pre-operative assessment

advertisement

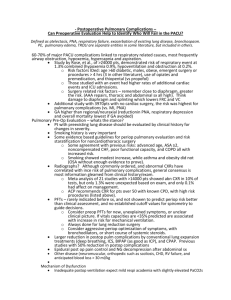

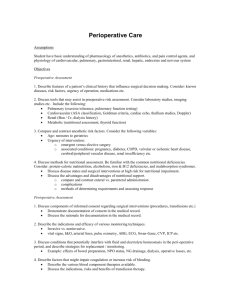

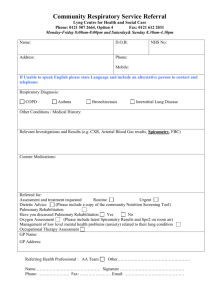

PRE-OPERATIVE ASSESSMENT OF THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM INTRODUCTION: Physicians are often asked to evaluate a patient prior to surgery. The medical consultant may be seeing the patient at the request of the surgeon, or may be the primary care physician assessing the patient prior to consideration of a surgical referral. The goal of this evaluation is to determine the risk to the patient of the proposed procedure and to minimize known risks. Postoperative pulmonary complications contribute significantly to overall perioperative morbidity and mortality. In a study of patients undergoing elective abdominal surgery, as an example, pulmonary complications occurred significantly more often than cardiac complications and were associated with significantly longer hospital stays1. The United States National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) also found that postoperative pulmonary complications were the most costly of major postoperative medical complications (including cardiac, thromboembolic, and infectious) and resulted in the longest length of stay2. As the impact of pulmonary complications following surgery has become increasingly apparent, estimation of their risk should be a standard element of all preoperative medical evaluations. DEFINITION OF POSTOPERATIVE PULMONARY COMPLICATIONS: The reported frequency of postoperative pulmonary complications in the literature varies from 2 to 70 percent. This wide range is due in part to patient selection and procedurerelated risk factors, although differing definitions for postoperative complications account for much of the variability and make comparison of reported incidences across different studies difficult. One proposed definition is a pulmonary abnormality that produces identifiable disease or dysfunction that is clinically significant and adversely affects the clinical course 3. This would include: Atelectasis Infection, including bronchitis and pneumonia Prolonged mechanical ventilation and respiratory failure Exacerbation of underlying chronic lung disease Bronchospasm4 EFFECT OF MEDICAL CONSULTATION ON SURGICAL OUTCOMES Several investigators have studied whether internist care of surgical patients is beneficial. These studies have shown that internists identify medical conditions that are related to surgical outcome and often recommend interventions for these conditions 5-7. In addition, physicians occasionally cancel or delay surgery so that medical conditions can be optimized. Studies report conflicting findings regarding the effect of medical consultation on length of stay. Two studies demonstrated a decrease in length of stay when an internist routinely cared for patients after thoracic surgery8 or hip fracture surgery9, while another showed similar or increased costs and length of stay for consulted patients, and no improvement in glucose control, use of perioperative beta blockers, or prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism10. No study has shown a decrease in perioperative morbidity associated with medical consultation, although there were fewer minor complications in the group of hip fracture patients who were cared for by hospitalists9. Nevertheless, the practice of medical consultation is widespread and, assuming consultants make evidence-based recommendations that improve surgical outcomes, it is reasonable to infer that consultation will improve the care of the surgical patient if consultative recommendations are implemented GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF CONSULTATION An effective and satisfactory medical consultation can be performed when some general principles are followed10 Determine the question and respond to it. Establish the urgency of the consultation and provide a timely response. “Look for yourself”; confirm the history and physical examination and check test results. Be as brief as appropriate; be definitive and limit the number of recommendations. Be specific, including medication details. Provide contingency plans; anticipate potential problems and questions. “Honour thy turf”; don't steal other physician's patients. Teach with tact; consult, don't insult. Talk is cheap and effective; direct verbal communication is crucial. Follow-up to ensure that recommendations are followed In doing a pre-operative assessment, one should seek factors that might put the patient at higher than average risk and propose plans to reduce this risk. Risks are specific to the individual patient, the type of procedure proposed, and the type of anesthesia selected. If no such risks are present, the final statement should be that the patient is at average risk for the proposed surgery. Studies that have examined the compliance of referring surgeons with the recommendations of physicians have found that compliance ranges from 54 to 95 percent depending upon the setting11. The following factors or advice have been shown to improve compliance with the physician's recommendations: As discussed previously, the central reason for the consultation request needs to be clearly stated, understood, and addressed The physician should respond in a timely fashion. Urgent consultations should be seen promptly, and elective consultations should be answered so as not to cause a delay in surgery. In general, all consultations should be done within 24 hours, and preferably the same day as requested. Any anticipated delays should be communicated immediately to the referring surgeon. The physician's recommendations should be definitive, prioritized, and precise. The number of recommendations should be limited when possible, preferably to five or fewer. Recommendations identified as "crucial" or "critical" are more likely to be followed. The physician should use definitive language and specify relevant recommendations. Recommendations for medications should specify the drug name, dose, frequency, route of administration, and duration of therapy. Alternatives to a recommended therapy should be mentioned if available. Therapeutic recommendations are more likely to be followed than diagnostic recommendations, but recommendations to start therapy may be less likely to be followed than those to continue or discontinue therapy. Direct verbal communication with the requesting surgeon is preferable to communicating via the chart. Frequent follow-up visits documented with progress notes are key in improving compliance with the physician’s recommendations. How often a physician needs to see a patient will depend upon the patient's medical problems and type of surgery. When the physician no longer needs to follow the patient, he should write a note indicating that he is signing off the case. He should also make arrangements to assure continuity of care for medical problems after the patient is discharged. PERIOPERATIVE PULMONARY PHYSIOLOGY Postoperative pulmonary complications follow logically as an extension of normal perioperative pulmonary physiology. Reduced lung volume after surgery is a major factor contributing to the development of postoperative pulmonary complications. Thoracic and upper abdominal surgery is associated with a reduction in lung volumes in a restrictive pattern as follows: Vital capacity (VC) is reduced by 50 to 60 percent and may remain decreased for up to one week. Functional residual capacity (FRC) is reduced by about 30 percent. Diaphragmatic dysfunction appears to play the most important role in these changes; postoperative pain and splinting are also factors. Reduction of the FRC below closing volumes contributes to the risk of atelectasis, pneumonia, and ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) mismatching. Microatelectasis results in areas of the lung that are perfused but not ventilated, leading to impaired gas exchange with consequent postoperative hypoxemia. A decrease in tidal volume, loss of sighing breaths, and increase in respiratory rate occur after abdominal and thoracic surgery and contribute to the risk of complications. In addition, residual effects of anesthesia itself and postoperative opioids both depress the respiratory drive. Inhibition of cough and impairment of mucociliary clearance of respiratory secretions are factors that contribute to the risk of postoperative infection. Lower abdominal surgery is associated with similar changes, but to a lesser degree. Reductions in lung volumes are not seen with surgery on the extremities 12. PATIENT RELATED RISK FACTORS Risk factors for pulmonary complications can be divided into patient related and procedure related risks. The potential patient related risk factors studied include the following: AGE The influence of age as an independent predictor of postoperative pulmonary complications has been questioned. Early studies suggested an increased risk of pulmonary complications with advanced age. These studies, however, were not adjusted for overall health status or the presence of known pulmonary disease and subsequent studies did not reliably demonstrate age as a predictor of postoperative complications. The risk of surgical mortality was similar across age groups when stratified by American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class13. A more recent systematic review prepared for the American College of Physicians estimated the impact of age on postoperative pulmonary complications among studies that used multivariable analysis to adjust for age-related comorbidities. This review made the novel observation that age >50 years was an important independent predictor of risk. When compared to patients <50 years old, patients aged 50 to 59 years, 60 to 69 years, 70 to 70 years, and ≥ 80 years had odds ratios (OR) of 1.50, 2.28, 3.90 and 5.63, respectively. Therefore, even healthy older patients carry a substantial risk of pulmonary complications after surgery.14 CHRONIC LUNG DISEASE Known chronic lung disease is an important patient-related risk factor for postoperative pulmonary complications. Unadjusted relative risks of postoperative pulmonary complications have ranged from 2.7 to 6.0. An early prospective study assessed pulmonary risk in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as established by clinical findings and chest radiographs. Complications occurred in 26 percent of patients compared with 8 percent of controls. In another report, patients with severe COPD were six times more likely to have a major postoperative pulmonary complication after abdominal or thoracic surgery than were those without COPD. Findings of decreased breath sounds, prolonged expiration, rales, wheezes, or rhonchi correlated with an increased risk for postoperative complications in one case control study. A more recent systematic review, however, found that impact of COPD on postoperative pulmonary complication rates was less than previously estimated. Among studies that used multivariable analysis to adjust for patient-related confounders, the odds ratio for postoperative pulmonary complications was 2.3614. Despite the increased risk of postoperative pulmonary complications in patients with obstructive lung disease, there appears to be no prohibitive level of pulmonary function below which surgery is absolutely contraindicated. This was illustrated in a study of 12 very high risk patients as defined by older criteria of inoperability (FEV1 <1 litre), only 3 of 15 surgeries were associated with postoperative complications and there were no deaths. In another report of surgery in patients with severe COPD (FEV1 <50 percent predicted), mortality was 5.6 percent (primarily related to a high mortality rate after cardiac surgery) and severe postoperative pulmonary complications occurred in 6.5 percent. The benefit of surgery must be weighed against the known risks; even very high risk patients may proceed to surgery if the indication is sufficiently compelling15 ASTHMA Despite early reports indicating that patients with asthma had higher than expected rates of postoperative pulmonary complications, more recent studies have found no link for patients with well controlled asthma. The largest such report studied 706 patients with asthma undergoing general surgery. There were no incidents of death, pneumothorax, or pneumonia in the entire sample. Fourteen minor complications occurred including bronchospasm (12) and laryngospasm (2). One patient developed postoperative respiratory failure without sequelae. Patients with asthma who are well controlled and who have a peak flow measurement of >80 percent of predicted or personal best can proceed to surgery at average risk.16 SMOKING Smoking is a risk factor for post operative pulmonary complications, as has been demonstrated since the first report in 1944. Smoking increase risk even among those without chronic lung disease. The relative risk of pulmonary complications among smokers as compared with non-smokers ranges from 1.4 to 4.3. Unfortunately the risk declines only after eight weeks of preoperative cessation. Warner et al prospectively studied 200 smokers preparing for coronary artery bypass surgery and found a lower risk of pulmonary complications among those who had stopped smoking at least eight weeks before surgery than among current smokers (14.5% vs. 33%). Paradoxically, those who had stopped smoking less than eight weeks earlier had a higher risk than current smokers17. OBESITY Physiologic changes that accompany morbid obesity include: Reduction in lung volume Ventilation/perfusion mismatch Relative hypoxemia These findings might be expected to accentuate similar changes seen with anaesthesia and increase the risk of postoperative pulmonary complications. However, obesity has not consistently been shown to be a risk factor for postoperative pulmonary complications. A systematic review found that, among eight studies using multivariate analysis, only one study identified obesity as an independent predictor14 and therefore obesity should not affect patient selection for otherwise high-risk procedures. OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNOEA Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is an emerging risk factor for postoperative pulmonary complications. It is well-appreciated in the anesthesia literature that OSA increases the risk of critical respiratory events immediately after surgery, including early hypoxemia and unplanned reintubation17. A subsequent study followed 172 elective surgical patients who had clinical features suggesting OSA (snoring, excessive daytime somnolence, witnessed apneas, or crowded oropharynx). Patients underwent home oximetry testing preoperatively, and were stratified on the basis of the number of oxygen desaturations per hour of at least 4 percent (ODI4%). Compared to patients with better indices, patients with an ODI4% of >5 were more likely to have postoperative respiratory (8 versus 1 percent) and cardiac (4 versus 1 percent) complications. Pulmonary complications included hypoxemia, atelectasis, and pneumonia 18. While the literature is still emerging, we should consider OSA to be a probable risk factor for pulmonary complications after surgery. Whether patients without known OSA should be screened for OSA prior to elective surgery, such as through use of a standardized questionnaire, are unknown and the subject of current study. PULMONARY HYPERTENSION Pulmonary hypertension increases pulmonary complication rates after surgery. This appears to be true regardless of the underlying etiology of the pulmonary hypertension. As an illustration, authors studied 145 surgical patients with pulmonary hypertension, excluding those where the condition was due to left heart disease 19. Complications included respiratory failure (41), cardiac dysrhythmia (17), congestive heart failure (16), renal insufficiency (10), and sepsis (10). Risk predictors included: History of pulmonary embolus NYHA functional class ≥ 2 Intermediate or high risk surgery Duration of anesthesia > 3 hours. A subsequent study compared 62 patients with pulmonary hypertension of any etiology to matched controls20. Mortality (10 percent versus 0) and major morbidity (24 versus 3 percent) were both significantly higher among patients with pulmonary hypertension. The increased risk warrants careful consideration of indications for surgery and discussion of potential risks with patients with pulmonary hypertension. HEART FAILURE The risk of pulmonary complications may be higher in patients with heart failure than in those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. This is suggested by data from the systematic review that formed the basis of the American College of Physicians guideline, in which the pooled adjusted odds ratio for pulmonary complications were 2.93 for heart failure patients and 2.36 for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease14. The original Goldman cardiac risk index has been shown to predict postoperative pulmonary as well as cardiac complications21. Although the Revised Cardiac Risk Index is now more commonly used to estimate risk for cardiovascular complications, validation studies of the revised index in predicting pulmonary complications have not been done. GENERAL HEALTH STATUS Overall health status is an important determinant of pulmonary risk. Functional dependence and impaired sensorium each increase postoperative pulmonary risk14. The commonly used American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification correlates well with pulmonary risk and is one of the most important predictors of pulmonary risk. The criteria for assigning ASA class include the presence of a systemic disease that affects activity or is a threat to life. Thus, patients with significant preexisting lung disease would be classified in a higher ASA class. ASA class >2 confers a 4.87 fold increase in risk 14. Poor exercise capacity also identifies patients at risk. The inability to exercise predicts 79% of pulmonary complications15. PROCEDURE RELATED RISK FACTORS SURGICAL SITE Surgical site is the single most important factor in predicting the overall risk of postoperative pulmonary complications. The incidence of complications is inversely related to the distance of the surgical incision from the diaphragm. Thus, the complication rate is significantly higher for thoracic and upper abdominal surgery than for lower abdominal and all other procedures15. In a systematic review of 83 univariate studies, complication rates for upper abdominal surgery, lower abdominal surgery, and esophagectomy were 19.7, 7.7, and 18.9 percent, respectively14. The higher rates of complications in upper versus lower abdominal surgery relate to the effect upon respiratory muscles and diaphragmatic function. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is associated with shorter recovery times, less postoperative pain, and less reduction in postoperative lung volumes. Its impact on pulmonary complication rates is less well established. While the decrease in postoperative pain might be expected to translate into lower pulmonary complication rates, few studies have evaluated clinically important pulmonary complications as an endpoint. In a pooled analysis of 12 studies of laparoscopic versus open colon cancer surgery, there was a nonsignificant trend towards reduced pulmonary complications14. DURATION OF SURGERY Surgical procedures lasting more than three to four hours are associated with a higher risk of pulmonary complications. As an example, a study of risk factors for postoperative pneumonia in 520 patients found an incidence of 8 percent for surgeries lasting less than two hours versus 40 percent for procedures lasting more than four hours. This observation suggests that, when available, a less ambitious, briefer procedure should be considered in a very high risk patient14, 15. TYPE OF ANESTHESIA There are conflicting data with regard to the pulmonary risk of spinal or epidural anesthesia when compared with general anesthesia. One study, as an example, found no difference in the rate of pulmonary complications between patients undergoing transurethral prostate surgery with spinal anesthesia and those undergoing general surgery with general anesthesia14. In contrast, an early retrospective study of 475 men with chronic lung disease undergoing general surgery revealed a 9 percent incidence of death in the general anesthesia group compared with no deaths in the spinal anesthesia group22. These findings have been subsequently supported by others, including a review of high risk patients that found that the rate of respiratory failure was significantly higher with general anesthesia than with epidural analgesia and light anesthesia. Subsequently, investigators conducted the largest systematic review of this literature to date23. The review evaluated the results of 141 trials that included 9559 patients. They reported a reduction in risk of pulmonary complications among patients receiving neuraxial blockade (either epidural or spinal anesthesia) with or without general anesthesia, when compared to those receiving general anesthesia alone. Patients receiving neuraxial blockade had an overall 39 percent reduction in the risk of pneumonia and a 59 percent decrease in the risk of respiratory depression. Based upon this comprehensive review, it appears likely that general anesthesia leads to a higher risk of clinically important pulmonary complications than do epidural or spinal anesthesia, although further studies are required to confirm this observation. Regional nerve block is associated with lower risk and should be considered when possible for high risk patients. As an example, an axillary block with conscious sedation could be used for an upper extremity procedure. TYPE OF NEUROMUSCULAR BLOCKADE Pancuronium, a long-acting neuromuscular blocker, leads to a higher incidence of postoperative residual neuromuscular blockade than do shorter acting agents and a higher incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications in those patients with residual neuromuscular blockade24. Residual neuromuscular blockade is also an important risk factor for critical respiratory events in the immediate postoperative period25. PREOPERATIVE CLINICAL EVALUATION A careful history taking and physical examination are the most important parts of preoperative pulmonary risk assessment. One should seek a history of exercise intolerance, chronic cough or unexplained dyspnoea. The physical examination may identify findings suggestive of unrecognized pulmonary disease. Among such findings, Decreased breath sound dullness to percussion wheezes rhonchi prolonged expiratory phase predict an increase in the risk of pulmonary complications15. PREOPERATIVE PULMONARY FUNCTION TESTING The value of routine preoperative pulmonary function testing remains controversial. There is consensus that all candidates for lung resection should undergo preoperative pulmonary function testing. Such testing should be performed selectively in patients undergoing other surgical procedures. We will subsequently divide the discussion into patients undergoing lung resection and those for other surgical procedures. LUNG RESECTION After determining the anatomic resectability of the disease, it needs to be decided whether the patient can withstand the planned procedure and can survive the loss of the resected lung. Initial evaluation Detailed medical history, including coexisting disease to ensure the optimal treatment of that disease. History should include functional capacity and the degree of limitation of activity. A history of smoking or COPD may lead to preoperative therapeutic interventions such as bronchodilators and/or steroids. This could lead to some degree of reversal of airway obstruction and easier weaning of the ventilator postoperatively. The physical examination should include an evaluation for signs of metastatic spread and the presence of cardiac failure and pulmonary hypertension. All of these might change the treatment mode and determine that the patient may not be a suitable surgical candidate. The pulmonary specific evaluation can be divided into three stages of tests that are performed in a graded manner to meet the cited goals and help risk-stratify the patients prior to the anticipated surgery Stage I assessment Spirometry: Spirometry is a simple, inexpensive, standardized and readily available test. Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), Forced vital capacity (FVC), Forced Expiratory Flow, mid expiratory phase (FEF25-75%) and Maximum voluntary ventilation (MVV) have been extensively studied. FVC reflects lung volume, while FEV 1 and FEF25-75% reflects airflow. MVV reflects muscle strength and correlates with postoperative morbidity. However, it is very dependent on patient effort. Of all these indexes, FEV 1 is regarded as being the best for predicting complications of lung resection in the initial assessment26. Diffusion Capacity Diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) reflects alveolar membrane integrity and pulmonary capillary blood flow in the patient’s lungs. The usefulness of DLCO in predicting postoperative complications following pulmonary resection has also been evaluated. Retrospective studies have reported that actual DLCO (as a percent of the predicted value) and predicted postoperative DLCO are the most important predictors of mortality and postoperative complications27, 28. Arterial Blood Gas Levels Arterial blood gas levels have not been extensively studied as predictor of postoperative complications. Hypercapnia (PCO2 >45 mmHg) in arterial blood has been a relative contraindication to lung resection as it indicates chronic respiratory failure. A few studies however did not find that a PCO2 > 45mmHg was predictive of postoperative complications26. To summarize, studies on pulmonary function testing in the preoperative evaluation for lung resection surgery indicate that the following criteria are predictive of increased postoperative complications and mortality For pneumonectomy: FEV1 MVV DLCO FEF25-75% < 2L or < 60% of predicted < 55% of predicted < 50% of predicted < 1.6L/s For lobectomy: < 1L < 40% of predicted < 50% of predicted < 0.6L/s For wedge resection : FEV1 DLCO FEV MVV DLCO FEF25-75% < 0.6L < 50% of predicted These studies suggest that if values more than required for pneumonectomy above are achieved, no further testing is indicated and that the patient is at low risk for postoperative complications26. The current guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians and the British Thoracic Society suggest that patients with a preoperative FEV1 in excess of 2 L (or >80 percent predicted) generally tolerate pneumonectomy, whereas those with a preoperative FEV1 greater than 1.5 L tolerate lobectomy. However, if there is either undue exertional dyspnea or coexistent interstitial lung disease, then measurement of DLCO should also be performed. Patients with preoperative results for FEV1 and DLCO that are both >80 percent predicted do not need further physiological testing29. They do however concede that most studies used as the basis of current guidelines were published prior to 1990, and supportive care and perioperative management have improved substantially since that time. This could result in an overly restrictive approach to surgical therapy. If the above requirements are not met, the patient needs further evaluation. Stage II assessment The next stage of assessment consists of tests that measure individual lung function. Quantitative ventilation-perfusion scan or Differential lung scan 133Xe is inhaled or 99Tc-labeled macro aggregates are injected IV. The uptake by the lung is measured by a gamma camera and computer. The percentage of radioactivity contributed by each lung correlates with the contribution to the function of that lung. Normally the right lung contributes 55% and the left lung 45% of lung function. Based on the measured radioactive uptake of the lung that will not be operated on, the predicted FEV1 of residual lung following surgery can be calculated. Patients, who undergo a differential lung scan in the course of their preoperative evaluation for lung resection, may be allowed to undergo surgery if: Predicted postoperative FEV1 Predicted postoperative DLCO > 40% of predicted > 40% of predicted Patients whom do not meet these criteria should undergo further evaluation before surgery can be undertaken. Patients with a predicted postoperative FEV1 <30 percent predicted are particularly singled out for their risk of perioperative death and cardiopulmonary complications; they should be counselled about non-standard surgical options and non-operative treatment modalities in preference to standard lung resection29. Other tests assessing differential lung function include bronchospirometry, lateral position testing and total unilateral pulmonary artery occlusion. These tests are invasive; all require specialized equipment and a high level of technical expertise for their performance26. They are no longer performed in the preoperative evaluation of patients who are awaiting lung resection. Stage III assessment Exercise testing stresses the entire cardiopulmonary and oxygen delivery system, and provides a good estimate of cardiopulmonary reserve. Heart rate, blood pressure, ECG and oxygen saturation is measured, as well as the measurement of exhaled gasses. The oxygen uptake (VO2); maximal VO2 (VO2max); carbon dioxide output and minute ventilation can be measured. The rate of oxygen uptake increases with exercise until a point at which a plateau is reached and a further increased in work does not result in a further increase in oxygen uptake. This is the VO2max. In patients with COPD, dyspnoea or fatigue often interrupts exercise before this plateau. The VO2 at this stage is called peak VO2. VO2max or peak VO2 indicates whether the patient has the reserve to counter the multiple physiologic stresses that accompany surgery. Two major types of exercise tests have been used in the preoperative evaluation of high risk patients being considered for lung resection surgery 1. Fixed exercise challenge, in which a sustained level of work is performed 2. Incremental exercise testing in which the work is sequentially increased to a desired end point. The maximal end point can be can be defined as exercise that is performed to a plateau at which further increase in work will not produce an increase in VO2. The sub-maximal end point can be defined as exercise performed short of achieving the plateau. Stair climbing: For many years, surgeons have utilized stair climbing as a preoperative screening tool. Though poorly standardized, this form of testing has been shown to identify patients at increased risk for lung resection. In a prospective series of 640 lobectomy and pneumonectomy candidates, attainment of a lower altitude (less than 12 meters) on a symptom-limited stair climbing test was associated with increased cardiopulmonary complications, mortality, and cost, compared with climbing to a higher altitude (22 meters) 30. A prospective series of 160 patients studied one day prior to lung resection found that those who were able to climb more than eight flights of stairs, at their own pace, were less likely to experience complications than those who could climb fewer than seven flights of stairs (6.5 versus 50 percent). Patients who climbed between seven and eight flights of stairs had an intermediate risk of complications (30 percent) 31. Integrated cardiopulmonary exercise testing: The most important measurement during cardiopulmonary exercise testing that correlates with postoperative complications is the level of work achieved, as measured by maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max); invasive hemodynamic measurements during exercise provide little additional useful data 30. An early report demonstrated no mortality in patients able to achieve a VO 2max in excess of 1 L/min, compared with 75 percent mortality in those with a VO2max below 1 L/min31. Expressing VO2max in terms of mL/kg per min, which takes into account the patient's body mass, may increase the predictive power of the test. The VO 2max can also be expressed as a percentage of the predicted value. Current guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians considers patients with VO2max <10 mL/kg per min, or those with VO2max <15 mL/kg per min and both predicted postoperative FEV1 and DLCO <40 percent predicted, to be at high risk for perioperative death and cardiopulmonary complications29. OTHER SURGERY Pulmonary function testing There is considerable debate regarding the role of preoperative pulmonary function testing for risk stratification. These tests simply confirm the clinical impression of disease severity in most cases, adding little to the clinical estimation of risk. There has also been concern that preoperative PFTs are overused and a source of wasted health care money32, 33. Two reasonable goals that could potentially justify the use of preoperative PFTs: Identification of a group of patients for whom the risk of the proposed surgery is not justified by the benefit. Identification of a subset of patients at higher risk for whom aggressive perioperative management is warranted. A number of measures of pulmonary function have been evaluated. Bedside spirometry is widely available, and measures of the forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) have been frequently reported. Early reviews suggested criteria for increased risk that included the following: FEV1 FVC FEV1/FVC ratio <70 % predicted <70 % predicted <65 % There is little support from the literature that either of these goals is routinely met other than for lung resection surgery. As an example, in a study of patients with severe chronic obstructive lung disease (FEV1 <50 %), preoperative PFTs did not predict the risk of pulmonary complications, whereas length of surgery, ASA class, and type of procedure were all significant predictors. Similarly, in a case control study of 164 patients undergoing abdominal surgery, no component of spirometry predicted pulmonary complications 34. A critical review of preoperative pulmonary function testing evaluated 14 studies that met strict methodologic criteria14. Spirometric values were significant risk predictors in three of four studies that used multivariable analysis. However, other factors conferred higher odds ratios for pulmonary complications than did abnormal spirometry in two of these studies: ASA class >3 and chronic mucous hypersecretion. Two well designed case-control studies have evaluated the benefit of PFTs as risk predictors. In a study of patients undergoing abdominal surgery, there was no difference in FEV1, FVC, or FEV1/FVC between patients who had a pulmonary complication and those who did not. In contrast, factors from the physical examination did predict risk 34. Recommendation: Based on a systematic review, a 2006 American College of Physicians guideline recommends that clinicians not use preoperative spirometry routinely for predicting the risk of postoperative pulmonary complications35. A reasonable approach to patient selection for preoperative pulmonary function testing follows: Obtain PFTs for patients with COPD or asthma if clinical evaluation cannot determine if the patient is at their best baseline and that airflow obstruction is optimally reduced. In this case, PFTs may identify patients who will benefit from more aggressive preoperative management. Obtain PFTs for patients with dyspnea or exercise intolerance that remains unexplained after clinical evaluation. In this case, the differential diagnosis may include cardiac disease or deconditioning. The results of PFTs may change preoperative management. PFTs should not be used as the primary factor to deny surgery PFTs should not be ordered routinely prior to abdominal surgery or other high risk surgeries Arterial blood gas analysis No data suggest that the finding of hypercapnia identifies high-risk patients who would not have otherwise been identified based upon established clinical risk factors. Several small case series have suggested a high risk of postoperative pulmonary complications among patients with a PaCO2 >45 mmHg, a finding usually seen only in patients with severe chronic obstructive lung disease. The risk associated with this degree of PaCO 2 elevation is not necessarily prohibitive, although it should lead to a reassessment of the indication for the proposed procedure and aggressive preoperative preparation. Hypoxemia has generally not been identified as a significant independent predictor of complications after adjustment for potential confounders. Current data do not support the use of preoperative arterial blood gas analyses to stratify risk for postoperative pulmonary complications. Chest radiographs Abnormal chest x-rays are seen with increasing frequency with age. However, chest x-rays add little to the clinical evaluation in identifying healthy patients at risk for perioperative complications. As an example, one study screened 905 surgical admissions for the presence of clinical factors that were thought to be risk factors for an abnormal preoperative chest xray36. These risk factors were age over 60 years or clinical findings consistent with cardiac or pulmonary disease. No risk factors were evident in 368 patients; of these, only one (0.3%) had an abnormal chest x-ray, which did not affect the surgery. On the other hand, 504 patients had identifiable risk factors; of these, 114 (22%) had significant abnormalities on preoperative chest x-ray. A meta-analysis of studies of routine preoperative chest x-rays demonstrated a low yield for abnormalities that actually change preoperative management 37. Of 14,390 preoperative xrays, there were only 140 unexpected abnormalities and only 14 cases where the chest x-ray was abnormal and influenced management. The available literature does not allow an evidence-based determination of which patient will benefit from a preoperative chest x-ray however, it is reasonable to obtain preoperative chest x-ray in patients with known cardiopulmonary disease and in those over age 50 years undergoing high risk surgical procedures, including upper abdominal, aortic, esophageal, and thoracic surgery. Exercise testing Exercise testing has been studied most extensively in preparation for lung resection surgery. There are no data to support its routine use in the evaluation of patients prior to general surgery. PULMONARY RISK INDICES Three recent studies have proposed pulmonary risk indices. Cardiopulmonary risk index A combined Cardiopulmonary Risk Index (CPRI) was proposed in a study of patients undergoing pulmonary resection based upon the Goldman criteria for cardiac risk 38. The pulmonary risk factors added to the cardiac risk index include the following: Obesity (BMI >27 kg/m2) Cigarette smoking within eight weeks of surgery Productive cough within five days of surgery Diffuse wheezing or rhonchi within five days of surgery FEV1/FVC <70% PaCO2 >45 mmHg The results of this scoring system have been mixed. Patients with a combined score greater than 4 (of a total of 10 possible points) in the original series were 17 times more likely to develop postoperative pulmonary complications than those with a score less than 4; no complications occurred in patients with a score of 2 or less. However, this study included only patients undergoing lung resection. A subsequent trial reported that, of 43 patients undergoing thoracic and upper abdominal surgery, the 8 with a CPRI >3 all experienced pulmonary complications39. In contrast, another review found that the CPRI did not predict complications in a cohort of 180 patients undergoing thoracic surgery40. In addition to the discrepancy between these studies, a limitation of this index is the requirement for PFTs and arterial blood gas analysis in all patients as part of the index. Brooks-Brunn risk index A separate study of 400 patients undergoing abdominal surgery identified a different set of proposed criteria for a risk index34. Six factors were independently associated with increased pulmonary risk after abdominal surgery: Age >60 Obesity (BMI >27 kg/m2) Impaired cognitive function History of cancer Smoking history in past eight weeks Upper abdominal incision In a subsequent validation cohort by the same author, the original model validated relatively well, but when a new model was developed different factors emerged as significant41. Multifactorial risk index for postoperative respiratory failure Using a prospective cohort model that included both derivation and validation cohorts from a large Veterans Administration database, investigators have more recently published the most ambitious multifactorial risk index to predict postoperative respiratory failure42. This index is modelled after the widely used cardiac risk indices. The authors evaluated those factors that predicted postoperative respiratory failure, assigned each points based on their strength in the multivariate analysis, and developed a risk score. Procedure-related risk factors dominate the index with type of surgery and emergency surgery being the most important predictors. New observations in this study included the importance of abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, emergency surgery, and metabolic factors as risk factors. The same investigators have also reported a similar index to predict postoperative pneumonia 43. These indices significantly advance the field of preoperative pulmonary risk assessment. They rely upon readily available clinical information. A limitation is that most of the factors are not modifiable. RISK REDUCTION STRATEGIES Preoperative Encourage cessation of cigarette smoking for at least 8 weeks Treat airflow obstruction in patients with COPD or asthma Administer antibiotics and delay surgery if respiratory infection is present Begin patient education regarding lung-expansion maneuvres Intra-operative Limit duration of surgery to less than 3 hours Use spinal or epidural anesthesia Avoid use of Pancuronium Use laparoscopic procedures when possible Substitute to less ambitious procedure for upper abdominal or thoracic surgery when possible Post operative Use deep-breathing exercises Use continuous positive airway pressure Use epidural analgesia Use intercostals nerve blocks15 SUMMARY Postoperative pulmonary complications are an important source of perioperative morbidity and mortality. They represent an extension of the normal physiologic changes in the lung that occur with anesthesia. A careful history and physical examination are the most important tools for preoperative risk assessment in evaluating patients for potential postoperative pulmonary complications. Attention should be paid to symptoms that suggest the possibility of occult underlying lung disease, including exercise intolerance, cough, and unexplained dyspnea In addition to the history and physical examination, a chest x-ray should be obtained in patients undergoing high risk surgery who are over age 50 years, or if cardiac or pulmonary disease is suggested by the clinical evaluation, unless one has been obtained in the past six months. Pulmonary function tests should be reserved for patients with uncharacterized dyspnea or exercise intolerance and for those with COPD or asthma where clinical evaluation cannot determine if airflow obstruction has been optimally reduced. The benefit of PFTs in other situations is unproved. There is no role for preoperative arterial blood gas analyses to identify high risk patients or to deny surgery.