Sinclair Thomson, New York University, “Times of Insurgency

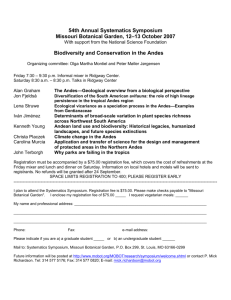

advertisement

Sinclair Thomson (NYU) Yale Conference, “Reframing Latin America’s Nineteenth Century” 27-28 February 2015 The Beginning of the End: Debating Colonial Crisis and the Origins of Independence in the Southern Andes According to the currently dominant historiographic narrative about Latin American independence, “Everything begins, as is well known, with the abdications of Bayonne” (F.X. Guerra). The prevailing notion among scholars is that the Napoleonic invasion of 1807, which provoked a peninsular crisis of sovereignty for the Spanish monarchy, triggered a chain reaction that would lead to the eventual separation of Latin American territories from the Iberian metropole. In epochal terms, this sharp and sudden rupture amounted to a mutation from Ancien Régime to Modern politics. From the perspective of the southern Andes, this narrative seems forced and awkward since a wealth of evidence new and old suggests that the colonial order in the region underwent profound turmoil in the late eighteenth century and that it never fully recovered in the aftermath of the powerful indigenous insurgencies of the early 1780s. The narrative of rupture in 1808 relies on artificial notions that the turbulence of the 1780s was of a pre-modern or pre-political nature – by this account, the Andean movements were tax revolts which hinged on a conception of a 1 legitimate Hapsburg colonial pact, backwards-looking attempts to restore a preconquest political order, or typical and transparent old-regime jacqueries with limited political horizons. Drawing on my own work and that of colleagues working on the southern Andes, I wish to question the idea of an epochal and epistemic rupture initiated in France and Spain in 1808 (“everything begins with Bayonne”) and to rethink the relationship between the Andean insurrection of the 1780s and the political culture and mobilizations in the same region in the independence era. This approach need not resuscitate a historia patria about precursors and immanent teleologies that would lead to the modern nation-states. Nor would the point be to ascribe an alternative indigenous modernity to Tomás Katari, Tupac Amaru, and Tupaj Katari and the movements they led. By questioning the contending nationalist and Hispanist narratives, and stripping away the teleological assumptions about the advent of modernity built into both, I believe we can recover a more politically complex and compelling history for the period. We can see, for example, the ways in which political discourse, strategy, and practice in the independence moment derived from earlier references, patterns, and outcomes from the revolutionary moment of the 1780s. At the same time, we can see the ways in which local political cultures and subaltern actors contributed to the independence dynamics. This is not to deny the importance of contingency, short-term conjunctural dynamics, and political innovation in the new revolutionary moment after 1808. But this approach can allow us to restore a deeper sense of the political temporalities and causal dimensions underlying the crisis of the colonial regime in Andes. 2