File - need help with revision notes?

advertisement

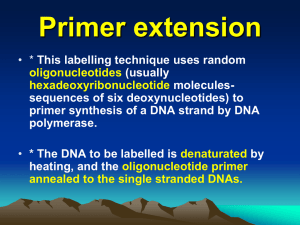

F215 Biology: Genomes and Genomics A genome is all of the genetic information within an organism. It is made of DNA divided into a definitive number of chromosomes. Genomics is the study of the whole set of genetic information in the form of the DNA base sequences that occur in the cells of a particular species. The human genome contains 3 billion bases. 22,000 genes are present; only 1.5% of bases are coding bases (that it, bases which code for a particular protein). The remaining DNA(often mistakenly referred to as ‘junk DNA’) is still important: control sequences, ‘fossil genes’ from our evolutionary past, parasitic DNA that can jump around the genome, inactive viral genomes and simple repetitive sequences (eg. TATATA) that are often found at the end of chromosomes (‘telomeres’). Exons are coding regions of chromosome; introns are non-coding regions. Comparative genomics: when we know the sequence of bases in a gene of one organism we can compare genes for the same proteins across a range of organisms. This comparative gene mapping has 5 main applications: o Identification of genes for proteins found in all or many living organisms gives clues to the relative importance of such genes to life. o Comparing genes of different species shows evolutionary relationships. The more DNA sequences the organisms share, the more closely related they are likely to be. When comparing closely related species, we need to look at fast evolving genes that are unique to the chosen species – like genes coding for their cells’ antigens. Species that are more distantly related must be compared by looking at genes that code for proteins fundamental to life processes that rarely change, that all organisms have in their genome, like genes for ribosomes and tRNA. o Comparing genomes can reveal the effects of mutations to DNA. Mutations in yeast cells have been found that cause unusually fast mitosis. The same gene has been found in humans, so experiments on yeast can be used to find drugs that could be useful to humans. o Comparing genomes of pathogenic and similar non-pathogenic organisms can be used to identify the base sequences that are most important in causing disease. This can lead to identifying targets for more effective drugs and vaccines. o Analysing DNA of individuals can reveal mutant alleles or the presence of allelesassociated with increased risk of particular diseases like heart disease or cancer. Genetic fingerprintingis a technique that can be used to identify individuals. It works because every individual has a unique sequence of nucleotide bases in their genomes. In order to carry out genetic fingerprinting, DNA samples are cut at specific sequences of nucleotides. DNA samples from different individuals will be cut into a different number and different size of ‘restriction fragments’, so when the DNA samples are separated according to size, a person can be identified from the unique fragment pattern. The three key ingredients for genetic fingerprinting are: restriction enzymes, gel electrophoresis and gene probes. Restriction enzymes (restriction endonuclease enzymes) cut DNA at a specific base sequence known as a restriction site. Restriction enzymes are produced naturally by prokaryotes where it evolved to provide a defence mechanism against invading DNA viruses called F215 Biology: Genomes and Genomics bacteriophages.The bacteria’s own DNA is methylated to protect it from the effects of the enzyme. Restriction enzymes recognise a specific sequence of nucleotides and produce a double stranded cut in the DNA. Two incisions are made, one through each sugar-phosphate backbone of the DNA double helix. Restriction enzymes usually make a staggered cut through the DNA, leaving sticky ends. Any two people will have small differences in their DNA. Each person’s DNA will be cut into a different number and size of fragments; these are ‘Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphisms’. The mix of fragments will be the person’s fingerprint. Gel electrophoresis separates DNA fragments based on their size. DNA fragments are pipetted into a well at one end of an agarose gel with a buffer solution to stabilise pH and ensure that DNA stays double stranded. A size standard is placed into the well at the end of the gel to allow for the quick estimation of the size of unknown fragments in other lanes. DNA fragments migrate to the positively charged anode (DNA is negatively charged due to the phosphate groups). Small fragments migrate quicker and further than larger fragments. The Southern Blot technique is used to create an exact but more durable copy of the gel. A nylon sheet is placed over the DNA fragments. Paper towels are placed over the top so DNA fragments are drawn out of the gel and onto the nylon sheet. DNA probes are a short single stranded piece of DNA (50-80 nucleotides) complementary to a piece of DNA being investigated. The probe is labelled in one of two ways: using a radioactive marker that can be revealed by exposure to photographic film or by using a fluorescent marker that emits a colour on exposure to UV light. DNA fragments are made single stranded by adding alkali. When added to DNA fragments, the probe will anneal (form hydrogen bonds) with complementary sequences and we are then able to identify the position of specific genes on the gel. Genetic fingerprinting is used in paternity testing to identify a child’s biological father and in crime scene investigations to find if a suspect was present at the scene of a crime. DNA Chips and Microarrays: this technology allows us to rapidly determine which genes are expressed by a cell or tissue. When a gene is expressed, it is transcribed into mRNA. mRNA from the tissues in question is isolated and then converted into complementary strands of DNA (cDNA) by the enzyme reverse transcriptase. To distinguish between the cDNA of the different cells, they are fluorescently labelled. A DNA chip contains 60,000 or more different DNA sequences called probes. The probes are single stranded represent a unique region of a gene in the genome. cDNA samples are mixed together and added to the chip. cDNAs that are complementary to probes on the chip will hybridise with DNA and stick to that location on the chip. Unbound cDNAs are washed away. A scanner detects patterns of hybridisation by sensing the fluorescent signals. Each area of the chip contains a known DNA sequence, so the identities of the hybridising cDNA can be determined. Using this, we can find which genes are expressed differently in cancerous or diseased tissue, so we may be able to design better treatment strategies. Polymerase chain reaction: this reaction is able to make thousands of copies of just one particular gene from small quantities of mixed DNA. If scientists have a limited amount of DNA to work with, they need to replicate it so they have 1000s of copies before the investigation begins. PCR is useful when we need to amplify DNA from a crime scene, or when we need to replicate DNA before genetic engineering or before gene therapy. PCR needs 3 key ingredients:free DNA nucleotides, primers and Taq polymerase enzyme. F215 Biology: Genomes and Genomics Free nucleotides must be activated with 3 phosphate groups. Taq polymerase is the DNA polymerase enzyme from the thermophillic bacteria Thermus Aquaticus. This bacterium can survive at temperatures of 50-80° degrees. It is thermostable – it allows DNA to be heated to melting point and the enzyme is not denatured. Primers are short artificial nucleotide sequences, 4-20 bases in length, which are complementary to the ends of the gene of interest. Primers identify the start point for DNA replication by Taq polymerase. Taq polymerase would be unable to bind directly to single stranded fragments. The procedure in Polymerase Chain Reaction: 1. Heat DNA to 95° to break the hydrogen bonds holding the DNA double helix together, so making the samples single stranded. 2. Add primers and reduce temperature to 55° allowing the primers to anneal to the ends of the gene of interest. 3. Heat to 72° to allow the Taq polymerase to bind. The DNA polymerase enzyme adds free nucleotides to the unwound DNA, extending the double stranded section. 4. Repeat the process; the amount of DNA increases exponentially. DNA sequencing – based upon interrupted Polymerase Chain Reaction and Electrophoresis DNA sequencing uses the principles of PCR and electrophoresis. The DNA strand to be sequenced is copied millions of times using Taq polymerase, primers and free nucleotides (just as in PCR). The DNA fragments produced are then sorted according to size by electrophoresis. Within the sequencing mixture, some of the nucleotides are fluorescent dideoxynucleotides. These nucleotides are modified and if they are added to the growing chain, the DNA polymerase stops the replication reaction and the DNA strand will end this fluorescently-marked dideoxynucleotide. The DNA strand is heated to 95° to denature the DNA making it single stranded. Mixture is cooled to 55° so that primers can anneal at the 3’ end of the template strand. Heat the mixture to 72° so that Taq polymerase will attach. The polymerase enzyme will add nucleotides according to complementary base pairing. If a fluorescent dideoxynucleotide is incorporated into the growing chain, the replication reaction will stop. The fragment will remain this length with the fluorescent dideoxynucleotide as the final base. As the reaction proceeds, many molecules of DNA are made. The fragments generated vary in size. In each case, the final added nucleotide is tagged with a specific colour. An automated DNA sequencer separates the fragments by size. This is like a vertical gel electrophoresis apparatus with a laser at one end. The laser will read the colour sequence of the dideoxynucleotides at the end of each fragment. We can now identify the base type at the end of each fragment and the base’s position along the DNA molecule. F215 Biology: Genomes and Genomics Sequencing a genome – BACs Genomes are first mapped to identify which chromosome or which section of the chromosome they have come from. The location of microsatellites are used – these are short runs of repetitive sequences of 3-4 base pairs found in several thousand locations in the genome. Samples of the genome are sheared (mechanically broken) into smaller section of around 10000 base pairs. These sections are placed into bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) and transferred into the cells of E.Coli bacteria. BACs are man-made pieces of DNA that can replicate inside a bacterial cell. As the bacterial cells grow in culture, many clones of the DNA sections are produced. These cells are referred to as clone libraries. In order to sequence a BAC section, cells containing specific BACs are taken and cultured. The DNA is extracted and restriction enzymes are used to cut it into a number of smaller fragments. Different restriction enzymes are used on a number of different samples to give different fragment types. The fragments are separated by electrophoresis. Each fragment is sequenced using an automated process. Computer programmes then compare overlapping regions from the cuts made by different restriction enzymes in order to reassemble the whole BAC segment sequence.