Words Their Way-Ch7

advertisement

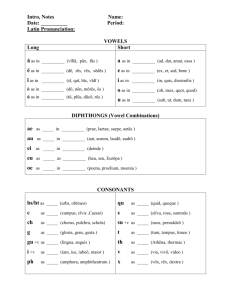

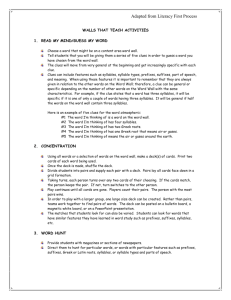

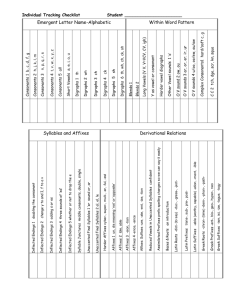

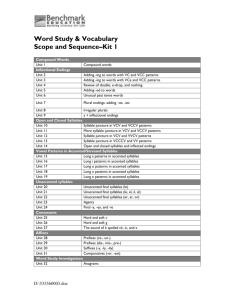

Words Their Way Chapter 7: Word Study for Intermediate Readers and Writers: The Syllables and Affixes Stage Beginning in second and third grade for some students, and fourth grade for most, cognitive and language growth supports movement into the syllables and affixes stage of word knowledge. Although students have been reading, and even writing, words of more than one syllable for some time, it is during this stage that they systematically study the generalizations that govern how syllables are joined and how affixes (prefixes and suffixes) affect spelling, meaning, and use of base words. Two key ideas of this stage: It demonstrates to students how much they already know about spelling a particular word—spelling is not an all-or-nothing affair. It demonstrates to students what they need to focus on when they look at a word. Students in the syllables and affixes stage are called intermediate readers— students who are not yet mature or advanced readers. During the syllables and affixes stage, students will learn to look at words in a new way—as two or more syllabic or morphemic units. During this stage, students are in the consolidated alphabetic phase in which they use larger chunks to decode, spell, and store words in memory as sight words. Intermediate writers become increasingly confident in their writing and are able to work on longer pieces over several days. In this stage, students’ own reading becomes the primary source of new vocabulary as they encounter within texts more and more words whose meanings they do not know. Remember that your own enthusiasm and curiosity about words is likely to enhance students’ word consciousness. One of your most important responsibilities for word study instruction at this stage is to engage students in examining how important word elements— prefixes, suffixes, and base words—combine; this morphemic analysis is a powerful tool for vocabulary development and figuring out unfamiliar words during reading. You can show students directly how to apply this knowledge by modeling the following strategy for analyzing unfamiliar words that they cannot identify in their reading: Examine the word for meaningful parts—base word, prefixes, or suffixes Try out the meaning in the sentence; check if it makes sense in the context of the sentence and the larger context of the text that is being read. If the word still does not make sense and it is critical to the meaning of the overall passage, look it up in the dictionary. Record the new word on a chart or in a word study notebook to be reviewed over time. **Part of your introductory routine might be for a student to look up a word and be ready to report to the group its meaning or multiple meanings. This is a good way to encourage regular dictionary use for an authentic reason. Once words have been selected, the following steps should be followed in the context of engaging activities: Activate background knowledge. Find out what students already know about the concept, and remind them of related concepts they have already learned. Explain the concept and its relationship to other concepts. Use graphic organizers, charts, or diagrams as needed to portray relationships among concepts. Discuss examples and non-examples. One category of suffixes, know as inflectional endings, includes –s, -ed, and – ing. One of the major challenges students face when adding –ed or –ing is whether to double the final letter of the base word. **The basic doubling rule is that when a suffix beginning with a vowel is added to a base word containing a single vowel followed by a single consonant, double the final consonant. This can be simplified as the one-one-one rule: one syllable, one vowel, one consonant—double. Rather than teaching rules, we suggest a series of word sorts that will allow children to discover the many principles at work. When students explore compound words, they can develop several types of understandings: First, they learn how words can combine in different ways to form new words. Second, the study of compound words lays the foundation for explicit attention to syllables. Third, students reinforce their knowledge of the spellings of many highfrequency, high-utility words in English that are compound words. Open and closed syllables dictate pronunciation: Open syllables (CV) end with a long vowel sound (tiger, reason) Closed syllables (CVC) contain a short vowel sound that is usually “closed” by two consonants (Tigger, racket). Syllable juncture patterns are another way of describing what happens when syllables meet. This is described on page 252. Identifying the vowel in unaccented syllables is one of the biggest challenges we all face as spellers. We prefer to use “base word” when referring to words that stand on their own after all prefixes and suffixes have been removed. Based words such as these are known as free morphemes. We use the term “word root” to refer to a word part that remains after all prefixes and suffixes are removed but is not itself a word that can stand alone. These roots are called bound morphemes. Many students will probably sort by the prefix, but don’t begin by discussing what the words and prefixes mean. Students should be encouraged to first develop their own hypotheses about the meanings of the prefixes as they consider the list of words. At the intermediate and middle grades, the following principles should guide instruction: Students should be actively involved in the exploration of words. Students’ prior knowledge should be engaged. Students should have many exposures to words in meaningful contexts, both in and out of connected text. Students need systematic instruction of structural elements and how these elements combine. Sequence and Pacing of Word Study in the Syllable and Affixes Stage: Early: Students will know how to spell the vowel patterns in most single syllable words but will make errors when adding inflectional endings. Middle: Students will usually add inflectional endings correctly but will make mistakes with syllable junctures within words and with unaccented final syllables. Late: Students who can spell most words correctly in the syllables and affixes categories on the inventory are transitioning into the derivational relations stage. Word study notebooks can be reviewed once a week and graded. In addition, the student contract (p. 77) and grading form (p.82) are helpful to monitor progress. Use the following basic routines for sorts: Model or have students sort under your direction and lead them in a discussion of the generalizations revealed by the sort. Students sort their own set of words and check their sorts. Oral and written reflections encourage students to clarify and summarize their understandings. Extension activities across the week reinforce and broaden students’ understandings. Organizing instructional-level groups for word study is a challenge but will best serve the needs of students, especially those who might be below grade level. The key to finding time for meeting with small groups is establishing routines, they become responsible for completing much of their work independently (both in class and at home) or with partners, and this leaves teachers free to work with other small groups.