REAA Continuing Education 2013 TOPIC 2

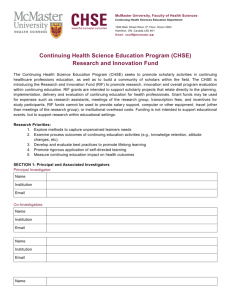

advertisement