“Bird of Passage”: Retrospective insights into the

advertisement

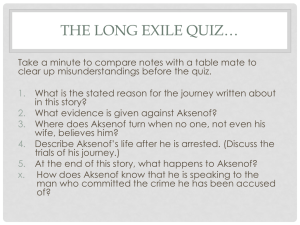

“Bird of Passage”: Retrospective insights into the affordances of artmaking as an adaptive method through a post-doctoral lens. “Bird of Passage”: Retrospective insights into the affordances of artmaking as an adaptive method through a post-doctoral lens. Abstract This paper explores the affordances of artmaking, within a higher education context, as an adaptive method, located at the commencement the doctoral journey for an artist/academic. Insights into knowledge production as a process of folding and becoming are viewed from a retrospective narrative using an auto-ethnographic perspective that unpacks the images and metaphors of the etching series “Birds of Passage”. Personal theories, about the role of creative practice in supporting learning and knowing, emerge through the deconstruction of the artist’s re-representational acts. The creative process is presented as a state of openness where adaptive knowledge struggles are hinged around knowledge disruption and where the creative arts provide an environment for the nurturing of uncertainty and change toward new knowledge. 1 Introduction The Bird of Passage etching series, are qualitative artifacts that imagine and attempt to predict the complexities of the learning journey of a doctoral traveler. The journeyer is an artist/academic and educator who used her imagined encounters on the pending epistemic shifts of the doctoral journey to focus awareness toward the unknown. Selecting to commence the journey thus was grounded in her understanding of learning as a somatic or embodied learning experience (O’Loughlin, 2006). The affordances of somatic or embodied learning draw on the senses and perceptions within a mind/body relationship (Kerka, 2002) and are present in the creative arts. Visual Art, through material representations draws on the affective self; the intellectual self and the imaginal dimensions of the learner. As such artmaking can be described as a technology of self that draws on the self-reflexive and attends to change phenomenon through creative activity towards transformation. On reflection artmaking, as an adaptive method, had become the enabler for new learning. Through imagining and representing the stress of the epistemic shifts within a doctoral journey that were already bearing down at the commencement of an academic learning journey, the etchings could be viewed as an attempt to re-member herself to her somatic ways of knowing. The etchings are a narrative of adaption, a real lived journey, they are deeply felt and they bridge her to the ways of knowing that had sustained her for many years as an artist and helped her reconcile the stress of disruption and opened her to the possibilities of new understandings. The Self Portrait and the Bird of Passage This paper takes an auto-ethnographic position (Holman Jones, 2005) and a narrative line, through the analysis of my etching series. Such a starting point acknowledges that retrospective and critical insights that draw on memory are selective, shaped and continually being folded, unfolded or refolded (Deleuze, 2006). More significantly it acknowledges that the production of this series of etchings, Bird of Passage, at the commencement of the doctoral journey, is located in-between the folding of being an artist and art educator and becoming an academic. 2 Figure 1, (1993) ‘the dance’, etching Figure 1 ‘the dance’, above was the final etching in the series. In this work I am the bird on the left. I dance with the cassowary, the symbol of academia. This native Australian bird is strong. His claws powerful, he forages in leaf litter and often leaves a destructive path behind him. I must embrace the cassowary. I must dance in the circle to have any hope of obtaining the ultimate prize of academia, the doctorate symbolized by the golden egg seen in the lower foreground. I dance with the cassowary alone in the circle. I use my artmaking and its adaptive powers to support both my doctoral research about identity, image and meaning and the performative, communicative practices of visual art students and as a tool of personal insight. Orientating this paper thus, allows for the recognition of “artifacts in the material world to be anchored in contexts and in subjectivities” (Roswell, 2011, pp. 332) and also recognizes that images hold traces of our deeply aesthetic and sensory world. Images as artifacts are as legitimate as other sources of information, such as observations, document analysis or interviews (Rowsell, 2011). The etching series Bird of Passage illustrated within the body of the paper, in retrospect, provided a means or the tools to break down past subjectivities, to scratch at past inscriptions of self in an attempt to make visible new actualities and new knowledge. It can also be described as arts-based research (Sullivan, 2005) that uses arts inquiry methods to communicate phenomena. The Bird of Passage etching series can be described as a self-performance and as a technology of embodiment (Jones, 2002) where the artist uses artmaking and its performative powers, as a means to fold the past and will oneself into the future. Somatic or embodied learning experiences attend 3 to ones senses and perceptions in a mind/body action and reaction (Kerka, 2002). In this series the images can be viewed as representations of the performing subject and as the narrative of the imagined becoming academic. Revisiting the etching series from an auto-ethnographic, analytical perspective may have the potential to contribute to a broader understanding-of the complexities of epistemological shifts for the artist/ academic. It may also provide an example of the the role of the visual arts beyond studying visual arts at tertiary level to work within the creative arts industries to its potential role in supporting the wider researcher disposition towards adaption and innovation. The etchings are therefore data that maps imaginal learning spaces or moments that are able to communicate critical intersects or disruptive junctures, between personal learning, academia and life. As such they offer evidence of an artist using her arts-based inquiry methods (Sullivan, 2005) as autoethnographic work that uses self-reflection and encourages a dialogue between self and the learning encounters. The etchings depict the critical relationship between the social and cultural dimensions of personal experience (Samaras, 2009) and mirror how all learning is grounded in the particular, while simultaneously acknowledging that this journey to academia is messy (Jones, 2011). Autoethnography is a form of critique and resistance that can be found in diverse literatures such as ethnic autobiography, fiction, memoir, and texts that identify zones of contact, conquest, and the contested meanings of self and culture that accompanies the exercise of representational authority. Mark Neuman (1996, p. 191) Such an approach will find the researcher analyzing and decoding her own images from philosophical and critical hermeneutic positions to seek out the emergent insights, about self as learner and other discourses that lurked as undercurrents during the doctoral journey and eventually surfaced as many deeply felt emotional responses. The period surrounding the generation and the production of the series of images was a period of knowledge disruption where academia and artistic insights were juxtaposed. Revisiting this time of struggle aims to shed light on the affordances of image generation as an autobiographical performance (Holman Jones, 2005; Spry, 2001) and its potential benefits to other learner travelers. It also aims to tease out how 4 the creation of images, as a performative act (Bolt, 2004), in this instance, as the performance narrative (Denzin, 2003) is able to situate the narrative within the forces of the surrounding discourses and provide a contested terrain. In so doing the performance narrative through visual representations, is able to support the adaptive processes of new knowledge production. Situating the Auto-biographical Performance: The Performativity, Symbolic and Material Pedagogies of the Visual Arts The ‘Bird of Passage’ series of etchings represented a visual narrative that initially attempted to translate the past and envisage the future. They provided a space for dialogue as debate and negotiation (Holman Jones, 2005) and are presented in this paper as the first auto-ethnographic iteration, conation or semiotic materialized performance of the self. In the second iteration they are the artifacts, the past stories told. They are echo objects (Stafford, 2007), they can be interrogated and interpreted to unearth those past experiences and the envisioned potential encounters from a new lens. The combination of analyzing both the performing self as artist and auto ethnographer in qualitative inquiry method presents both forms of narrative as sites of critical intervention into the social, political and cultural life (Holman Jones, 2005) of an individual. It draws on snapshots, artworks, metaphor and remembered moments in the narrative journey (Muncey, 2005). While it is a limited vantage point, it provides an opportunity to hold a mirror to oneself and find a unique space of inquiry, a space that can then be shared through autoethnographic narrative. On returning to university as a part-time lecturer in visual art education, I was working between the worlds of professional artist/designer and art educator. The reality of a steady income, to support the education of my family saw me shift slowly towards the world of a casual academic and the commencement of a doctoral learning journey. During this period of shifting identities, I sought to find a way to represent what lay ahead of me, and find clarity and relevance in the past experiences and knowledge I knew so well. Through the production of the etching series, ‘Bird of 5 Passage’, as a performance of self, I imagined my doctoral journey over the early stages of my doctoral study. It was a time of resistance, anticipation and adaption. I needed to shift my knowledge boundaries if I was to grasp new epistemological worlds. I needed to find ways to reconcile study and family. I hypothesized about the changing me. Using symbols and metaphor I found myself confronting and representing many of my fears and retelling existing narratives about myself as a learner. Most significantly, on reflection, it was an attempt to articulate exactly what this new learning journey would require of me. Amelia Jones refers to the self-portrait, as the eternal return a ‘technology of embodiment’ (Jones, 2002), where the artist presents themselves in a manner that transforms the notion of the subject. The affordances of the production of visual art works, as re-representational acts (Bolt, 2004) and deeply felt or embodied material practices provide multiple entry points into the pedagogies of the performance of self. The use of the figurative and new symbolic relationships, stood in place of the absent me and illustrated the learning journey, from artist and mother to academic researcher, as a body in process. Figure 2. ‘ and the story is told of the traveler’ The etching “and the story is told of the traveler’ (Figure 2, above) sees me positioned outside of self (yet I am the figure depicted, the traveler), in effect as the observer, narrator, but also the creator, both subject and object. I position myself within the discursive field of politico-socio-cultural understandings of academia and life events, all historically and socio-culturally located (Heidegger, 1962). I use my artmaking to enact re-iterations of imagined journeys. I allow my art, as a series, to 6 represent ontological change and the illustration of the learning as metaphoric meanings, embraces a refined representation of possibilities about the learning journey that lies ahead. Denzin (2003) in his article ‘The Call to Performance’ provides a manifesto into the role of performance-based disciplines in the generation of emancipatory knowledge. While his arguments are centered in the dramatic arts, the role of language and its reiterative powers to shape the self within the discourses of cultures and their accompanying texts it is also relevant to my journey, if one considers that artmaking is also a reflective, intellectual and embodied learning experience. This paper argues that visual texts permeate the post-literate age and equally carry the potential for symbolic inquiry, whether through the mimesis, or imitation of contemporary visual fields and discourses, or through poiesis, the construction of new re-representational imaging acts that generate new meanings with interpretive potential. My artmaking was thus a performance of self, a “struggle and intervention” (Denzin, 2003, pp. 188), where I challenged and resisted many of normative discourses and experiences surrounding the doctoral journey in education. I was making sense of the world through creative acts that involve “material thinking” (Bolt, 2006) and it was both a critical and experiential event. Material thinking, combined with symbolic and representational explorations opens up many possibilities for variability, sensitivity and new subjective experiences to emerge primarily through the materiality of creating or making images. Personal meaning is ascribed through the constant experimentation of re-representing within the processes of making, a process that acknowledges the contextual and conceptual understandings that surround ones world. More significantly, as described by Gilles Deleuze, artmaking is a plane of composition, in that it contains all past transformations of art, in a spatio-temporal framing (Grosz, 2009) which can be carried unconsciously by a culture or society. More significantly the forces within the production of the artwork or materialized event carry the becoming-sensation. Sensation for Deleuze, is ‘the zone of indeterminacy between subject and object’ (Grosz, 2009, pp. 84) and a space or territory that allows for the regrouping of forces (Deleuze & Guattari, 2002). It is 7 within the folds, and the folding that forces, as sensations, unfold and acquire new meanings. In ‘the story is told by the traveler’, I climb towards the inevitable mountain of the doctoral experience. The image holds clues about my expectations as I reach for the tree holding the fruit. Like others who have travelled this road, there is anticipation, knowing that nothing is certain or clear, and there is uncertainty, as many do not complete this journey. It is also an acknowledgement of excitement and effort. There is even menace for some doctoral travelers (Styles, February, 2000). The mountain carries a symbol of energy, round with radiating warmth. Lying beneath the ground is another figure, its position awkward, and the bird unsettling. Birds carry many cultural interpretations, they carry bad omens, they can be symbols of lightness, of flight, of travel and they may signify the gift of prophecy. ‘ Find your black holes and white walls, know them, know your faces, it is the only way you will be able to dismantle them and draw your lines of flight’ (Deleuze & Guattari 2002, p. 188) Artistic acts carry the capacity to expose the cultural and social forces that organize the spaces that surround us, and allow the forces to be realigned within the construct of creating identities or subjectivities. Thus the etchings in the Bird of Passage series are sites of meaning (Mansfeild, 2000). By using my symbolic and illustrative repertoire from my artistic world, I had in fact prepared myself well with the tools, or technologies of subjectivity to make the ‘coherency and rigidity of the social space leak”’(Parr, 2005, pp.147). I had provided myself with the aesthetic tools to examine my interiority and realize the infinite possibilities for my understanding of self as teacher, artist and academic. However, at the time I had no confidence, that creative arts methods that supported resilience, aesthetic insight and creativity developed in the studio learning environment (Hetland, 2007) could be useful. Nor that a periodic return to these practices, and creating my artworks in the context of studying for a doctorate would nurture a capacity to adapt and provide the skills needed to redefine myself along with unfolding new understandings surrounding knowledge production. (Baugh, 2005) Art and aesthetic experience through evolution Dissanayake (2008) claims has been essential in an individuals’ managing of their change environment. Managing change 8 requires understandings of one’s emotions, social interactions and conflicting viewpoints, anchoring one’s artmaking in the doctoral journey informs subjectivity. My artmaking actively supports in the deepest sense an understanding of the journeying self and ‘what comes to the point of view, or rather what remains in the point of view’ (Deleuze, 2006) becomes significant in the fluid shaping or folding of one’s story and is realized as a multiple productive self or body. Semiotics, the Image and Learning Recent research into neuroscience, art and learning provides yet another vantage point from which to examine how, as an artist, I used my semiotic insights about the work images do in creating knowledge and informing performative agency. Semiotics, as the image, is ‘a form of inquiry where humans shape raw sensory information into knowledge-based categories through sign-interpretation and sign creation’ (Danesi, 2010, p. ix). The images and their symbolic and metaphoric meanings connect my imagination and my life’s narratives. Huang (2009) commences his feature article about the neuroscience of art by establishing the traditional demarcations that have persisted in the separation between the arts and sciences. The arts are about imagination, subjectivity, narrative, and are often controversial in that they disrupt mainstream ideas, while the sciences are presented as logical, objective and factual. Huang presents the hypothesis that the arts and the sciences are co-investigators of reality. He substantiates his position through recent neuro-scientific research that has identified that when artists observe faces, they perceive and process information about this experience at a higher order of interpretation that an ordinary person. While artistic inquiry, as experimentation, cannot be verified through reproduction, over history they have ‘unlocked the secrets of the eye and the visual brain’ (Huang, 2009, p. 24). The neuroscientist, Zeki (2009) argues in this book ‘Splendours and Miseries of the Brain: love creativity and the quest for human happiness’, that evolutionary progress is not based on problem solving, but on concept formation as this is less risky for an individual whose synthetic brain is working to reconcile new knowledge, a process of learning that brings discontent for either a temporary or extended period of time. It is the imagination and creativity, as choice, intention or volition that may support learning. Creativity is a way of making up for the shortcoming of the working brain 9 (Zeki, 2009). Artists reconcile new knowledge, or the demands of others and society through the employment of intentional ambiguity and contradiction. Artists are often content with variation and paradox and these tools are effective in deepening interpretative possibilities of both artist and viewers. Volition and adaptivity The intentional acts of artists and their practices demonstrate that in learning the brain is continually making new connections and revising its neural patterns. This process involves change or adaption. Stables (2010), writing on semiotics and education, acknowledged that representations as communication are not distinct from thought and feelings and are not merely contextualized within socio-cultural communicative practices, but bound within the complexities of semiotic practices. Such an understanding acknowledges “human beings as learning ‘conatively’ rather than ‘cognitivel’ or ‘behaviourally’ (Stables, 2010, p. 22) and that learning is seen as selfinterpreting (Laverty, 2003). More significantly this way of knowing or being involves deeply felt acts (Finley, 2005), Grimshaw & Ravetz, 2005, O’Loughlin, 2006) that are generated and transformed by the volition of an individual. It may be that the intentional acts of the artist are all about using the power of perception and expression to produce representations, that can subsequently be objectified and then reflected upon, towards interpretation, and that these actions go part way in understanding the adaption capacities ascribed to artist, and referred to as creativity. (Hansen, 2000) describes learning as part of a complex, holistic and evolutionarybased system of intelligent adaptive behaviour. Current thought links the mind- bodyworld, emotions and learning (Immordino-Yang, 2007; Izard, 2009) and cognitive science and philosophy research (Varela & Shear, 1999; Weber & Varela, 2002) also centers the concept of creative adaptability as a key factor in self- sustainability or the ability to continually evolve ones identities in a changing society. Image as Object and Writing two Auto-ethnography iterations New struggles, such as a doctoral journey inevitably result in the rupture of current subjectivities and openness to the production of new subjectivities, and this new learning ‘might be understood as a topography of different kinds of folds’ (A. 10 O'Sullivan, 2005; M. O'Sullivan, 2007) when the effect of the self thus informs the self. It is this very territory that is unfolded in the autoethnographic journey of an artist’s doctoral learning, creative adaptive struggles and new knowledge production The generation of images provided a space for meaningful dialogue with the discourses surrounding me at the time: being an artist; mother; lecturer; and future researcher as subject positions as I sought to deal with the ambiguity and contradiction between the ways of knowing of the artist and those of academia. Writing from an autoethnographic perspective is the ‘other’ art. A storied narrative, able to take one deep inside oneself and weave the connections between the first iteration of the artist becoming academic with its second iteration, as the folding self, academic as artist. For Spry (2001) auto-ethnography is a performance, a creating of a self. This performative or auto-poietic (self-producing) attribute is deeply connected to creative acts. Making art, particularly art that represents personal experiences and the experimental investigation of self, can, therefore, be positioned as performing self or agency (Butler, 1990; Bolt, 2004; Holman Jones, 2005, 2007). For Spry, autoethnography is a form of critique and resistance symbolized as a ‘robust dance of agency’ (2001, p. 708). It locates auto-ethnography as a deeply embodied methodological praxis with transformative potential. The Spry quote carries the same metaphorical reference that I used in my Bird of Passage series. As the second iteration of the learning journey, the storied narrative from a postdoctoral orientation, I reflect on the first iteration of the becoming self, created in the context of beginning the doctoral journey. This second interaction is no less critical but is now informed by theory and an understanding that identities are fluid, deeply embodied and intellectually charged. This storied dance is between myself, and the spectator or audience (Figure 1). However, in this iteration I am stronger in my understanding that the semiotic, performative and material role of image construction is a significant adaptive affordance in my learning and possibly could be a tool for other adult learners as a arts-based self-study method (Samaras, 2011). 11 I work to critically deconstruct many of the feelings, symbols and metaphors that are present in my etchings and how, at the commencement of the journey I tried to visualize what I could expect to encounter. However, even with the capacities to envisage the future, I was not prepared. I was confronted by the knowledge demands placed on me as a doctoral student in education. I realized that I must completely rework myself, my beliefs and my knowledge base, move well outside my comfort zones and be prepared to defend my ideas, my methodologies and invent my own ways of representing my doctoral findings in the light of the learning journey. Folding, adaption and becoming through uncertainty The performance of self, as the creative act is integral to understanding adaptive knowledge, particularly when one acknowledges that identity is a liminal activity, where we are always positioned at the boundary between self, difference and becoming other. It is comfortable territory for the creative artist. New knowledge also lies in this terrain, between past understandings, the present context and future possibilities and disrupts. The individual is thus always in a process of being and becoming through uncertainty. Inquiry into the technologies of identities, as an aesthetics of existence or site of meaning, looks to transformative arts-inquiry practices where the creative and performative act produces self (Deleuze, 1990, Besley & Peters, 2007). Besley & Peters, in exploring Foucault’s ideas, presents the idea of the aesthetics of existence is an ethical self-constitution, where the choices and actions in these creative spaces shape our lives. Mel (2000) refers to the ritualized activities in creative acts as exploring the liminalities or the spaces ‘betwixt and between’ the act of becoming, the act of new knowledge generation. Being, as becoming, or subjectivity production is therefore presented as performative and iterative acts (Deleuze, 1990; Semetsky, 2003). The space of creative practice was to be revisited continually during the doctoral journey. Figure 3. (1993) ‘ pathways’, etching 12 The etching ‘Pathways’ ( Figure 3, above) followed on after ‘the story is told by the traveler’. In this work I have presented my imagined journey of possibilities, all be it somewhat naïve a representation on reflection, but one that embodied the concept of multiple alternate routes towards my goal. Significantly, the goal here is not the egg, the symbol of academic success but the image of energy that I had placed into the ground of my first image (Figure 2). As any commencing masters/doctoral student the particular pathway one will take often includes multiple forays along many differnce theoretical or philosophical paths, as well as the consideration of many inquiry questions. This representation clearly illustrates the consideration of such a journey, but I had already come to tentatively explore the idea that the main interest for me in life, and my work both as artist and researcher, was a fascination with identity, learning and the creative arts as an adaptive method. In retrospect I can say this was certainly the case and that the inclusion of the claws as a menacing and ambiguous symbol was part of an attempt to reconcile the demands of others, society and academia and possibly myself as equally an inhibitor to embracing change and uncertainty. Based strongly on life expereinces as sister, daughter, artist, teacher, wife and mother, I imagined this process as a balancing act. In Figure 4 (below) ‘balancing’ , I balance on top of a hill. Small birds peck at my head, they represent the demands of my students and my children. I am weighed down by the baggage of intellectual work and artistic life and I sit precariously on the very top of this mountain I must conquer. I can now see more than claws, it is a large bird and it has considerable force. 13 Figure 4, (1993) ‘balancing’, etching In analyzing this image from an autoethnographic lens, this image echoes not only the phenomenon of the lived experience as knowing (Husserl, 1969), but accommodates that this lived personal experience is firmly grounded in a hermeneutic phenomenological understanding (Laverty, 2003). Making your artwork the object of your self-reflection allows being and time to connect new imaginative and interpretive possibilities within the symbolic narratives of this image. Using my post-doctoral lens, this image now offers two meanings. At the time I felt trapped, wounded, burdened. I felt as if I was literally being pecked and violated and that I was balancing multiple roles in life. More importantly the bags I carried, or balanced were conflicting epistemological fields, that at the time appeared irreconcilable and my artwork illegitimate. A post-doctoral reading could be that it is not an image of domination, just invasion. Yes it is aggressive, the bird, academia is forceful and there are political and institutional constraints on me. But the bird is not on top of me I am on top of it. If what comes to the point of view and remains in view is an image of me ultimately ‘on top’, this representation as a conative act, is the will to adapt and survive. Thus the narrative of ‘on top of it’ becomes significant in the fluid shaping or folding of one’s story and in telling the story of one’s capacity to adapt. This is a far more positive reading than my original intent, I thought it would always be a balance, and I did not think academic knowledge could or would support my artmaking. Partaking of the Egg, the becoming narrative 14 In ‘partaking of the egg’ (Figure 5, below) I swallowed the egg and commenced the journey. In retelling this journey, an artist doing an educational doctorate, I acknowledge that “memories are fragmented, elusive and sometimes altered by experience” (Muncey, 2005, p. 1), none the less, this autoethnographic analysis has been the trigger for me to theorise around the role of artmaking and its affordances as a mechanism to support uncertainly and adaptive capacities. In The Fold (Deleuze, 2006) argues that the virtual and the possible inform both the actualization of ideas and the realization or the objectivity of the real world as material representations or bodies. Bodies ‘exist when, for whatever reason, a number of parts enter into the characteristic relation that defines it, which corresponds to its essence or power of existing’ (Baugh, 2005, p. 31). Bodies are thus defined by their constituting parts and are “forever realizing” (Deleuze, 2006, p. 137) towards something real or substantial. Deleuze (1990) challenges previous ideas about truth and positions it in terms of creativity and construction. Each individual creates their own truths through complex processes, made up of sensations and propositions. Williams (2005) talking of Deleuzian truth locates it in the complexity of art, literary works, or philosophy and the significance of their constituting components. Truth is constituted by both its destruction and by its transformative processes and truth, is more becoming over being, transformation and difference over sameness. Therefore each individual understanding of the world and knowledge is generated through a process of transformation “rather than projecting ourselves into an identifiable truthful future” (Williams, 2005). 15 Figure 5, (1993) ‘partaking of the egg’, etching Thus the coming to academia, study and visual art education after a significant period immersed in the world of art, both as artist and community artist was a daunting experience that could be told as a becoming narrative, the adaptive, the folding me. Immediately the journey saw me experience the dissonances between a visual semiotic world that had deep intrinsic and aesthetic value to me and the empirical, analytical, logical and written communicative practices of academia. The metaphor of folding (Deleuze, 2006) for the production of knowledge, provided a means of both practicing philosophy and art and a theoretical framework for reasoning learning. Folding is a process by which the inside of self is revealed from the outside and acts of folding allow the continuum of variations and traces of all understandings to re-emerge as new understandings. Folds overlay, they have orders, they have difference and they inform aesthetic insights. Artists are continuously folding, folding and unfolding in new ways, inventing folds on folds or folds within folds. When ones artwork becomes the object of inquiry, or an artist positions themselves as the viewer in an interpretive stance, one further unfolds. This unfolding may increase, refine or decrease possibilities. No fold is ever the same and folds always have difference. Yet academia appeared to be asking something else of me, I was challenged to seek empirical knowledge. The forces of the outside (or the cassowary) were folding the inside. Only when I took a retrospective post-doctoral analysis was I able to see that inside (me) had also become a fold of the outside and that uncertainty was a given, and necessary for learning. The folding metaphor (Deleuze, 2006) helped me reconcile and manage risk at my site of change and 16 understand the powerful way imaging acts work to generate possible new meanings. It also provided me with the philosophical reasoning that could help me both shape my own emergent academic identity with my doctoral inquiry into Identity, Image and Meaning: Beyond the Classroom . The narrative story about learning emergent from my retrospective examination of my artwork has helped me theorise about learning, change and the role of the creative arts. Learning, as folding, is an “an infinite work in process, it produces expression… the problem is not how to finish the fold but how to continue it’ (Deleuze, 2006, p.39). Learning is located in uncertainty, it is ‘free, moving and operative…[and makes one] …a living spirit’ (Dewey in Semetsky, 2003). Artmaking as learning is therefore an ontology of self, that grounds knowing the world through being and identity, between the world and self, between the inside and the outside. It folds time and memory and learning occurs at the points of dissonance and ambiguity it requires contestation, defense. Conclusion The paper hypothesizes that the role of artmaking as portraiture, in its affordances to sharpen imaginative processes toward becoming, is a significant adaptive method. More significantly, if the processes of artmaking are coupled with a critical analytical autoethnographic layering, the new territory unfolded in this space may provide a field where creative adaptive struggles and new knowledge production can be contested and explored. Such a critically reflective learning environment allows the inside to be folded and revealed on the outside as artworks, or being an object in the process of becoming (Deleuze, 2006). It also allows the material world to be anchored to a learning context and subjectivity. The subsequent reflexive capabilities afforded by the combination of artmaking and an autoethnographic narrative as interrogation provides another iteration of autopoiesis, another opportunity for self-experimentation or self-creation. A learning environment that develops reflexivity moves one towards epistemological awareness that considers the connections across and between theories. The following Spry’s (2001) quote from the words of Soyini Madison: 17 ‘Performance thrills me, theory does not, I would surely loose myself without performance, but I cannot live well without theory” (p. 706) Figure 6, (1993) ‘Bird of Passage, Arrival’, etching These words now aptly describe my current position in relation to the tensions that constitute my generation of new knowledge. I am the ‘Bird of Passage’ (Figure 6) above. I revisit the place where I began this autoethnographic journey, revisiting the place where I cultivate my creativity, a symbolic garden with regenerative energies, and others too, have travelled this journey (Zeki, 2009). I use my artmaking as an adaptive method. It serves as a metaphor for the duality of the artist/academic and illuminates the journey for myself and my audiences. References Baugh, B. (2005). Body. In A. Parr (Ed.), The Deleuze Dictionary (pp. 30-32). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Bolt, B. (2004). Art Beyond Representation, The Performative Power of the Image. London: I. B. Tauris. Deleuze, G. (2006). Deleuze, The Fold. London: Continuum. Denzin, N. K. (2003). The Call to Performance. Symbolic Interaction, 26(1), 187207. Finley, S. (2005). Arts-Based Inquiry. In N. K. L. Denzin, Y.S. (Ed.), The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research (3rd ed., pp. 681-693). London: Thousand Oaks, Sage. 18 Grushka, K. (2007). Identity, Image and Meaning Beyond the Classroom: Visual and Performative Communicative Practice in a Visual 21st Century., The University of Newcastle, Newcastle, Australia. Hansen, M. (2000). Becoming as Creative Involution?: Conceptualizing Deleuze and Guattari's Biophilosophy. Post Modern Culture, 11(1), 1-63. Hetland, L. W., E.; Veenema, S.; Sheridan, K. M. (2007). Studio Thinking, The Real Benefits of Arts Education. New York: Teachers College Press. Holman Jones, S. (2005). Autoethnography: Making the Personal Political. In N. K. L. Denzin, Y. S. (Ed.), The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research (3 ed.). London: Sage. Immordino-Yang, M. H. a. D., A. (2007). We Feel, Therefore We Learn: The Relevance of Affective and Social Neuroscience to Education. International Mind, Brain, and Education Society 1(1), 3-10. Izard, C. (2009). Emotion Theory and Research: Highlights, Unanswered Questions, and Emerging Issues. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 1-25. Jones, A. (2002). The "Eternal Return": Self-Portrait Photography as a Technology of Embodiement. Signs, 27(4), 947-978. Jones, A. (2011). Seeing the messiness of academic practice: exploring the work of academics through narrative. International Journal of Academic Development, 16(2), 109-118. Laverty, S. (2003). Hermeneutic Pehenomenology and Phenomenology: A Comparison of Historical and Methodological Considerations. International Journal of Qualtative Methods. Mansfeild, N. (2000). Subjectivity: Theories if self from Freud to Haraway. Sydney: Allen and Unwin. Muncey, T. (2005). Doing autoethnography. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 4(1), 1-12. O'Sullivan, A. (2005). Fold TheDeleuze Dictionary. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. O'Sullivan, M. (2007). 'Research quality in physical education and sport pedagogy' Sport, Education and Society, 12(3), 245-260. Rowsell, J. (2011). Carrying my family with me: artifacts as emic perspectives. Qualitative Research, 11, 331-346. Stafford, B. (2007). Echo Objects: The Cognitive Work of Images. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Styles, I. (February, 2000). Jabba the Hut: Research students' feelings about doing a thesis. Paper presented at the Flexible Futures in Tertiary Teaching, 9th Annual Teaching and Learning Forum Perth. Williams, J. (2005). Truth. In A. Parr (Ed.), The Deleuzian Dictionary (pp. 289291). Great Britain: Edinburgh University Press. 19