Response to Intervention Article Summary

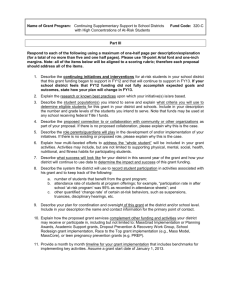

advertisement

Melissa Moxley (Yadkin Cohort) Vellutino, F., Scanlon, D., Small, S., & Fanuele, D. (2006). Response to Intervention as a Vehicle for Distinguishing Between Children With and Without Reading Disabilities: Evidence for the role of kindergarten and first-grade interventions. Journal of Learning Disabilities. Vol. 39, No.2, 157-169. Over many years, the means of identifying disabled readers have been through psychometric/exclusionary approaches. Researchers have become seriously disturbed with these approaches and they criticize them on many levels. These approaches do not account for a child’s prior educational background history nor do they distinguish between cognitive and experiential/instructional deficits, children are classified as reading disabled based on assessment instruments that have slim to non-existent diagnostic validity in relationship to reading, there is an inflation among the number of children that are classified as disabled readers, low expectations are created for the classified students and no direction for remedial or classroom instruction is provided by them (Vellutino, Scanlon, Small & Fanuele, 2006). The heavily weighed concerns motivated Vellutino, Scanlon, Small and Fanuele to embark on research that would provide a response to intervention to aid in distinguishing between cognitive and experiential/instructional deficits as primary causes of early and protracted reading difficulties as well as identifying at-risk children for reading difficulties before exposure to formal reading instruction (Vellution, Scanlon, Small & Fanuele, 2006). These researchers pursued their objectives by implementing an intervention study into a first grade population. The results in the study concluded that most at-risk readers’ difficulties could be remediated successfully and that instructional and experienced based knowledge were more than likely the key factors that cause the difficulties verses biological cognitive deficits. Intrigued with the results, Vellutino and colleagues contemplated a logical extension of the first grade study with trying to identify students entering kindergarten that might be at-risk and implementing intervention during the kindergarten year to prevent long-term reading difficulties. The extension study was a 5-year longitudinal study done with lower-middle to upper-middle-class background children in upstate New York schools. The study began in the children’s kindergarten year where the schools were split into project treatment and comparison groups for the study. The comparison groups received no intervention at all while the project treatment groups were broken into small (2 to 3 children) groups and received intervention in emergent literacy skills twice a week for 30 minutes each with a certified teacher (trained by project staff) outside the children’s regular classrooms. Short term effects were evaluated during December, March and June with a screening battery consisting of letter identification and phonological awareness assessments. June’s assessment data indicated that the project treatment groups performed considerably better than the comparison groups on the majority of the administered assessments. The researchers thought it was rational to imply that intervention implemented in kindergarten to at-risk readers could significantly improve their foundational literacy skills and aid in their preparation for reading instruction in first grade (Vellutino et al., 2006). The study continued onward into first grade and the children who had already been identified as at-risk readers in kindergarten continued with intervention. However, Vellutino and colleagues wanted to distinguish between the severe at-risk children that still needed intense intervention in first grade and those students that were less at-risk whom only needed minimal intervention. At the beginning of first grade, they administered subtests from the WRMT-R (Woodcock Reading Tests-Revised) and separated the children into five groups (DR- Difficult to Remediate, LDR-Less Difficult to Remediate, NLAR-No Longer At Risk, AvIQNorm-Average IQ & AbIQNorm-Above Average IQ). The results from the assessments indicated that implementing early intervention for at-risk kindergarteners is a resourceful first step in preventing reading failures as well distinguishing between slightly behind readers (ones that need only a little “boost” in order to be on grade-level) and the severely at-risk readers that will need continuous intense intervention not only in first grade but perhaps beyond in future grade levels. To provide additional reinforcement for these suggestions, they administered the Word Identification and Word Attack subtests from the WRMT-R and the Reading Comprehension subtest on the WIAT (Wechsler Individual Achievement Test) at not only the end of the children’s first grade year, but their second and third grade years as well (Vellutino, Scanlon, Small & Fanuele, 2006). The results of the 5 year study revealed students in all groups except the DR group were able to perform at solidly average levels on all of the reading achievement measures at the end of first, second and third grade. This indicated the proof that most children identified as at-risk readers in kindergarten could prevail over long-term reading difficulties if identified early and provided intervention in kindergarten. The DR (difficult to remediate) group’s scores were within the average range on all the literacy measures of the tests at the end of first grade, but the group’s scores dropped well below average on the word-level measures at the end of their second and third grade years (Vellutino, Scanlon, Small & Fanuele, 2006). In other words, the difficult to remediate (DR) group did show growth and gains in reading achievement from the extra intervention they received in first grade. However, in order to strengthen and preserve their gains towards becoming independent readers beyond first grade, they would have needed additional intervention to have continued through second and possibly third grade. Based on the results of the study, Vellutino, Scanlon, Small and Fanuele were able to conclude that starting in kindergarten to identify children that are at-risk in reading difficulties and providing them with early intervention is an efficient strategy for making a distinction between experientially and cognitively based causes of reading difficulties. They also revealed students that continued to be at-risk beyond first grade needed additional intervention as well in order for them to continue to make gains in functional literacy skills. Another insight into their findings aimed directly at classroom instruction. If classroom educators are not providing children with sufficient, adequate, direct and remedial instruction then how can the children grow and maintain functional literacy skills needed to become independent learners and readers?