watts/walter-crane