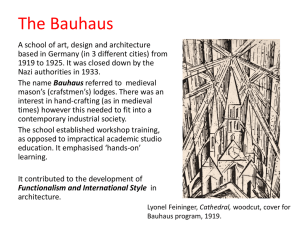

About Bauhaus Movement

advertisement

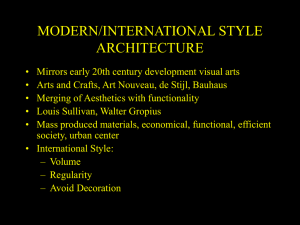

Alexandra Griffith Winton Independent Scholar The Bauhaus was founded in 1919 in the city of Weimar by German architect Walter Gropius (1883–1969). Its core objective was a radical concept: to reimagine the material world to reflect the unity of all the arts. Gropius explained this vision for a union of art and design in the Proclamation of the Bauhaus (1919), which described a utopian craft guild combining architecture, sculpture, and painting into a single creative expression. Gropius developed a craft-based curriculum that would turn out artisans and designers capable of creating useful and beautiful objects appropriate to this new system of living. The Bauhaus combined elements of both fine arts and design education. The curriculum commenced with a preliminary course that immersed the students, who came from a diverse range of social and educational backgrounds, in the study of materials, color theory, and formal relationships in preparation for more specialized studies. This preliminary course was often taught by visual artists, including Paul Klee (1987.455.16), Vasily Kandinsky (1866–1944), and Josef Albers (59.160), among others. Following their immersion in Bauhaus theory, students entered specialized workshops, which included metalworking, cabinetmaking, weaving, pottery, typography, and wall painting. Although Gropius' initial aim was a unification of the arts through craft, aspects of this approach proved financially impractical. While maintaining the emphasis on craft, he repositioned the goals of the Bauhaus in 1923, stressing the importance of designing for mass production. It was at this time that the school adopted the slogan "Art into Industry." _ In 1925, the Bauhaus moved from Weimar to Dessau, where Gropius designed a new building to house the school. This building contained many features that later became hallmarks of modernist architecture, including steel-frame construction, a glass curtain wall, and an asymmetrical, pinwheel plan, throughout which Gropius distributed studio, classroom, and administrative space for maximum efficiency and spatial logic. _ _ The cabinetmaking workshop was one of the most popular at the Bauhaus. Under the direction of Marcel Breuer (1983.366) from 1924 to 1928, this studio reconceived the very essence of furniture, often seeking to dematerialize conventional forms such as chairs to their minimal existence. Breuer theorized that eventually chairs would become obsolete, replaced by supportive columns or air. Inspired by the extruded steel tubes of his bicycle, he experimented with metal furniture, ultimately creating lightweight, mass-producible metal chairs. Some of these chairs were deployed in the theater of the Dessau building. _ _ The textile workshop, especially under the direction of designer and weaver Gunta Stölzl (1897–1983), created abstract textiles suitable for use in Bauhaus environments. Students studied color theory and design as well as the technical aspects of weaving. Stölzl encouraged experimentation with unorthodox materials, including cellophane, fiberglass, and metal. Fabrics from the weaving workshop were commercially successful, providing vital and much needed funds to the Bauhaus. The studio's textiles, along with architectural wall painting, adorned the interiors of Bauhaus buildings, providing polychromatic yet abstract visual interest to these somewhat severe spaces. While the weaving studio was primarily comprised of women, this was in part due to the fact that they were discouraged from participating in other areas. The workshop trained a number of prominent textile artists, including Anni Albers (1899–1994), who continued to create and write about modernist textiles throughout her life. _ _ Metalworking was another popular workshop at the Bauhaus and, along with the cabinetmaking studio, was the most successful in developing design prototypes for mass production. In this studio, designers such as Marianne Brandt (2000.63a-c), Wilhelm Wagenfeld (1986.412.1-16), and Christian Dell (1893–1974) created beautiful, modern items such as lighting fixtures and tableware. Occasionally, these objects were used in the Bauhaus campus itself; light fixtures designed in the metalwork shop illuminated the Bauhaus building and some faculty housing. Brandt was the first woman to attend the metalworking studio, and replaced László Moholy-Nagy (1987.1100.158) as studio director in 1928. Many of her designs became iconic expressions of the Bauhaus aesthetic. Her sculptural and geometric silver and ebony teapot (2000.63a-c), while never mass-produced, reflects both the influence of her mentor, Moholy-Nagy, and the Bauhaus emphasis on industrial forms. It was designed with careful attention to functionality and ease of use, from the nondrip spout to the heat-resistant ebony handle. _ _ The typography workshop, while not initially a priority of the Bauhaus, became increasingly important under figures like Moholy-Nagy and the graphic designer Herbert Bayer (2001.392). At the Bauhaus, typography was conceived as both an empirical means of communication and an artistic expression, with visual clarity stressed above all. Concurrently, typography became increasingly connected to corporate identity and advertising. The promotional materials prepared for the Bauhaus at the workshop, with their use of sans serif typefaces and the incorporation of photography as a key graphic element, served as visual symbols of the avant-garde institution. _ _ Gropius stepped down as director of the Bauhaus in 1928, succeeded by the architect Hannes Meyer (1889–1954). Meyer maintained the emphasis on mass-producible design and eliminated parts of the curriculum he felt were overly formalist in nature. Additionally, he stressed the social function of architecture and design, favoring concern for the public good rather than private luxury. Advertising and photography continued to gain prominence under his leadership. _ _ Under pressure from an increasingly right-wing municipal government, Meyer resigned as director of the Bauhaus in 1930. He was replaced by architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1980.351). Mies once again reconfigured the curriculum, with an increased emphasis on architecture. Lily Reich (1885–1947), who collaborated with Mies on a number of his private commissions, assumed control of the new interior design department. Other departments included weaving, photography, the fine arts, and building. The increasingly unstable political situation in Germany, combined with the perilous financial condition of the Bauhaus, caused Mies to relocate the school to Berlin in 1930, where it operated on a reduced scale. He ultimately shuttered the Bauhaus in 1933. _ _ During the turbulent and often dangerous years of World War II, many of the key figures of the Bauhaus emigrated to the United States, where their work and their teaching philosophies influenced generations of young architects and designers. Marcel Breuer and Joseph Albers taught at Yale, Walter Gropius went to Harvard, and Moholy-Nagy established the New Bauhaus in Chicago in 1937. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/bauh/hd_bauh.htm The Bauhaus was a school whose approach to design and the combination of fine art and arts and crafts proved to be a major influence on the development of graphic design as well as much of 20th century modern art. Founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar, Germany in 1919, the school moved to Dessau in 1924 and then was forced to close its doors, under pressure from the Nazi political party, in 1933. The school favored simplified forms, rationality, functionality and the idea that mass production could live in harmony with the artistic spirit of individuality. Along with Gropius, and many other artists and teachers, both Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Herbert Bayer made significant contributions to the development of graphic design. Among its many contributions to the development of design, the Bauhaus taught typography as part of its curriculum and was instrumental in the development of sans-serif typography, which they favored for its simplified geometric forms and as an alternative to the heavily ornate German standard of blackletter typography. http://www.designishistory.com/1920/the-bauhaus/ http://www.fastcodesign.com/1672693/watch-the-history-of-the-bauhaus-in2-minutes#6 / images describe Among the first of design schools, The Bauhaus was focused on subjects including architecture, industrial design, graphic design, fine art, photography and new media, and became the centre of one of the most influential movements of design history. The school was first opened in 1919 by architect Walter Gropius, and over the years existed in three different German cities: Weimar (1919-1925), Dessau (1925-1932) and Berlin (1932-1933). The Bauhaus was unique at the time because it asked how the 'modernisation process could be mastered by means of design'. Gropius realised machines offered a great opportunity to mass-produce appealing and practical products. The Bauhaus vision was to embrace the new technological developments unifying art, craft, and technology. It was primarily focused on clean geometric forms and balanced visual compositions. The results were both beautiful and simplistic, from the modern 'Barcelona Chair' designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich to abstracted line-form paintings by Wassily Kandinsky. Each practice was examined, explored and experimented further by both the students and encouraging tutors. ( the chair pic) Futuristic designs for the real world were being considered with various mediums including wood, metal and glass. Graphic designers such as MoholyNagy, avid user of red and experimental layouts, set strong design trends. He was not shy to augment the typography by standing it vertically or diagonally on the page - as designers, we know this is a difficult technique to implement. ( typo) Closure Political pressure and constant scrutiny by the Nazi movement (which strongly opposed modernism in favour of classicism) continued to cast a shadow over the school. In 1928 Gropius resigned and was then succeeded by Hannes Meyer. The school carried on with practice as usual. In the 1930s the Bauhaus received criticism from the Nazi writers Wilhelm Frick and Alfred Rosenberg, labeling the Bauhaus 'un-German' - not agreeing with the modernistic styles the school was predominately based on. The writers characterised the Bauhaus as a front for Communists, Russians, and social liberals. Further pressure from the Nazi régime forced the Bauhaus to close on April 11, 1933. With many design movements, the outcomes look out-dated over the years. In contrast, the Bauhaus philosophy has had a constant influence on all forms of design. Most major cities incorporate design elements from this 94-year-old theory 'form follows function' - such as white walls, clean lines and glass - which came from a school that only existed for fourteen years. http://www.creativebloq.com/design/easy-guide-design-movements-bauhaus8134146 THE BAUHAUS MOVEMENT, GERMANY: 1919 to 1933 Written by Brian Kievning INTRODUCTION The German word Bauhaus essentially means “House of Building or Building School”. This simple name historically has come to mean much more than that. For some, the Bauhaus is synonymous with the greater term modernism. For others, the Bauhaus is a type of font or an architectural design style. For the design student, the Bauhaus Movement is considered one of the most important design movements in the twentieth century. In light of all the different understandings of what the Bauhaus is, there is something more important, the ideologies and methods that were taught there. These methods are often overlooked and relegated only to what students and members of the Bauhaus created as a result of their teaching rather then how they were educated. Burton Wasserman stated in a paper about the Bauhaus that, “above all, the Bauhaus was a place where powerful ideas and creative action were vigorously generated by talented and lively people” (Wasserman, 1969, p. 19). Wasserman also wrote that, “Since the Bauhaus proved to be so remarkably relevant to the present, hardly any post high school art program is in existence today which does not reflect the influence of Bauhaus theory and practice” (Wasserman, 1969, p. 19). For many the Bauhaus is considered an art-related movement and school, however upon a closer inspection of the methods and the principles that the Bauhaus was founded on, one will find that the Bauhaus Movement relates not only to the historical roots of technology education and design education, but that these methods are increasingly more relevant today. In fact, they are relevant to the technology educator that exists within a modern world driven by machines that design the products we use. The technology educator will also find that the multidisciplinary education like that of the Bauhaus will provide their students with an invaluable educational experience needed to succeed in an ever-changing world. TWO GOALS The Bauhaus concentrated on two main goals above all others. The first goal was aesthetic synthesis. This means the integration of all branches of art and craft under the primacy of architecture. The second goal according to Wick, from Teaching at the Bauhaus, was a synthesis of aesthetic production around the needs of a broad segment of the population. The opposite would have been designing for a proletariat or socially privileged section of the population (Wick, 2000, p. 52). Under Gropius it was stated that every student must learn a craft with the goal of architecture as the vehicle to a unified school. This merger of technology was to create the University of Design. It is important to note that during this time the protagonists for this change were architects: Bartning, Behrens, Fischer, Gropius, Schumacher and Riemerschmid. It was felt that the separation of architecture from painting, sculpture, and arts and craft was a disadvantage for all disciplines including architecture and the artistic disciplines. Essentially architecture would unite all disciplines to educate students to serve the greater populations of society using industry and the tools of production. These same goals are found in technology education, and impact the roles of the architect, engineer and industrial designer. http://bckievning.iweb.bsu.edu/Site/Historical_Movement.html The greatest practical achievements at the Bauhaus were probably in interior, product, and graphic design. For example, Marcel Breuer created many furniture designs at the Bauhaus that have become classics, including the first tubular-steel chair. He said that, unlike heavily upholstered furniture, his simple, machine-made chairs were "airy, penetrable," and easy to move. Though initially women were to be given equal status at the Bauhaus, Gropius grew alarmed at the number of women applicants and restricted them primanly to weaving, a skill deemed suitable for female students. Gunta Stölz and Anni Albers were major innovators in the area of textile design at the school's weaving workshop. In ceramic and metal design, a new vocabulary of simple, functional shapes was established. The courses in display and typographic design under Bayer, Moholy-Nagy, Tschichold, and others revolutionized the field of type. Bauhaus designs have passed so completely into the visual language of the twentieth century that it is now difficult to appreciate how revolutionary they were on first appearance. Certain designs, such as Breuer's tubular chair and his basic table and cabinet designs, Gropius's designs for standard unit furniture, and designs by other faculty members and students for stools, stacking chairs, dinnerware, lighting fixtures, textiles, and typography so appealed to popular tastes that they are still manufactured today. Gropius resigned his position in 1928 and named as his successor Hannes Meyer, a Marxist who placed less emphasis on aesthetics and creativity than on rational, functional, and socially responsible design. Meyer was forced to leave the Bauhaus in 1930, and Mies van der Rohe (Gropius's first choice in 1928) assumed the directorship. Mies's work as an architect is discussed below. Inevitably, activities at the Bauhaus aroused the suspicions of the reactionary political forces that finally brought about its closing in 1933. ( cabinet ) http://www.dieselpunks.org/profiles/blogs/art-history-practical