William H. Sewell (0101), Transcript

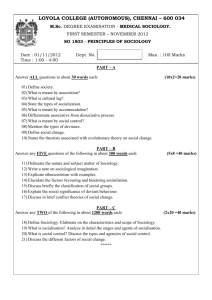

advertisement